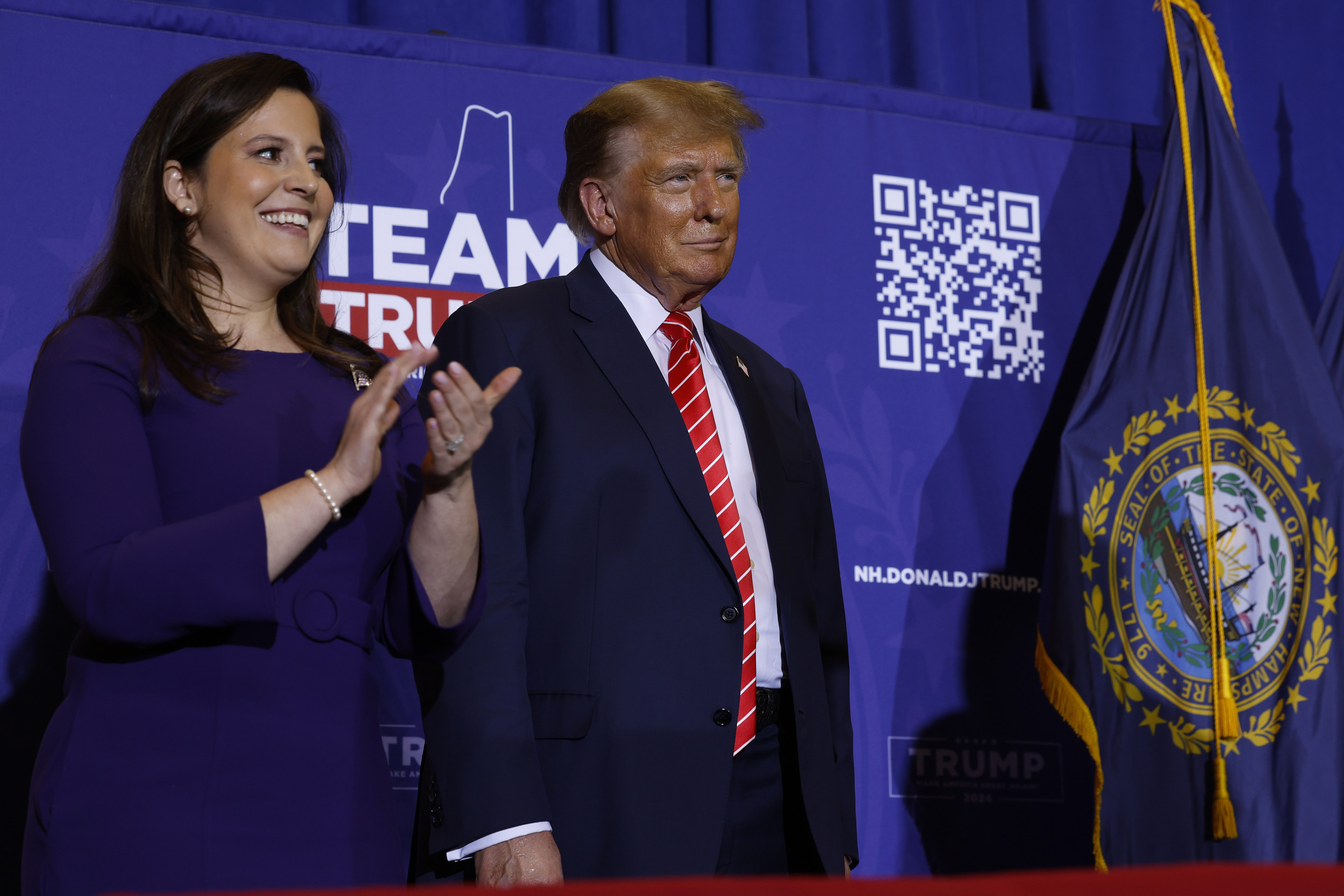

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

The Bradley Effect is dead! Long live the Obama Effect!

Or at least that's the cri de coeur coming from conservative circles as the 2008 presidential race enters its final sprint. Writing this morning for Salon and the Weekly Standard, a pair of political consultants--Bill Greener (a Republican) and Arnon A. Mishkin--seize on the same statistical argument to explain how John McCain, who trails Barack Obama by 7.3 percent in the latest RealClear Politics national polling average, could still win the White House eight days from now. Neither operative claims that pre-election polls are overstating the black candidate's support--perhaps because research has shown pretty convincingly that the Bradley Effect no longer exists (if it ever did). Instead, both posit the existence of an Obama Effect. According to this theory, most undecideds are actually decided--for McCain. Which means, in turn, that the Republican nominee will benefit from a big boost on Nov. 4.

Greener and Mishkin advance different explanations for their hypothesis. Mishkin attributes it to "social acceptability." Given Obama's overwhelming momentum, he writes, "it seems likely that if voters are not ready to tell a pollster that they are with Obama, they are unlikely to get there... Where there is a perception that there is a 'socially acceptable' choice, respondents who do not articulate it are likely not to agree with it." Greener, meanwhile, is more blunt. "If you're a black candidate running against a white candidate, what you see is what you get," he writes. "And it doesn't matter whether you're an incumbent or a challenger. If you're not polling above 50 percent, you should be worried."

So should Obama be worried?

