On June 2, 20-year-old Sabina Rose O'Donnell was sexually assaulted and strangled to death behind her apartment building in Philadelphia. As the police investigated, and as the local press digested the story, one of the city's most recognizable figures—someone who just so happens to be on network TV every night of the working week—counted himself among those captivated (and depressed) by the story of her murder. Ahmir "?uestlove" Thompson is, today, many things. He is a familiar and much-watched presence on the Internet (with 1.3 million followers on Twitter), as well as a focal point of stylebook disputes between music journalists and their copy desks (his nom de plume is pronounced "Questlove," though he spells it with a "?"). Most importantly, he is the drummer for the long-running band the Roots, who, after 15 years of making politically engaged hip-hop with (mostly) live instruments, took the unlikely but brilliant gig in 2009 as the house band for Late Night With Jimmy Fallon on NBC. And yes, it turns out that ?uestlove was also an acquaintance of O'Donnell's.

"Two weeks went by, and it was easy to get caught up in," he says one afternoon while en route to the 30 Rock building in midtown Manhattan, where Late Night is taped. "Everyone's talking about the monster who did this, you know? You have those 'check that motherf--ker' lynch-mob scenarios in your head. Then they caught the guy yesterday, and I almost wanted to break down and cry—literally, like a baby. Because he [the suspect] just turned 18 years old, and there was something in his eyes. It was like: 'Yo, I was not expecting this to be the animal.' So I kinda went long on Twitter yesterday about how I think that, more important than getting justice for our friend's murder, we actually sort of need to investigate what would make someone 18 turn this nihilistic."

Not everyone was happy to hear it. "That empathetic view of it didn't go down too well with the city of Philly," he says—not with the reflexive contrarian's enthusiasm, but instead a sincere sadness. When he adds this grace note, ?uestlove isn't suffering from the average celebrity's "this town revolves around me" brand of self-delusion, either. (The Philadelphia City Paper had already posted ?uestlove's controversial Twitter essay, in which he imagines how, but for the grace of God, he could have traveled down the same road as O'Donnell's killer.) The fact that anyone cares what this particular drummer thinks about a local tragedy is because he has put in the effort to become a sort of good-will ambassador for the city.

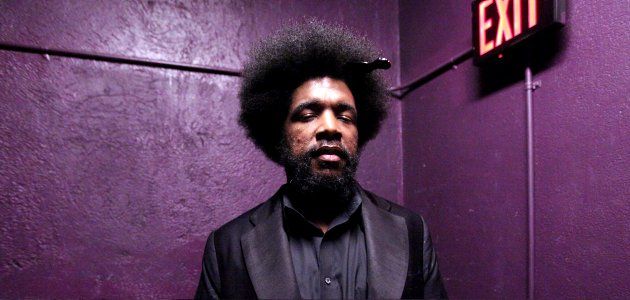

The first time I meet ?uestlove in person is at a function for Philadelphia's summer arts festival held at the see-and-be-seen grazing spot for New York media's power lunchers, Michael's. Seated, guest-of-honor style, at the middle of the long table of reporters, ?uestlove has a natural way of commanding the room's attention—given his combination of an approachable demeanor with a 6-foot-2 frame and one seriously impressive afro. Halfway through the lunch, though, his phone rings. It's time to get to the studio for the evening's Fallon taping. As ?uestlove rises and makes his apologies to the table, he holds his phone aloft and invokes the fictional NBC executive played by Alec Baldwin on the sitcom 30 Rock: "It's Jack Donaghy telling me to get my ass over there." Everyone laughs. The publicist for Philadelphia's summer arts series appears sad to see him go—and sure enough, the lunch becomes a lot less fun after he does.

Between these two anecdotes rests the central paradox of ?uestlove's popularity: few celebrities today are as cross-platform enjoyable as he, and yet even fewer still are equally possessed of a contemplative—even sad—streak. The drummer who can set a world record for holding afro picks in his hair (101, to be exact) is the same guy who wonders whether justice is better served by vengeance as opposed to a deep structural rethink. Since ?uestlove has established reputations for frivolity as well seriousness, sometimes his audience can't be sure about the mode in which he intends to communicate. "I tend to wonder if I'm running away from the human experience and using entertainment as a means not to deal with regular life," he told me. "Don't get me wrong; entertainment is the most golden life ever. But if you come to my house, it's the same jar of mayo sitting in the refrigerator from 10 years ago. I mean, I'm kidding—but it's not that exaggerated. I don't have kids; I don't have a life. I consider my career and its many offspring to be my life, for the moment."

