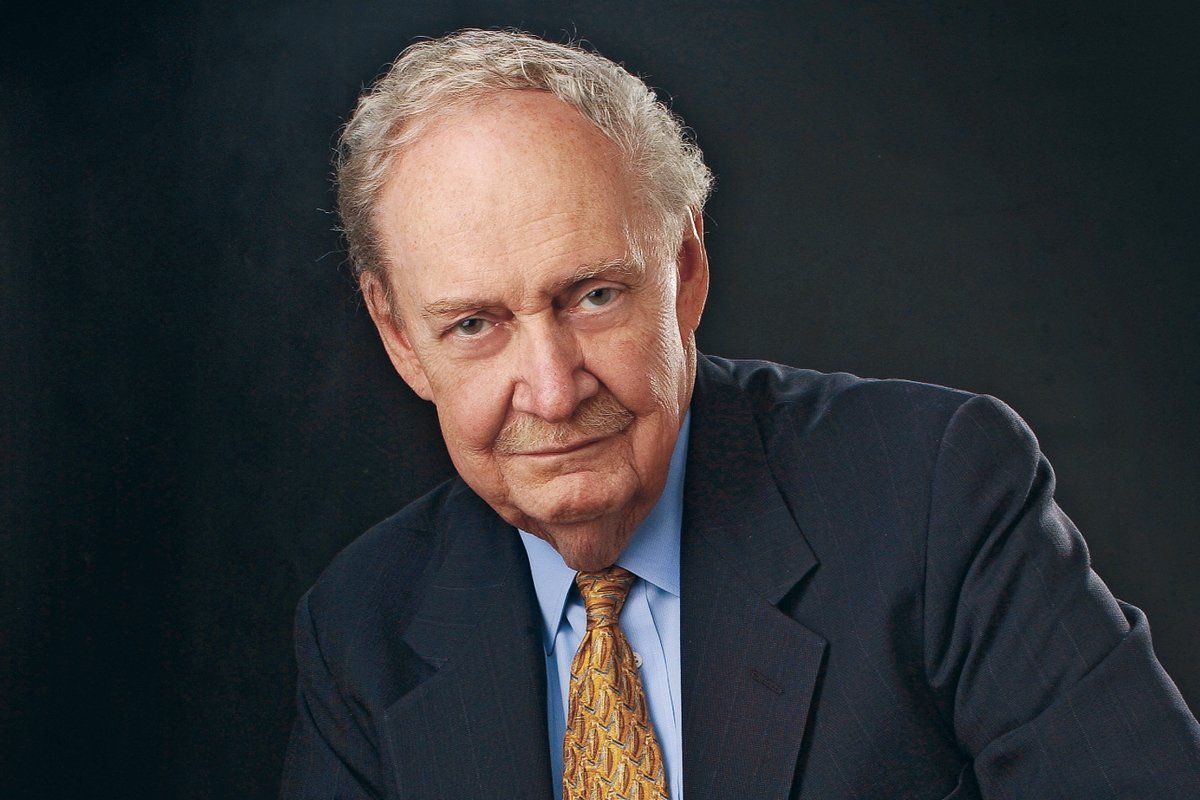

It's a safe bet that Robert Bork's obituary—whenever that cheerless day arrives—will bang on for many paragraphs about his historic role in Richard Nixon's "Saturday Night Massacre" at the height of the Watergate scandal, and his ordeal as Ronald Reagan's spectacularly doomed Supreme Court nominee, before it mentions that he was Mitt Romney's presidential campaign legal adviser.

"I'd like to know how you know what my obituary is going to say," Bork gruffly demands when I suggest the above-mentioned scenario. In any case, he adds, "I have no control over it—so I refuse to worry about it."

Still, the obit will duly note that during the 2012 election cycle, Bork signed on as co-chairman of Romney's "Justice Advisory Committee."

The Judge, as many people call him these days (owing to his six-year stint in the 1980s on the prestigious D.C. Court of Appeals), is 84 now, and spends most of his waking hours sitting in an armchair at his suburban Virginia home. He no longer wears the trademark beard, which gave him the look of a Viennese pedant (and inspired the appearance of Judge Roy Snyder on the animated sitcom The Simpsons). "When I first grew it, it was full and red," Bork says, "and gradually over time it became sparse and white. So I figured the time had come to get rid of it."

With the help of his wife, Mary Ellen, the former nun he married 29 years ago after his first wife, Claire, died of cancer, he's fighting the depredations of old age while keeping intellectually sharp as a distinguished fellow of the Hudson Institute, a conservative Washington think tank.

"I am doing some work, but I am also confined to the chair for the time being," Bork says over the phone as Mary Ellen listens in. "Oh, my wife wants me to tell you about I book I'm writing. The working title is '1973.'"

That was the year Bork, who'd left a professorship at Yale Law School to become solicitor general of the United States, was pressed by President Nixon to fire Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox after both Attorney General Eliot Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus refused Nixon's order and resigned instead. Cox's investigation was getting too close for comfort, and Nixon was in full cover-up mode. "It was," Bork says with droll understatement, "a busy time."

