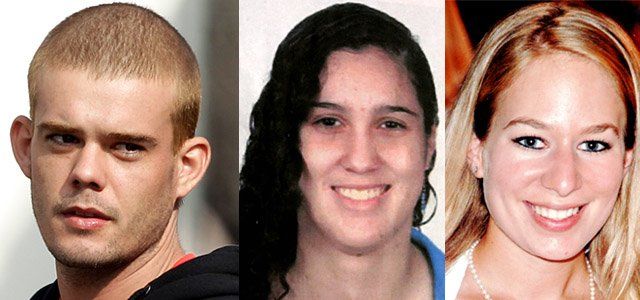

If there are rules of behavior for people suspected of heinous crimes, no one told Joran van der Sloot. The 22-year-old Dutchman was arrested Thursday in Chile in connection with the murder of a girl in Peru. But he'd been drawing plenty of attention to himself even before that: he was arrested and released twice in connection with the 2005 disappearance of Alabama teenager Natalee Holloway while she was on a school trip to Aruba. A failure by authorities to find the body may have kept him from being convicted, but it didn't keep his mouth shut: van der Sloot, the last person to be seen with Holloway, has told various stories about that night, and he was even caught by hidden camera confessing to having dumped her at sea. So the last thing van der Sloot should have had in his Peru hotel is the corpse of another young woman. But that is exactly what police in Lima, Peru, say they found on June 1—the bloodied body of 22-year-old Stephany Flores Ramirez, the daughter of a former race-car driver and local businessman. Afterward, van der Sloot slipped into Chile, which is where he was busted.

The mystery, though, isn't about whether he committed these crimes—circumstantial evidence notwithstanding, it's conceivable he could be innocent, and a jury never found him guilty. The mystery is why kids like van der Sloot act like a perp at every turn, despite being tracked by the limelight everywhere they go. During the five years since Holloway's disappearance—eerily on the same date of Ramirez's murder—van der Sloot has reveled in sick infamy as the prime suspect in an unsolved mystery. Shouldn't he have kept his head down?

He's not alone. Stories like van der Sloot's are increasingly common among the current post-teen generation that grew up on reality television and virtual realism. Think of suspected child-killer Casey Anthony and the study-abroad student-murderer Amanda Knox, for instance. Kids in big trouble share the same sense of life without consequences—and an obvious loss of their moral compass—when it comes to the gravity of the accusations against them. It's as if they've been conditioned to believe that life can simply be reset like a video game if things start to go bad. Or maybe that fame—even infamy—is so intoxicating that they just want more.

Florida resident Casey Anthony was 22 when her 2-year-old daughter, Caylee, went missing. Like van der Sloot, Casey told authorities multiple versions of the events surrounding her daughter's disappearance. She first blamed a woman she claimed was her babysitter, though the two had never met (she admitted that she took her name out of the phone book). Her conflicting stories were compounded by her strangely pretentious behavior before she was an official suspect. Not only had she waited a month to report her toddler's disappearance, she spent that month partying with friends. Even after she became a suspect in the case, in which she maintains her innocence, she was photographed living it up at Orlando nightclubs. When Caylee's decaying body was finally found with the skull wrapped in duct tape, Casey was arrested for first-degree murder and is currently awaiting trial. Only then did she seem to understand the magnitude of the allegations against her.

Certainly no one is more famous as an irreverent celebrity suspect than Seattle native Amanda Knox, who is serving a 26-year sentence for the sexual assault and murder of her British roommate, Meredith Kercher, in Perugia, Italy. In the early days of the Kercher murder investigation, Knox and her former boyfriend, Raffaele Sollecito, acted absurdly. Knox, with no apparent grasp of the seriousness of a murder investigation, performed cartwheels for the cops in the police station waiting room. The two suspects admitted to being high before talking to police, as Sollecito said, "to take the edge off." They told investigators multiple stories and lies, including Knox's naming her Congolese nightclub boss as the real assassin. For added flavor, she even described Kercher's screams to investigators. During her 11-month trial, she behaved like a beauty queen on the runway, making what jurors later called a mockery of the court by her blatant disrespect of the Italian legal system. In the final days of her trial, when things were looking grim, she started to act demure. By then it was too late.

For his part, van der Sloot's escapades are well chronicled, particularly by the Dutch tabloids. He has posed nude for an online porn site, and European broadcasters have complained that he often demands payment for his television appearances—especially when he confesses—about the Holloway case. During a recent trip to Thailand he hinted that he wouldn't mind getting into the business of sex trafficking and even joked that he'd sold Holloway as a sex slave. He was in Lima to take part in an international poker tournament known for its drug climate.

His friends in Holland and Aruba say his reputation is one of arrogance and self-entitlement. When Peter R. de Vries, one of Holland's toughest crime reporters (picture the male Greta Van Susteren) questioned him on a television program about Holloway's murder, his response was to throw a glass of wine in the journalist's face the moment the show ended. "This says something about Joran," de Vries said after the broadcast. "He doesn't have complete control over his behavior."

With Anthony and Knox, their actions greatly affected how people—and, inevitably, juries—perceived their guilt. A judge on Anthony's case was removed for corresponding with a blogger who had chronicled the details of Caylee's murder. And Knox's prosecutors in Perugia admitted to scouting for juicy details about her on blogs, where they hoped people would post salacious information they could use to their advantage. The court of public opinion can still reach into the court of law. New York lawyer Joseph Tacopina, who consulted Knox's defense and represented van der Sloot in the Holloway case in Aruba, maintains that both are victims of bad press, but admits the prejudice is largely fed by their own actions. "In both instances, the sensationalism far outweighed the facts of the cases," he told NEWSWEEK.

Van der Sloot's troubles must feel like a recurring nightmare by now. He had walked away from the Holloway incident scot free, despite a mound of circumstantial evidence and his own multiple confessions. His father was an influential judge in Aruba, which may have helped him stay out of jail. But his father died last year, and he was arrested Thursday on an international warrant. Tacopina, who has not heard from van der Sloot, says that even if he is implicated in the Lima case, that does not "create" evidence in Aruba. Fair enough, but van der Sloot has probably also realized that, after acting like a reality-TV star rather than a murder suspect in Aruba, the show is finally over.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.