While researching their forthcoming book about American religion, the Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam and his colleagues polled on this hypothetical question: Say a group of Buddhists wanted to build a large temple in your community. How would you feel? Putnam & Co. asked about Buddhists because, they had discovered, Buddhists are one of the least popular religious groups in the country. People like Buddhists less than they do atheists and Mormons—and only slightly more than they do Muslims. Like Muslims, Buddhists "do not have a place in what has come to be called America's Judeo-Christian framework," Putnam and his coauthor, David Campbell, write in American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us. The book comes out next week.

What they found was, in light of the recent controversy over the proposed community center and mosque near Ground Zero, disturbing but not surprising. Three quarters of Americans said they would support a large Buddhist temple in their community, but only 15 percent would explicitly welcome one. Americans, in other words, supported the idea of a temple but weren't so crazy about the bricks-and-mortar aspect of things.

Three years ago, when they asked the question, the authors of American Grace could not have known how prescient they would seem. Polling last week from Quinnipiac University revealed exactly the same paradox. Seventy percent of Americans support the rights of Muslims to build the mosque, but 63 percent believe it would be inappropriate to actually build it. The polls give Muslims the same rights in principle as everyone else, but they show a basic mistrust of Islam and so corroborate Putnam's conclusion that Muslims, like Buddhists, are not yet part of "America's Judeo-Christian framework." "It really is a question of whether Islam can be seen as a fundamentally moderate faith, within the range of faiths that are part of American civil religion," explains Wilfred McClay, a historian at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. "Or is it a permanent outlier?"

The story of American religion has always been marked by this fragile tension. On the one hand, we value tolerance and pluralism above all, and we will fight for our neighbors' right to practice as they please. "It does me no injury," Thomas Jefferson wrote, "for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg."

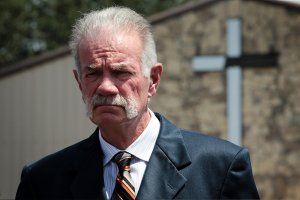

But the American religious landscape has also forever been peopled by zealots and prophets—people who believe, rightly or wrongly, that theirs is God's way, all others be damned. The peace we hold and say we value has been broken, time after time, by religious leaders who reject—often violently—the beliefs of a new, immigrant, or breakaway group. Thus the Puritans regarded Quakers as infidels and treated them accordingly: whipping and imprisoning some, executing others. In 1834, fearing the encroachment of an "evil" religion, a mob of Protestants burned an Ursuline Catholic convent near Boston. Four years later the governor of Missouri announced that all Mormons had to leave his state or risk execution. The Islamic center is one more chapter in this story. "When pressed, people's desires to defend their neighborhood, or the lives of their children, qualifies and sometimes overwhelms the pluralist impulse," explains Grant Wacker, who teaches American religious history at Duke. The anti-Muslim slurs, the protests, the simmering violence, and the buffoonery of a certain Florida pastor who threatened to burn Qurans are shameful and not without historical precedent. (The global media attention given to them thanks to the Internet is.)

With time, Jeffersonian ideals in America have historically eroded the sharp edges of sectarianism. Eventually, gradually, most of us reach across divides to embrace the alien other. According to American Grace, a third of us marry outside our faith traditions; if you count conversions, that number jumps to a half. More than 80 percent of Americans say they believe that people of other religions can go to heaven. Despite the persecutions of the past, we have had a Quaker president, a Catholic president, and Mormon presidential candidates. In recent weeks, conservative Christian leaders have begun in blog posts and newspaper advertisements to rebuke their intemperate brethren, a slim but hopeful sign of Americans' grace.

Lisa Miller is NEWSWEEK's religion editor and the author of Heaven: Our Enduring Fascination With the Afterlife. Become a fan of Lisa on Facebook.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.