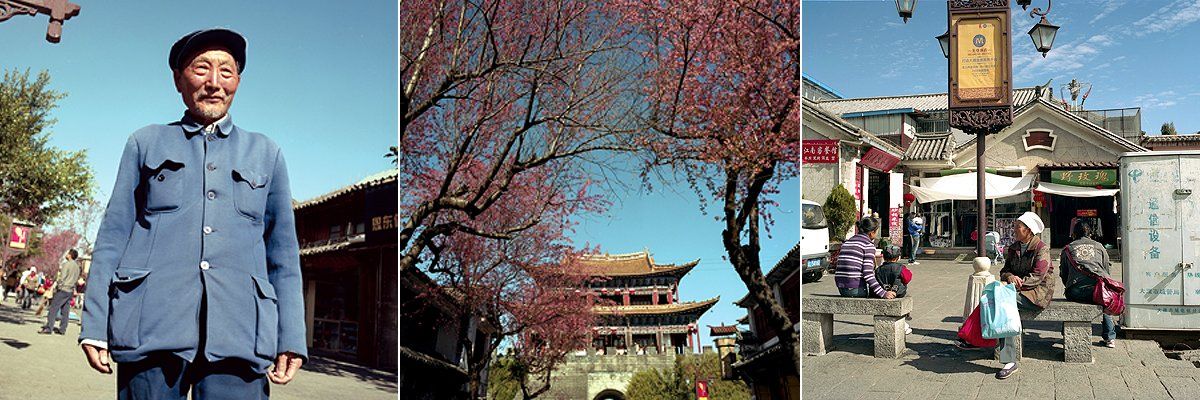

For the past two decades, the Old City of Dali in China's southwestern province of Yunnan—a picturesque burg with a temperate climate and auspicious feng shui—has been a destination for Chinese urbanites and Western travelers looking to escape the country's industrial grind. Starting in the 1990s, when more than a dozen well-known Chinese painters built studios here, cultural elites have migrated to Dali in hopes of it being the next Shangri-La—that fictional utopian valley hidden deep in the Himalayas in James Hilton's 1933 novel Lost Horizon.

"Dali isn't your average little city," says painter Han Xiangning, who has made Dali his home after living abroad for four decades in New York. Han's residence—a white minimalist compound with its own private lagoon—moonlights as a gallery featuring art by luminaries such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Zhang Xiaogang, and Fang Lijun. Because Dali tends to be so welcoming to outsiders, and because it's a bit of an ethnic melting pot, Han likens it to a "mini–New York City," albeit one perched on the banks of the idyllic Erhai Lake and framed by the snowcapped Cang mountains.

The city's inclusive nature may have something to do with the fact that Dali was once the capital of the independent Nanzhao Kingdom, which the Chinese empire conquered by force six centuries ago. The majority of people in the area are in the Bai ethnic minority, a Sino-Tibetan community famous for its artistic creativity. Part of the area's charm derives from its graceful buildings erected in the traditional Bai architectural style, with upturned roof gables evocative of Thai temples. The architecture enchanted American gallery owners Brian and Jeanee Linden, who opened a 14-room guesthouse and cultural center in a lovingly restored historic courtyard mansion about 18 kilometers outside the Old City. The Linden Centre's rooms are stocked with valuable Chinese antiques, and the hotel offers its own piece of paradise with morning tai chi sessions, a Zen meditation room, and a rooftop terrace with uninterrupted views of the mountains. "Here's where we found our dream," says Brian Linden, who sold the couple's home in the U.S. to bankroll the renovation.

The No. 1 reason American author Dan Reid has rented a house in Dali is its aura of old China. "It's the only place in all of China where I can still feel the slow, deep, rich pulse of traditional Chinese civilization," says Reid, who speaks, reads, and writes Chinese and has authored a number of books, including The Tao of Health, Sex, & Longevity. Reid also contends the city has the best produce he's found in Asia, because it "hasn't been terminally poisoned by Chinese industry, as the rest of the country has."

Clearly, other Western travelers feel similarly drawn to Dali's charms: the city has become such a magnet for foreign backpackers that the avenue once known as Protecting the Nation Street is today called Foreigners' Street, where one can sip cappuccinos and sample local delicacies such as fried cow cheese and goat curry. But Dali's rising popularity is creating a dilemma: how long can this modern Shangri-La remain a place to get away from it all?

Case in point: this year's Third Moon Festival, one of Dali's biggest events, which dates back to the eighth century. It's always been a raucous gathering, where 5,500 vendors converge to sell everything from vats of pickled vegetables to camel-wool quilts from Mongolia to a Tibetan herbal Viagra known as "caterpillar fungus." The cacophony associated with the Third Moon Festival has been unchanging for centuries. But this April, the chaos was magnified by numbers and technology. More than 228,000 tourists (mostly domestic) descended on the festival grounds. Vendors barked through battery-powered bullhorns, and individual stalls blared Chinese music through stereo speakers: the effect was a claustrophobic and earsplitting din.

Another issue for Dali is its reputation as a place to score drugs. Marijuana grows wild in this part of Yunnan, and Dali has been nicknamed the "Amsterdam of China" for the ease with which pot is sold and smoked. Such activities occasionally cause expats to run afoul of the law—in 2009 a Chinese court sentenced an American to three years in prison after Dali cops discovered 15 kilograms of marijuana and a drug lab at his house.

An influx of tourists may also soon lead to increased attention from authorities and real-estate developers, disturbing Dali's mellow aura. This scenario has befallen several Yunnan cities that tried to cash in on the allure of Shangri-La. One such place, the World Heritage Site of Lijiang, has seen so many original inhabitants forced out by rising rents and gentrification that the town now feels hollowed out. Another nearby city, Zhongdian, tried to make a quantum leap into prime-time tourism by actually renaming itself Shangri-La. But for many, the only captivating thing about the place was the name. One Wikipedia entry describes part of the Old Town as "endless shophouses selling tourist trinkets (including fake tiger skins and counterfeit North Face jackets), minority costumed dancers and too-clean streets."

By contrast, Dali has never explicitly claimed to be utopia—but this low-key lack of self-promotion is the very reason many fans find it a paradise. The question now is whether this laid-back enclave will become a victim of its own success.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.