I'd say no. As always, the standard caveat applies: anything can happen between now and Nov. 4. But there are a few problems with the Greener/Mishkin theory--at least as an explanation of why McCain might still win (a claim, it should be noted, that only Greener makes).

First of all, Greener's argument that undecideds break overwhelmingly against black candidates on Election Day doesn't really hold water. As evidence, he points to four races from 2006--the Tennessee and Maryland senate races and the Massachusetts and Ohio governor's races--then compares the pre-election polls to the final results. In each case, he says, the black candidate's support held steady while the white candidate's support shot up. Unfortunately, Greener chooses to cherry-pick surveys that support his thesis instead of using the more comprehensive RCP averages as the basis of his comparison. As a result, his conclusion is misleading.

Tennessee--where black Democrat Harold Ford was up against white Republican Bob Corker for Republican Bill Frist's old U.S. Senate seat--is a good example. "The day before the election, [Ford] was within a point of Corker, 47 to 48 with 5 percent undecided, according to OnPoint Polling," writes Greener. "On Nov. 7, Corker got 50.7 percent of the vote, Ford got 48 and an assortment of independents took 1.3 percent." But OnPoint was the only pollster to show a one-point margin; the RCP average, in fact, put Corker ahead by six, 50.3 percent to 44.3 percent. On Election Day, Ford earned 48 percent of the vote to Corker's 50.7 percent--meaning that it was Ford whose support shot up the most (by 3.7 points, compared to 0.4 points for Corker). In other words, more undecideds broke for the black guy than white guy. Likewise, Ed Rendell (a white Democrat) beat Lynn Swann (a black Republican) by a slightly smaller margin in Pennsylvania (10.8 percent) than the polls predicted (11.8 percent). But Greener simply ignores the Rendell-Swann race.

The rest of Greener's examples aren't quite as misleading. In Massachusetts, Deval Patrick (a black Democrat) gained less than two points on Election Day; his white challenger (Kerry Healy) gained nearly six. In Maryland, Michael Steele (a black Republican) lost nearly a point at the ballot box; opponent Ben Cardin (a white Democrat) gained more than five. And a similar (if slightly smaller) pattern cropped up in the Ohio gubernatorial race between Ted Strickland (white Democrat) and Ken Blackwell (black Republican). That said, these differences aren't statistically significant (as Nate Silver, who beat me to the punch by a few hours, has pointed out). On average, black candidates gained 1.6 percentage points on Election Day; white candidates gained 3.6 percent. With mixed results (see: Tennessee and Pennsylvania) and a dearth of data points, it's pretty hard to conclude that an Obama Effect will inevitably "rear its head" in the general election--let alone influence the outcome. What's more, two of the three white candidates who overperformed on Election Day 2006 were Democrats as well--and in 2006, a disastrous year for the GOP, "Democratic candidates overperformed their polls in a significant majority of competitive races around the country," as Silver notes. That leaves Greener with only one applicable case study--Patrick versus Healy. Not exactly a solid foundation for a grand theory of voter behavior.

Which brings up to the second problem with the Obama Effect. Not only does history disprove the notion that with black candidates (or "socially acceptable" candidates), "what you see is [always] what you get"--it proves that, for Obama, the reverse is true. As Silver showed back in August, the Illinois senator actually outperformed the polls by an average of 3.3 percentage points over the course of the entire primary season. In the West, he did 1.1 percent better than pollsters predicted (on average). In the Midwest, he surpassed the surveys by 3.1 percent. And in the South, he exceeded expectations by a whopping 7.2 percent. The only region where Obama underperformed, in fact, was the Northeast (where he can most afford to lose a little support); there, he finished about two points below the pre-primary trendline. As I recently reported, this leap is probably the result of pollsters underestimating the turnout of Obama's young and black supporters, who are voting in higher numbers this year than ever before. Ultimately, McCain may very well clobber Obama among late breakers, as Hillary Clinton did during the primaries. But if past is prelude, the boost that Obama receives from "expanding the electorate" will be at least as large as his opponent's gains among undecideds.

The final issue with the Greener/Mishkin theory is the most devastating. Both consultants argue that "as the election winds down, one should look less at the difference between Obama and McCain, and more at the actual number that Obama is getting in the polls"--largely because of McCain's assumed advantage among undecideds. And that, according to Greener, is why Obama should be worried: "[he] needs to be polling consistently above 50 percent to win. And in crucial battleground states, he isn't." The only problem? Obama may not be polling consistently above 50 percent in some "crucial battleground states"--but he's polling consistently above 50 percent in enough of them to win. Presumably, Greener is cherry-picking his polls again. According to the RCP swing-state averages, Obama leads by more than eight points and pulls down more than 50 percent support in every John Kerry state as well as the Bush states of Iowa and New Mexico, bringing his electoral vote count to 263. In addition, Obama's beating McCain 51.7 to 44.5 in Virginia and 51.3 to 44.8 in Colorado. That puts the Democrat at 286 electoral votes--and again, that's if we're only counting states he's polling above 50 percent. In other words, McCain could sway every single undecided voter--i.e., Greener and Mishkin could be completely, 100-percent correct--and Obama would still win the election by 224 electoral votes, at least according to the latest polls.

The bottom line is that even if the Obama Effect did exist--which is probably doesn't--it wouldn't be enough to propel McCain to the White House. To do that, the Republican needs to start convincing Obama's supporters to jump ship. And he's running out of time.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.