Stephen Sondheim, American musical theater's most trailblazing composer, has just published the second volume of his collected lyrics, Look, I Made a Hat, which includes all the musicals since 1981 (the Pulitzer Prize–winning Sunday in the Park With George, Into the Woods, Assassins, Passion, and Road Show) as well as songs for television, movies, and special occasions. Like the first volume, Finishing the Hat, this one includes Sondheim's copious annotations, which wonderfully illuminate the songwriter's craft.

Craft? Not art? We'll get to the art. For now, craft is enough, because goodness knows there's enough of it in Look, I Made a Hat. (The titles of both books, for those who came in late, come from the lyric "Finishing the Hat," from Sunday in the Park With George. The song is about making art. "Look, I made a hat" is the song's penultimate line. The kicker is the last line: "Where there never was a hat.") Seen on the page, stripped of music, the lyrics can be seen for what they are: lines assembled—mortised is more like it—with grace and wit that is almost never obtrusive. Sometimes they're clever, sometimes they're funny, but never in the obtrusive way of a Cole Porter lyric. Sondheim's words serve Sondheim's songs, which in their turn serve the musicals of which they are a part.

This is craftsmanship of a very high order, but craftsmanship it is, because you can parse it, take it apart like a fine watch and see how it all fits together. Where the craft turns into art is in moments such as the second act of Sunday in the Park With George, where slowly and subtly a musical that has been delighting your brain suddenly turns your heart upside down. How exactly Sondheim and his librettist James Lapine achieve this transformation is not obvious. But that's where the art comes in.

Sometimes the art comes in more obviously. In Act II of Into the Woods, the Baker's Wife has a tryst with Cinderella's Prince, an experience that leaves her meditating on the either/or-ness of experience: "Must it all be either less or more,/ Either plain or grand?/ Is it always 'or'?/ Is it never 'and'? … Oh, if life were made of moments,/ Even now and then a bad one--!/ But if life were only moments,/ Then you'd never know you'd had one. … Let the moment go./ Don't forget it for a moment, though./ Just remembering you had an 'and,' when you're back to 'or,' / Makes the 'or' mean more than it did before."

Moments like that go by so fast in the theater that you might easily miss them, which makes Look, I Made a Hat all the more valuable. This book, together with its predecessor, provide a beautiful master class not only on Sondheim's work but on the act of songwriting generally. The text is, naturally, always articulate and illuminating. But it also shows us a side of Sondheim not so frequently seen—the always generous and grateful collaborator, as in this passage about working with his frequent librettist Lapine:

"When I think of songs like 'Sunday' or 'Move On' or 'No One Is Alone' [from Into the Woods], I realize that by having to express the straightforward, unembarrassed goodness of James's characters I discovered the Hammerstein in myself—and I was the better for it."

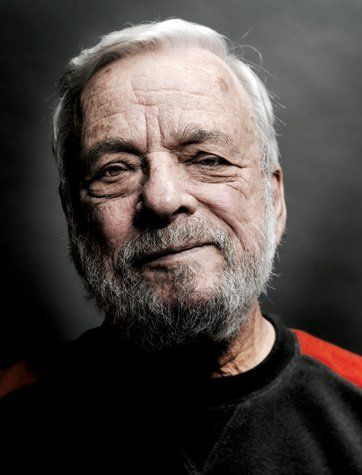

Sprawled on a sofa in his Manhattan townhouse, attired in T-shirt, gray slacks, and maroon slippers, Sondheim spent an hour last week discussing his work.

All the songs in both books are written for shows or for specific occasions, like someone's birthday. Have you ever written a song merely for the pleasure of writing a song?

I never did. Maybe I did when I was in my teens. But no, it never occurs to me to write a song just for the pleasure of writing a song. It has to be an assignment.

You cite the poet Paul Valery's notion that no poem is finished, merely abandoned. Throughout these books there's the sense that you don't see your work as fixed or static but fluid, even years later.

Absolutely. I think most theater work is like that. I would be surprised if Tennessee Williams didn't feel that way. Or anybody who deals in presentational art. I can't think of any playwright who would say, no, that play is perfect, I can't change a thing.

Are there some works of yours, though, that you feel are more fixed?

Yes, as I say in the second book, that's what I think about Assassins. That's the one that comes closest. There's so little that I want to fix there in my own work and nothing that I want to fix on [librettist] John Weidman's level. He may feel differently, but as far as I'm concerned his work there is unimprovable.

Road Show has had a bumpy history, including four title changes, different plots and characters and many changes to the score, and all of it included in this book. It's sort of gutsy to show all your false starts like that.

