Fourteen years after invalidating state laws criminalizing gay sex, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on December 5 in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission .

The case concerns a Colorado baker—Jack Phillips—who refused to bake a cake for a male couple's wedding celebration, citing his religious objections to same-sex unions.

On its face, the case represents the clash of cherished American values—freedom of religion and expression on the one hand, and a freedom from discrimination on the other.

But Masterpiece Cakeshop represents more than just the collision of rights. It also reflects the limits of decriminalization as a vehicle for legal reform.

Yes, the Supreme Court's 2003 ruling legalizing same-sex intimacy paved the way for its recent decision guaranteeing the right to same-sex marriage. Indeed, decriminalization has been a prominent vehicle for legalizing and recognizing other core rights.

Over a generation, in a series of landmark cases, the Supreme Court invalidated criminal laws that prohibited birth control, abortion, and even interracial marriages, making all of this conduct legal.

But even when courts strike down criminal laws, the impulse to punish and stigmatize the conduct does not evaporate. Instead, it gets rechanneled into other, non-criminal forms of state regulation.

Although Loving v. Virginia legalized interracial marriages, in the years after the decision was announced in 1967, courts routinely terminated white women's custody of their children when they remarried outside of the race.

Likewise, though Roe v. Wade legalized abortion in 1973, many civil laws and administrative rules have emerged in Roe 's wake to communicate the stigma and disapprobation that still attends a woman's decision to terminate her pregnancy. As pro-choice advocates note, these civil rules and regulations may limit abortion access as forcefully as a criminal ban.

Jack Phillips's refusal to create cakes for same-sex weddings precedes the Court's decision legalizing same-sex marriage, but nevertheless, we might understand it as an expression of the continued disapprobation of same-sex intimacy and certainly the prospect of legalized same-sex marriages. Decriminalization and legalization does not mean complete acceptance or the absence of regulation. It simply redirects the regulatory impulse into new venues.

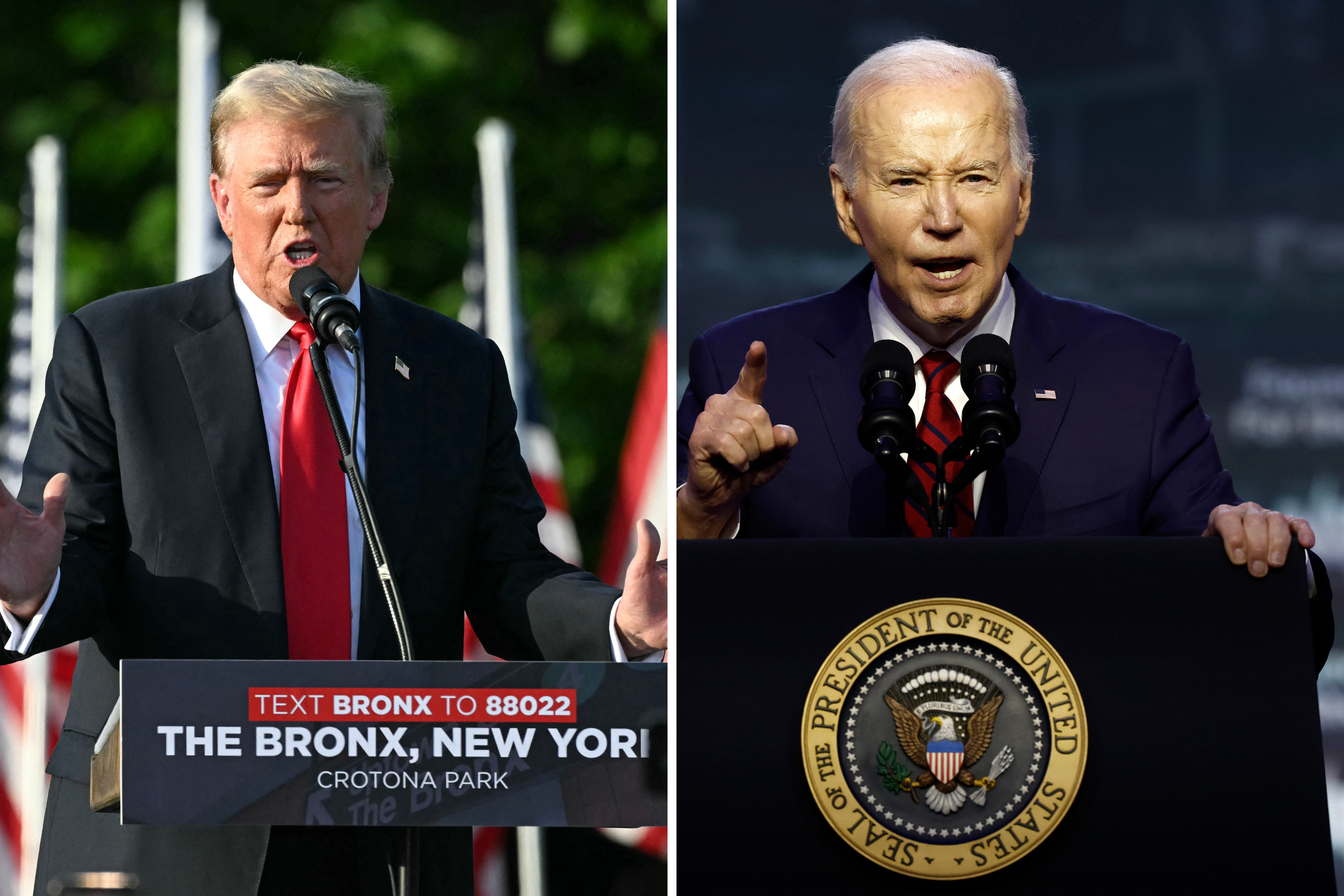

While regulatory displacement is nothing new—it routinely follows decriminalization of intimate conduct— Masterpiece Cakeshop , in tandem with the Trump Administration's recent decision to allow employers to opt out of contraceptive coverage because of their religious or moral objections, represents a new development in how conduct continues to be regulated, even after decriminalization.

When interracial marriage and abortion were decriminalized, the regulatory impulse was redirected into other areas the state regulated directly—custodial decision-making and civil laws that govern abortion services and providers.

In both Masterpiece Cakeshop and the new Trump Administration regulations, the disapprobation and regulation comes from a private individual—the baker or the employer—rather than from the state.

But make no mistake, even when the disapproval comes from a private individual, the state's regulatory presence lurks in the shadows.

In the case of the contraceptive exemption, the Trump Administration has essentially deputized private employers to express their objection to contraceptive use—and to ban coverage for employees. This move does not involve criminal penalties, but it has the potential to limit access to contraception as effectively as any ban.

Likewise, if the Supreme Court credits Jack Phillips's First Amendment claims and exempts him from the reach of Colorado's anti-discrimination law, it will effectively deputize Phillips—and others like him—to express their condemnation of same-sex unions by withholding goods and services.

While it is not the same as making same-sex relationships illegal, it nonetheless may give same-sex couples pause about revealing the nature of their relationship in public, pushing their relationships back into the closet that they occupied when such relationships were criminalized.

This is all to say that Masterpiece Cakeshop is not a case about cake—it is part of a larger conversation about decriminalization, legalization, and the persistence of state-sanctioned regulation of intimate life.

Melissa Murray, the Alexander F. and May T. Morrison Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley, is currently a visiting professor of law at NYU.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.