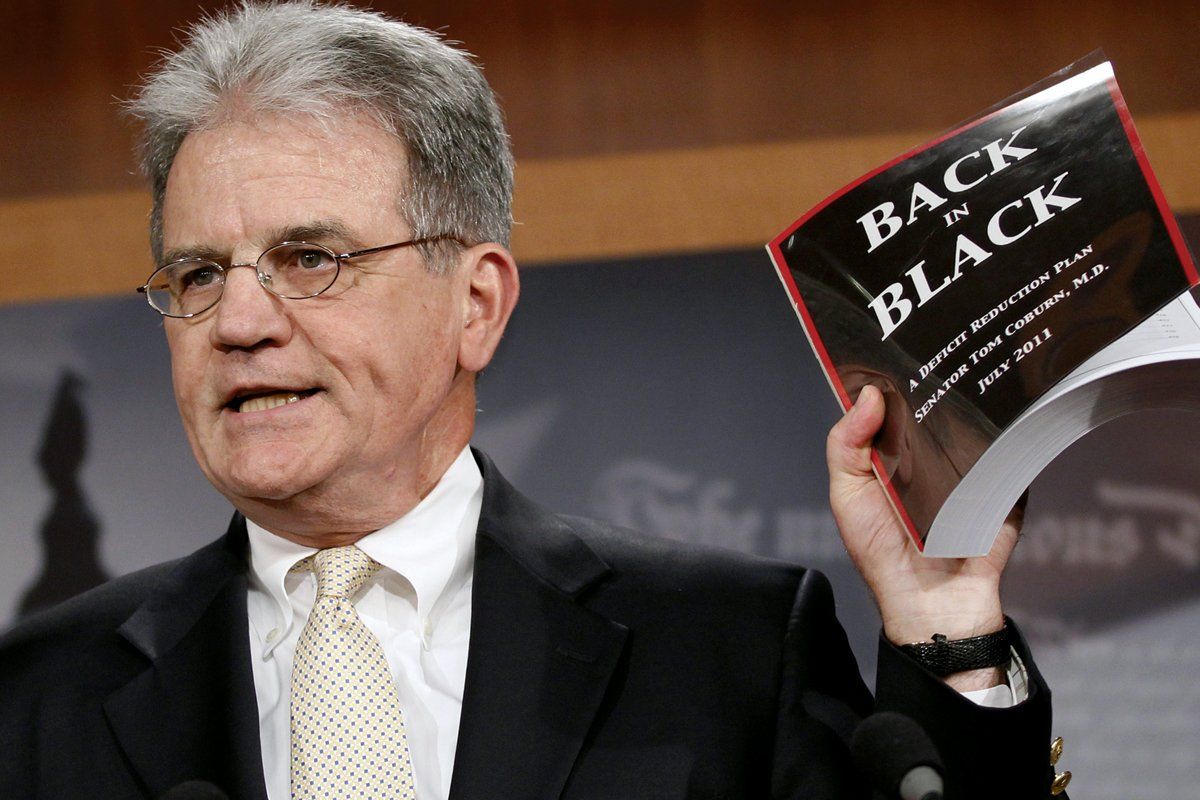

For a moment, the political warfare over the debt crisis seemed to pause, and standing there bearing the flag of compromise was a most surprising figure—Republican Sen. Tom Coburn of Oklahoma, whose reputation as a radical fiscal hawk and obstructionist had earned him the nickname "Dr. No."

Coburn, who has spent his political career happily unfazed by the prospect of unpopularity, suddenly found himself declared the man of the hour by those rooting for a deal when he rejoined the Senate's bipartisan Gang of Six, endorsing a blueprint for a potential way out of the debt impasse.

"The hard right says I'm a RINO now," Coburn says, referring to the term—Republican in Name Only—derisively applied to those who betray conservative orthodoxy. Indeed, the conservative reaction was swift, and fierce. Rush Limbaugh said that compromise such as Coburn's was a fool's game, practiced by Republicans with "spines of linguine."

Back home in Oklahoma, a local Tea Party group organized a protest against Coburn, and some national Tea Party leaders pronounced withering rebukes. "His reputation is as being pretty strong fiscally, but then when he joined the Gang of Six and this nonsense about adding a trillion dollars in the middle of either a depression or a recession—that is just lunacy," said Judson Phillips, founder of Tea Party Nation. Matt Kibbe, president of Freedom Works, declared himself baffled by Coburn's move. "I think Senator Coburn knows better," he said.

The Tea Party critique was almost amusing, given Coburn's history as a spiritual godfather of the movement.