In a sense, I thought to myself, that section justifies the second volume—to take someone who cares about this subject and really walk them through the whole tunnel. That's a wonderful example of the difficulties and vicissitudes and mistakes and the triumphs of writing a show. And finally the boat comes into dock, and you say, yeah, that's what we wanted.

Over the course of your career, the subject matter ranges from ancient Rome to fairy tales to presidential assassins. Do you have a phobia of repeating yourself?

There are foxes and there are hedgehogs, and I'm someone who likes to go from subject to subject and know a little about a lot of things instead of a lot about one thing, so yeah, as soon as I feel myself repeating myself, I get worried.

Are there things you like about the current state of theater?

I don't really talk about the current theater. I never take an overview. Because it changes quickly and also I think it's a fool's game. I see some shows I like and some I don't. Generally I prefer plays to musicals, on both sides of the ocean. There aren't a lot of interesting musicals.

It seems that subsidized performing arts are where the good stuff is these days, whether it's musical theater or opera or…

Absolutely correct. Subsidized art is the answer. Non-profit theater is the only kind of theater that can afford to take the kinds of chances we're talking about. And musicals are still so expensive, so if nonprofits do musicals, they have to do small productions, things like Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson and Spring Awakening. They have to be smallish casts with smallish orchestras and smallish productions. You can't do Follies at a nonprofit, if you had the idea of writing Follies. There are cut-down versions of Follies, but that's not what was intended. You can do Assassins, or Sunday in the Park With George.

Do a lot of school drama groups do Assassins?

A lot. You're absolutely correct. There's nothing like antiauthoritarian subject matter. They do it a great deal. Also in Europe. See, America's a violent place. See, Americans kill their presidents.

For those of us who have always wondered where the composer leaves off and the orchestrator begins, how far do you take a score before the orchestrator takes over, and what directions do you give the orchestrator?

I do a very complete piano score before the orchestrator even sees it, because I was trained classically. I never give instructions to an orchestrator. What I do is play the score for them and they tape it. Jonathan Tunick, the orchestrator I've worked with most, gets a great deal from the way I play the songs, and that suggests to him various combinations of textures and timbres. Then he tells me what he thinks the makeup of the orchestra ought to be, and we discuss it. I don't have very many strong opinions. Sometimes I'll make a suggestion, but I don't know enough about orchestration to want to intrude.

So you don't say, "I hear strings here, winds there"?

Occasionally I do, very rarely. I did a film score once for an Alain Resnais movie, Stavisky, and at one point I told Jonathan, I think this cue should be all strings. And he said OK, fine, and then later when I heard it, it didn't sound very good. And I asked him, why did you go ahead with that? Were you just being nice to me? And he said, no, if we'd had 36 strings, it would have sounded great. With 12, not so great.

On the commentary track to the DVD of Passion, you say, in response to the preview audiences that giggled at the desperate Fosca's more emotional moments, "We live in an era when people will not take emotions larger than life. They'll accept it in opera because everything in opera is so ridiculous. But they won't accept it when people are actually speaking words in coherent sentences."

It's the kind of thing that was probably great in Sarah Bernhardt's day, but with the advent of sound movies, you go to a movie, there's a certain realism in movies, a certain realism in plays. Dead End comes along and people say, yeah, that's how people really talk. Even in Philip Barry plays, it's highfalutin society talk and it's high comedy, but it's the way people talk. Only people like Maxwell Anderson did blank verse. Nobody writes like Oedipus Rex. Eugene O'Neill did. O'Neill went for the big gun. And sometimes that worked great, but not many people write that extremely stagy stuff anymore. Contemporary audiences, their patience level is so short. But when they see it—particularly in a grand house: one of the things about grand opera that people forget is that the size of an opera house suggests something to an audience and they accept the fact that everybody is committing suicide all the time and murdering each other and all that stuff in the big scenes. It's all part of the entire thing. Some operas, if they were done in a small house, would seem overblown. It's called grand opera for a reason.

Some people say Passion is an opera.

That's because so much of it is sung. And it's arioso singing. It's not the percentage. The percentage of dialogue to music is even less in Follies than in Passion. But the sung stuff is rarely songs. It's mostly arioso singing, extended song forms. That's what's vaguely operatic about it. It's free-form writing.

I think it works well.

I do, too. It was done last year at the Donmar Theater in London, which seats 270 people, I think, and it was the perfect location. It's a chamber opera. And it was done in a chamber.

Do you care about labels?

No, that's for people like you who have to describe something. You have to have a tag. Or, you don't have to but it makes it easier to write about something if you can call it something. I can probably tag everything if I had to, but I don't have to. It's only for people who have to describe what they've seen.

What do you like most about your work?

