Among China's greatest art treasures are the Buddhist caves near Dunhuang, a Gobi Desert oasis on the fabled Silk Road that once linked China and Europe. Their ancient frescoes, sculptures, and other relics date as far back as A.D. 430 and have survived wars, environmental damage, antiquities hunters, and the chaotic Cultural Revolution.

Today domestic tourism is the biggest threat: the UNESCO World Heritage site—which includes more than 700 caves, as well as 2,400 clay sculptures and 45,000 square meters of frescoes—has an optimal capacity of 3,000 per day, but peak times can see twice that many visitors.

The caves, also known as the Mogao Grottoes, are especially vulnerable to mass tourism. Their ecosystems are fragile, and a buildup of humidity and carbon dioxide—from visitors' breath—can lead to flaking and discoloration of the delicate pigment-on-plaster wall paintings.

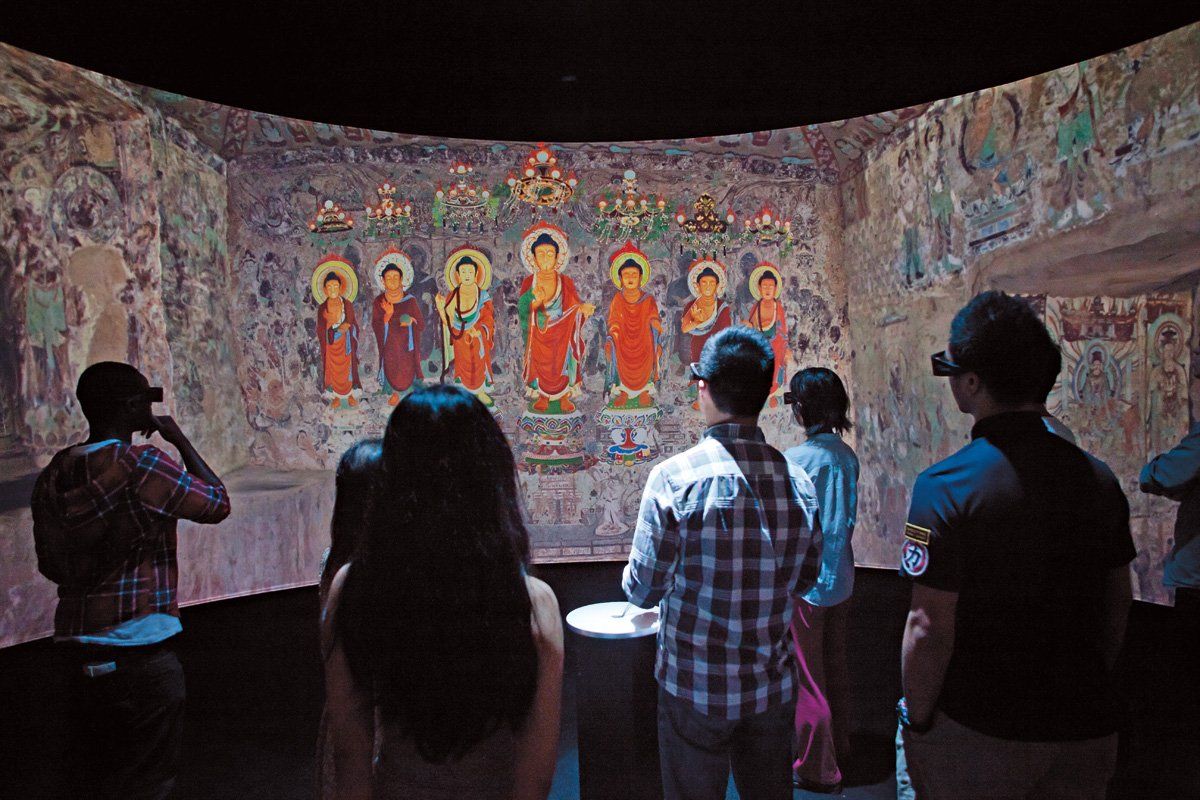

In a bid to preserve the caves, the Dunhuang Academy is pioneering an ambitious project to digitize the site. Recently, the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C., offered a tantalizing glimpse at the undertaking. Donning 3-D glasses, visitors were transported into a breathtaking "virtual" Dunhuang grotto, known as Cave 220, which boasts early Tang paintings from around A.D. 642. The 3-D, interactive experience is flooded with vivid color, close-up details, moving images of flying bodhisattvas riding mythical animals, even sound. "Not only does Dunhuang rank as the single most important repository of early Chinese art, but it is also here that the great cultures of the world—Greek and Roman, Persian and Middle Eastern, Indian and Chinese—constantly interacted for over a millennium," said Mimi Gates, who formed the Dunhuang Foundation to help preserve the site. "High-resolution digitization will provide a lasting record of this artistic treasure for all mankind and [can] make the site widely accessible inside and outside of China."

More than a dozen years ago, the Dunhuang Academy—which conducts research into and raises public awareness of the grottoes and their relics—began cooperating with foreign institutions to conserve the treasures. Among the projects, one used a camera with a billion-pixel resolution to create a digital archive of the caves. The results will be used in the academy's planned $40 million state-of-the-art visitor center—slated for completion next year—which will present virtual tours of the caves to save the real site wear and tear. The scope of the project is daunting. It requires 20 minutes or so to record a 9-square-meter fresco, and there are 492 caves with murals inside. But the Sackler exhibit proved how enthralling even a single virtual cave can be.

In the real caves, there are no lightbulbs (too damaging), and once a cave reaches critical levels of moisture and temperature, it is shut to the public. Only a few dozen caves are accessible to visitors at any given time. By contrast, the Sackler's virtual tour was up close and personal. One of the most popular features was the "magnifying glass," which can zoom in on, say, a zither depicted in a mural. The instrument appears to pop out of the wall, enlarge, and then rotate in space as harp-like Tang- dynasty zither music plays on the audio track. Visitors can also "flip" back and forth between the intricate Tang-dynasty mural and a later, cruder Sung-dynasty fresco, which hid the original painting until 1943.

To help Cave 220's Tang dancer paintings magically come to life, two Chinese performers were flown to the Applied Laboratory for Interactive Visualization and Embodiment (ALiVE) at the City University of Hong Kong, which conceived and designed the interactive tour. For three days the dancers were filmed over and over performing intricate steps, fluid movements, and careful manipulation of long, sinuous ribbons. They appeared in the Sackler tour, dancing as if in midair, clad in brightly colored Tang period costume. ALiVE's project manager, Leith Chan, said that while he's become intimately familiar with the images of Cave 220, he hasn't been to Dunhuang yet. "I can't wait to visit the real thing."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.