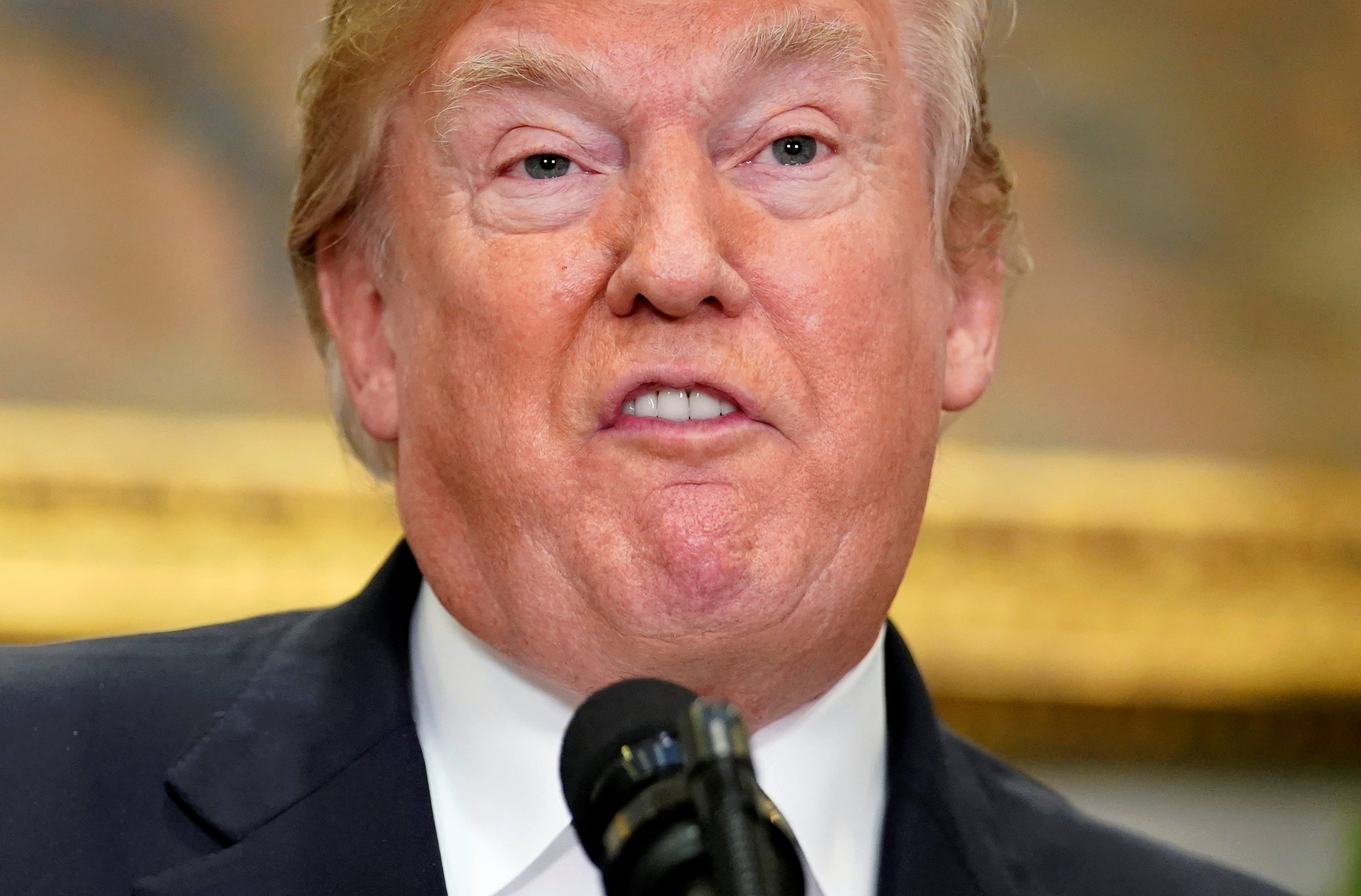

In the first 167 years of its publication, The New York Times used the term "fake news" about 320 times, mostly in relation to The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and other television programs that did fake news, and did it funny. Then, in the last several years, there were reports of misinformation, i.e. fake news, being spread by hostile nations, which was not especially funny. Then came the election of Donald Trump, and nothing was funny anymore, and least not to the kinds of people who read The New York Times and watch The Daily Show.

In the two-and-a-half years since Trump announced his candidacy for the White House, the newspaper has deployed the phrase on some 1,150 occasions, often in reference to him. The Times has also kept a running list of his lies, titled simply "Trump's Lies."