Bork says he has known Romney, the on-and-off-again Republican frontrunner, for the past decade and supported his candidacy last time around as well as during the current race.

"I get an impression, a very strong impression, of competence," Bork says, adding that "in addition to his undoubted skills as a businessman and a governor, Mr. Romney stands out as a leader." Bork confides about his role in the campaign: "I'd like to be asked a question now and then for advice. But that's about the extent of it." As for his initial attraction to the former governor of Massachusetts, "The first thing that grabbed me about him is, he's not Obama."

Bork's objection to President Obama?

"Aside from wrecking the economy and giving away a lot on foreign policy, I haven't got any objections," he retorts.

Any thoughts on Attorney General Eric Holder, who's embroiled in a controversy involving gun-running, the Mexican drug cartels, and the murder of an American border patrol agent?

"If we're talking about 'Fast and Furious,' my thoughts about that is, it's utter incompetence—primarily of Holder but I wouldn't put it past the president to have gotten involved," Bork says. "At the very least, the consequences should involve Holder's dismissal from office. There's always a question about whether you exercise criminal jurisdiction over an executive-branch officer. But that means there's all the more reason to dismiss him."

What's Bork's take on Obama's two Supreme Court appointments, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan?

"They are going to be activist justices," he asserts, not without distaste. "I'd be more concerned if the other sitting justices were older. But they—the justices with whom I agree—are young enough to last into the administration that follows Obama. So it's going to be more of the same. But that's fine, because more of the same isn't worse."

Bork, who tends to pursue his legal theories without regard for their political consequences—a sometimes admirable quality that did him no favors during his own nomination hearings in 1987—has argued that the Constitution should be amended so that bad Supreme Court decisions can be reversed by Congressional supermajorities.

I ask him why he'd propose such a radical notion.

"Because the Supreme Court, since the 1930s, has been a runaway court," he insists. "And I think there ought to be a form of democratic control over the court's wilder adventures."

Does he think Romney should adopt that position?

"Aside from wrecking the economy and giving away a lot on foreign policy, I haven't got any objections" to Obama, Bork says.

"It would gather a lot of opposition," Bork acknowledges, "so I don't know that I would thrust Mitt Romney into the midst of that."

Another Bork position Romney probably won't have to defend was his opposition to the landmark civil -rights legislation of the 1960s. Bork criticized the legislation on the ground that government coercion of "righteous" behavior is "a principle of unsurpassed ugliness." And now?

"That was a reflection of what I thought at the time, because I said it," he acknowledges. "But, heck, it was a long time ago. And it turns out that the transition to a non-discriminatory society was much easier than I thought it would be. I am now perfectly happy with the way things turned out."

Not that Bork is as flexible as his candidate—who has migrated from liberal Massachusetts Republican to, if one takes him at his word, committed conservative. For instance, I ask Bork if he still disagrees with the high court's Griswold v. Connecticut ruling that married couples have a constitutional right to the use of contraception?

"Oh, my God, yes!"

And does he still believe that the First Amendment should be limited to political speech and not protect, as he once wrote, "any other form of expression, be it scientific, literary or…pornographic"?

"Oh yes!" he answers enthusiastically. "If you look at what they say, the First Amendment supposedly defines things like child pornography. The Supreme Court said there was a right to it. That's actually insane."

How about the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment? Does he still think it shouldn't apply to women?

"Yeah," he answers. "I think I feel justified by the fact ever since then, the Equal Protection Clause kept expanding in ways that cannot be justified historically, grammatically, or any other way. Women are a majority of the population now—a majority in university classrooms and a majority in all kinds of contexts. It seems to me silly to say, 'Gee, they're discriminated against and we need to do something about it.' They aren't discriminated against anymore."

Bork, who famously (and fatally) told the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1987 that he wished to be an associate justice because the work would be "an intellectual feast," understandably has a hard time letting go of ill feelings toward the senators who caricatured and vilified him.

Even before the confirmation hearings, Ted Kennedy went on the Senate floor to describe "Robert Bork's America" as "a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens' doors in midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists would be censored at the whim of government," and so on and so forth.

I ask Bork if he ever forgave the late Kennedy.

"I'm trying to think of how I could conceivably do that," says Bork, a convert to Catholicism. "We're supposed to forgive all kinds of behavior. I shouldn't deny that I've forgiven somebody, or I'll end up being assigned to the outer circles of Hell. But Ted Kennedy is a test case of the limits of forgiveness.

How about Joe Biden, who chaired his Senate hearing?

"Oh, poor Biden," Bork says with mock sympathy. "Biden, I think, is not a very thoughtful or intelligent man."

Indeed, the attacks on The Judge were so well coordinated and relentless that the verb "to bork"—meaning "to attack (a candidate or public figure) systematically, especially in the media"—can be found in some dictionaries.

"Well," the Judge says ruefully, "that's one form of immortality."

This is an extended version of an interview that appeared in this week's issue of Newsweek.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.