In the autumn of 2005, before he'd been in the Senate a year, Coburn took to the floor of the chamber and did something that freshmen senators did not do—he delivered a speech roundly critical of a senior Republican colleague's pet project. The senator was Ted Stevens of Alaska, and the project was a $233 million earmark for "the bridge to nowhere"—the very symbol of wasteful pork spending.

That speech helped to galvanize anti-earmark sentiment inside Congress and beyond. Coburn supported the fledgling "Porkbusters" movement, popularized by University of Tennessee law professor Glenn Harlan Reynolds, the blogger known as Instapundit. Reynolds believed in the persuasive power of ridicule, and Coburn helped to provide the movement with the ideal weapon—a law pulling the curtain back on who was stuffing pork into which legislation. "Coburn was very involved in the embryo of the Tea Party movement, the Porkbusters movement," says Reynolds. "I would say that Coburn was Tea Party before there was a Tea Party."

Coburn says that he deeply admires the movement ("I think the Tea Party is one of the best things that ever happened to this country"), but he has not publicly associated himself with it, as some, such as Jim DeMint and Michele Bachmann, have. This is partly because Coburn believes that politicians tend to exploit such forces, but it is also because Coburn's natural role is as a dissident, rather than a move-ment leader.

Coburn arrived in Washington with a distinct political advantage—a willingness to leave. He'd survived a youthful encounter with cancer, which, he later said, drastically altered his perspective. He quit business to study medicine, and, in 1994, he put aside his medical practice in Muskogee, where he was a deacon in his Southern Baptist church, to join the Gingrich revolution. Gingrich promised an early vote on term limits if Republicans took the House, and when Republicans won, the vote was taken—but, to Coburn's dismay, the term-limit proposal was rigged to fail. Republican leaders, accustoming themselves to power, employed a gambit called "Queen of the Hill," whereby several term-limit measures were proposed, giving members a chance to vote for the reform, without fearing that any one of the proposals would actually pass.

Coburn made his own term-limit pledge, kept to it, and in 2001, after six years in the House, he left and wrote a book about Washington ways called Breach of Trust. When he ran for the Senate three years later, it was again with the promise to term-limit himself, vowing to return to Oklahoma when his current term ends in 2016. This has given him license to follow his own way, with a degree of certainty in the rightness of his positions that his colleagues, on both sides of the aisle, have often found grating. He has used a mastery of Senate rules to become a one-man bottleneck on legislation that, in his view, squandered taxpayer money, placing "holds" on measures that his colleagues deemed bulletproof—such as a move to commemorate "The Star Spangled Banner."

When Coburn came to Washington, he left his family behind in Muskogee. He opted to bunk with a group of colleagues, mostly conservative Chris-tians such as himself, in a house on C Street, a few hundred paces from the Capitol, partly to avoid the temptation of going native. As it happened, scandal came to the C Street house, in 2009, when one of Coburn's housemates, Sen. John Ensign, of Nevada, confessed to an affair with a staffer's wife. (Coburn had known of the affair for more than a year, and had tried to manage a private peace.)

Coburn's Gang of Six role—he left in May only to return—has put him at political variance with another C Street housemate, Senator DeMint of South Carolina, who believes that the Gang's rollout played into Obama's hands, and deflected attention from the House's "Cut, Cap, and Balance" legislation. "Jim may be right, and I may be wrong," Coburn allows. But he adds that political reality, not the Gang of Six, doomed the House proposal—which Coburn also supported. "I don't see a time anywhere in the future where there's 60 people that'll be in the Senate that think the way that Jim DeMint and I do."

Coburn suggests a hint of unease about his emergence as the key compromiser in the debt debate, especially in its timing. The Gang of Six rollout not only stepped on the House Republicans' plan, but provided political cover for Obama as his talks with House Speaker John Boehner broke down late last week. (Obama, who'd praised the Gang's proposal, said that his own bargaining position asked for even smaller revenue increases than the Gang's—and was therefore quite reasonable.)

Coburn says that he sympathizes with those conservatives, such as Sarah Palin, who insist that, if debt is the problem, raising the debt limit can't be part of the solution ("Intellectually, they are right"), and he sees his younger self in the hardline Tea Party caucus in the House.

But he also became convinced that the moment is truly dire. He thinks that America's credit rating will be downgraded, and says that it may serve his fellow politicians right. "That may be what it's going to take to wake up these guys, to make them realize you've got to make the hard choices," he said. "We've never been in this territory before. I mean, if we handle this wrong, we're near the end of our republic as we know it."

Still, he would not wish to have his new admirers believing that the former Tom Coburn, who resided on the fringe of the hard right, has disappeared. "Oh," he assures any doubters, "I am still on the fringe."

With David A. Graham

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.