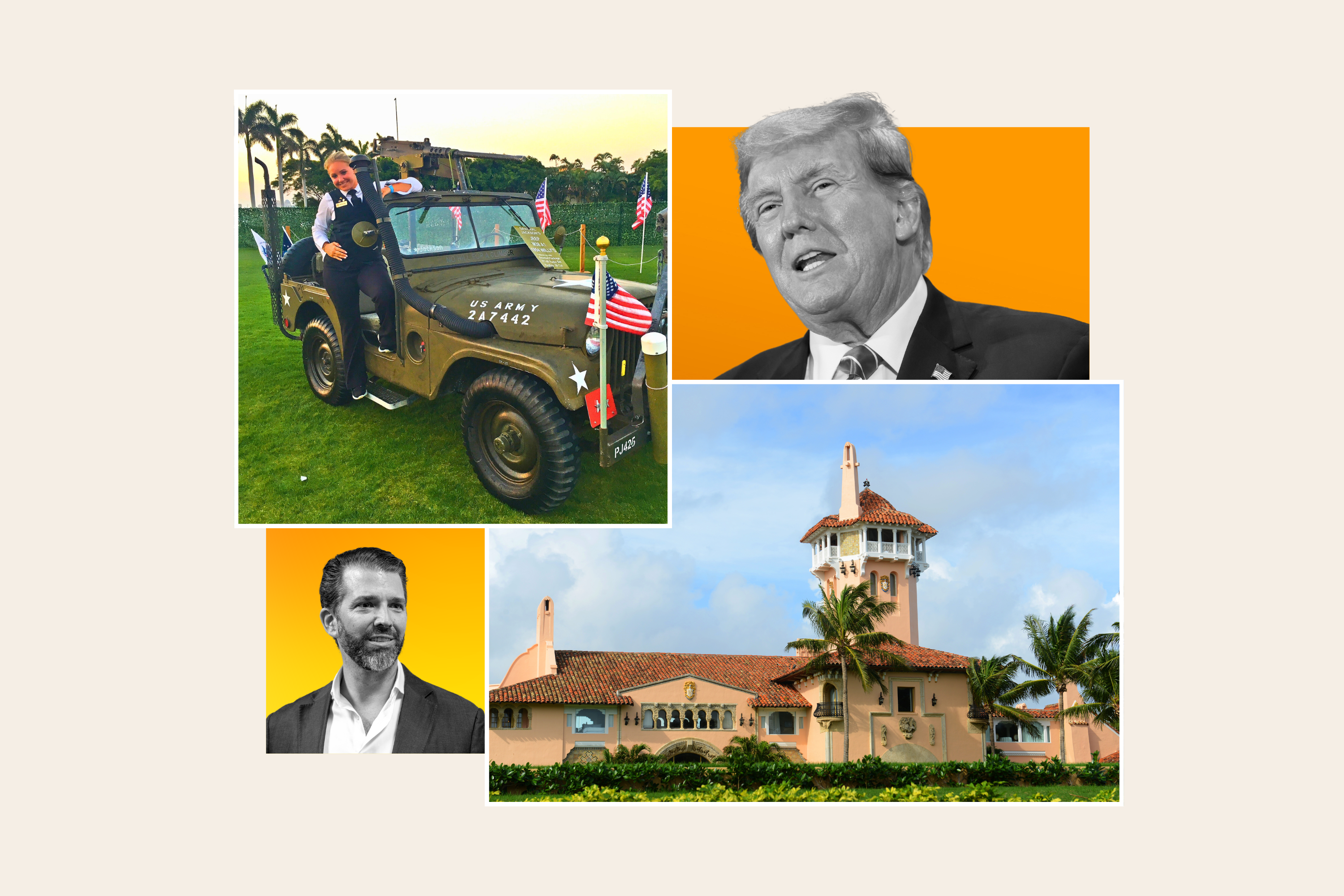

Now, in the run-up to the one-year anniversary of his inauguration, come Trump's "Fake News Awards," slated for Wednesday, a culmination of his unprecedented campaign against a media establishment he sees as united against him. By constantly seeking to discredit news reports and routinely making accusations of bias, he has forced journalists into a defensive crouch like no chief executive before him.

The Fake News Awards, those going to the most corrupt & biased of the Mainstream Media, will be presented to the losers on Wednesday, January 17th, rather than this coming Monday. The interest in, and importance of, these awards is far greater than anyone could have anticipated!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 7, 2018

Every president has had his gripes with the press; none, before Trump, has declared outright war. And it is a war he is winning: a Knight Foundation study published this week finds that only 44 percent of Americans "say they can think of a news source that reports the news objectively."

Whether or not Trump invented the term "fake news" or not—he claims he did, though there are competing claims—it has infiltrated our lives, supplanting Stephen Colbert's "truthiness" as the epithet that best symbolizes our chaotic media landscape, in which conspiracy theories vie for attention with investigative reports, in between volleys of always-controversial presidential tweets. "A year into Donald Trump's fact-bending, media-bashing presidency," the Associated Press reported on Monday, "Americans are increasingly confused about who can be trusted to tell them reliably what their government and their commander in chief are doing."