If you talk about my work meaning the songs, that's one thing. If you talk about the shows, they're our shows, because I think of shows as collaborative efforts. So far as my own songwriting goes, what I like most about it is that they're technically very good and they accomplish their purpose. Why I like the shows is more difficult to describe. I like almost all of them very much and for different reasons. They fulfill me on the grounds of something really funny, like A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, or the grounds of something moving—to me, anyway—like Passion, or something stark, like Assassins. They fulfill me on different levels, so as a member of the audience, I enjoy them very much. And there are failed experiments, like Anyone Can Whistle, but I don't regret it for a second.

You write in Look, I Made a Hat about how your teacher, composer Milton Babbitt, taught you about structure, about how whole works are made from tiny increments.

From Milton I learned about the structuring of themes, what he or someone called one-line composition, which is that there is a guiding principle to the whole arc of either a symphony or a song, which is itself reflected in many ways—just like the way King Lear's themes are reflected in its characters and subplots. So, we'd analyze, say, the Jupiter Symphony to see what Mozart was doing with structure, what Milton called the architectonic of the piece, the larger structure, and how it's reflected in the smaller structure so it all holds together and doesn't sound like something made of bits and pieces.

The whole idea is, how do you organize something that lasts over a period of time, so it seems like one piece instead of 20 pieces? And that period of time can be three minutes or it can be an hour; the principle remains the same. And that—using leitmotifs that develop out of smaller motifs—is something I've been doing for a long time, because in writing a score, you have music interrupted by dialogue, so what is it that holds the evening together? If you want to hold the score together—Cole Porter wasn't interested in holding a whole score together. He just wrote a lot of songs.

Do many people who compose musicals do what you've just described?

No, very few. It's just something that I like to do. A lot of people think they're holding the score together just by doing reprises of themes, but they're not developing anything. People talk about through-composed shows—there are not any through-composed shows. That's to begin with. All they are doing is just reprising motifs over and over again. That has nothing to do with composition. It has to do with reprising. They think that holds a score together, and it doesn't.

Compositional techniques don't interest most people. It must appeal to my puzzle mind. Also, I think it matters in the score.

It seems more subliminal. The discovery songs in Into the Woods, for instance, the songs of Little Red Riding Hood, Jack, and Cinderella, are all variants of the same melody, a melody that comes back, just for a couple of lines, in Act II, when the Baker's Wife has her epiphany. But the interesting thing is that they don't sound like the same song.

And they're not reprises. The two biggest examples of what I'm talking about are the scores for Sweeney Todd and Merrily We Roll Along, where the music is very much related to the characters and their relationships and there is an attempt to a make a score out of it rather than a series of songs. There's some of that in Into the Woods, but there it mostly has to do with the bean theme that ties those characters together [Ed.: Jack's magic beans are practically community property by the end of Act I]. Sweeney and Merrily are much more interwoven as scores. There's some of it in Pacific Overtures, but it really came to fruition with Sweeney.

A lot of times when I listen to cast recordings of your shows, I'm struck by how Broadway singers don't hear the structure that's in your stuff.

It's absolutely true. It's also because they're not used to it. They're not trained in opera. They're not trained to hear scores. They're trained to hear songs, and that's what they hear—self-encapsulated pieces. When Mandy Patinkin gave his last performance in Sunday in the Park, there was a little party for him in the basement of the theater, and I can't remember how it came up, but I mentioned that "Putting It Together," in the second act, was a variation on "The Day Off" sequence, which occurs in the middle of the first act. And his eyes widened. He'd been singing it for a year and a half, and it had never occurred to him that the two pieces were related. Most singers on Broadway are just not trained to hear that sort of thing. They hear songs, they don't hear scores.

I don't hear it unless I sit down and play the music.

And you're not meant to. It's supposed to be subliminal. But I'm convinced that having all that in there makes for a more satisfying experience, when there's that kind of interweaving, when there's that kind of resonance, just like there is in a libretto. In [the libretto for] Sunday, James Lapine has numerous resonances, in sentences and word, that occur throughout the entire evening, that lend a texture to the libretto that is not just a series of lines. It's a libretto, and it has musical aspects to it that have nothing to do with the music. And so, y'know, does A Streetcar Named Desire.

If you started out in the current climate of Broadway, would it be harder than when you started in the '50s?

I think so. Shows are just so expensive. There are fewer producers. Money is harder to raise. You don't get the kind of chance-taking you used to get. I can't imagine any producer today putting on Pacific Overtures or Assassins.

Even with your name on it?

Yeah, I don't sell those kinds of tickets. No author sells tickets. Only TV stars.

Did your opinion of your work change as you prepared these books?

I was surprise at how much I liked most of the lyrics. I am by nature self-deprecating and I was surprised. A lot of those lyrics are really good.

What's next?

I don't know. The books took four years to write. I had a good time doing it, and I'm glad I did it, but I've got to get back to writing music. I really miss it.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.