Trump remains the man he has always been, a creature of the Manhattan media, at once loved and loathed by newsrooms full of ambitious Ivy Leaguers who would never wear a Trump-brand tie. And while many journalists may sneer at his politics, they know that his presidency has driven people to consume the news like no political development in recent memory.

Most everyone who reports on Trump understands that his attacks have a theatrical, over-the-top quality that renders them not all that different from the real estate mogul's cameos at professional wrestling events. It is not clear, however, that all of Trump's fans understand as much. During the campaign, rallies would break out into taunts of "Lügenpresse," the lying press, a term used by the Nazis. At one rally, a man showed up in a t-shirt that read: "Tree. Rope. Journalist. Some assembly required." The t-shirt was even briefly sold at Walmart, though it was pulled after a social media outcry.

"Rope. Tree. Journalist." shirt spotted at @realDonaldTrump rally in MN _ Reuters photo by Jonathan Ernst pic.twitter.com/1VTkYPOOVo

— Michael Biesecker (@mbieseck) November 7, 2016

Despite all this, it's inarguable that Trump has elevated the press by demonizing it. "Fundamentally, Trump has been fantastic for the U.S. media," says Joel Simon, head of the Committee to Protect Journalists, which chronicles oppression of press freedoms around the world.

Simon notes that President Barack Obama's White House "marginalized" journalists, carefully doling out access while diligently plumbing leaks. This one seems to speak to them freely. "Michael Wolff waltzes into the White House and no one seems to notice. Believe me that wouldn't have happened during the Obama administration," Simon says laughingly in reference to the Fire and Fury author who was, fittingly, earlier known as a scavenger of Manhattan media gossip.

At the same time, some can't help but see authoritarian impulses in Trump's dealings with the press. According to prepared remarks from a speech he is set to give Wednesday, Senator Jeff Flake, Republican of Arizona, is to say, "it is a testament to the condition of our democracy that our own president uses words infamously spoken by Joseph Stalin to describe his enemies," in reference to Trump's branding of the press as the "enemy of the people" last year. Flake has clarified that he does not believe that Trump is similar to Stalin.

Simon of CJP says he's most concerned about Trump's signals to dictators around the world. "Authoritarian leaders feel like they have this great new framework in 'fake news,'" Simon says. In response to Trump's announcement that he would present fake news awards, CPJ awarded him for "Overall Achievement in Undermining Global Press Freedom." The award may have been a joke, but CPJ's argument was not, charging that Trump "consistently undermined domestic news outlets and declined to publicly raise freedom of the press with repressive leaders."

"He's definitely followed the authoritarian playbook," says Ruth Ben-Ghiat, a historian of dictatorships at New York University. In doing so, she says, he has also given democracy-averse leaders around the world a playbook of his own, showing them how to wield the weapon that is "fake news." In December, The New York Times reported that "many of the world's autocrats and dictators are taking a shine to" fake news, including Venezuela's socialist leader, Nicolás Maduro, and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

"If you can take down American democracy—it clearly encourages them to act worse," says Ben-Ghiat.

For Trump supporters, however, the president is not so much "taking down" democracy as taking down the press, which they have long viewed with suspicion. A new study says that 42 percent of Republicans brand negative stories as "fake news." Trump has taught them that the media is a malevolent, even anti-American entity, singularly determined to undermine his presidency.

"I think he has a real enmity for those he believes are not telling the truth about him or his administration," says longtime adviser Roger Stone. The attacks are "right out of the Nixon playbook," says Stone, who got his start in politics working for the Nixon presidential campaign in 1972.

Like most in Trump's inner circle—including the president himself—Stone displays an immensely detailed knowledge of the media. He says, for example, that The New York Times is "basically balanced," while CNN is "a propaganda arm" of the liberal establishment.

"It's the free-for-all that the U.S. Constitution guarantees," Stone says nonchalantly when I bring up complaints about Trump's dealings with the press. Trump clearly agrees, as his "Fake News Awards" show. In a frequently tumultuous first year of his presidency, he has rarely wavered from a desire to frustrate the press by calling into question its every motivation. At the same time, he remains intent on being at the center of every news cycle. That has kept the media busy, as energized by the battle as the Oval Office adversary.

Subscriptions to newspapers and magazines are soaring, as upbeat press releases from The New York Times and The Washington Post indicate. People are watching cable news. Journalists are celebrities. Reporters are heroes—or, as Trump sees them, villains.

"He cares a lot about what you do and say," Simon reminds journalists writing about Trump, who are daily faced with a complex deluge of information coming from Washington. "So you have influence."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Alexander Nazaryan is a senior writer at Newsweek covering national affairs.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.