Sometimes his dual nature can lead to confusion. In February, ?uestlove posted a photo of the NBC cafeteria's lunch options to Twitter. In "honor of black history month," the menu read, the cafeteria would be serving traditional soul-food items, such as collard greens and fried chicken. "Hmm HR?" ?uestlove asked. Soon, the Internet came alive with "oh, no, they didn't" objections to the cafeteria's culinary stereotyping. NBC took down the menu, and ?uestlove later wrote that he'd posted his photo because he found it funny, not because he thought it was offensive. (Ultimately, he treated the cook who drew up the menu to a lavish spa gift certificate.)

?uestlove claims that the confusion, as much as it may crop up, is borne of the reality that hip-hop musicians are not often seen as three-dimensional individuals by the culture. "Rarely is there a vulnerable side to anyone in hip-hop. There's always a strong-front thing. Even in the face of the adversarial, like with TI facing jail time." As a result, he says, Fallon's writers took their time before inviting the group to perform in sketches. "They learned about us from our records, and so they thought, 'You guys wouldn't be interested in sketches, would you?' And we said, 'What took you so long? That's exactly what we want.' " Now that he and his band have settled into a groove on Fallon's show—showing their flexibility by backing up a wide array of musicians and providing smirking musical cues for guests—?uestlove could keep himself occupied with humorous appearances and media parties all the time, if he wanted to. He could confine his online musings to the topics on which he is indisputably an expert, and thereby prevent the grim details of life outside the "charmed, I'm sure" media bubble from having the opportunity to unsettle him. If he wanted to demonstrate his commitment to "public issues" such as O'Donnell's murder, he could limit his involvement to fundraising for the victim's family (which he has also done). That he doesn't stop there—that he's willing to risk vulnerability and anger in real time—actually helps explain the music ?uestlove and the Roots make.

It's not hard to see how Fallon's writers might have thought the Roots would turn out to be uncertain comic material. In addition to their exquisitely well-chosen rhythms, the band's albums can feel like serious, labored affairs—as if the artists responsible were guilty of reaching for too much at once. The upside to this method is delivered by shots of "whodathunkit" inspiration: how the hour-plus Phrenology, from 2002, dips into hard-core punk, or how Rising Down, from 2008, flirts with Fela Kuti–style Afrobeat. Somewhat curiously for a band that traffics so reliably in jam, there is seldom a carefree party anthem to be found, however. So when it comes out tomorrow, How I Got Over—the band's ninth studio record—will likely prompt a familiar range of critical nattering: praise for ?uestlove's drumming and production (both of which are sought after by other artists), some debate over whether lead lyricist Black Thought has sufficient "charisma" as a rapper, and the question over whether it amounts to music that's as great and lasting as the band clearly intends for it to be. When you name your albums after Chinua Achebe novels (Things Fall Apart) or gospel songs made classic by Mahalia Jackson (How I Got Over), you're making no bones about ambition—an attitude ?uestlove echoes when he claims that there are few examples of hip-hop artists staying vital into their 30s and 40s.

"Jay-Z was really the first MC to comfortably embrace maturity and age," ?uestlove says. "But because he is such a cult of personality, his vision of approaching or turning 40, um, is more—dare I say?—romantic than our version. So this is probably our most personal record to date in terms of asking what happens to us and why. I mean, no one else would put a song about questioning God in the No. 3 spot on the album." Certainly, the gospel references on How I Got Over are unmistakable, from its reworking of the Monsters of Folk song "Dear God" right down to the acoustic piano that dominates a number of songs. ?uestlove says this happened organically, since the studio that the Roots asked NBC to build in their dressing room at first only had room for a Hammond B3 organ and a piano. But neither does he deny that the sound of the piano often dictates the mood of a Roots record. Whereas the first Roots albums had a mellow, jazzy keyboard feel and their work during the George W. Bush years sounded more electrically wired (and angry) than usual, How I Got Over hits a calmer, more somber note—though one that ultimately seeks to uplift. ("The Fire," which features John Legend, made its debut at the Winter Olympics opening ceremony in Vancouver earlier this year.) In the song "Web 20/20," rapper Black Thought references John Mayer's jaw-dropping comments on race from last year when he says "f--k a 'hood pass'/my s--t's all-access," which is another way of saying everyone is invited to partake of these thoughtful and world-weary joints if they like.

That inclusiveness is nothing new for the Roots, either. "There's always two guaranteed things at a Roots show," ?uestlove says, with nearly two decades of experience in the matter. "There's the confused black demographic, that's always scratchin' their head, looking around and thinking, 'We didn't' know that you were this loved,' because the whole audience looks like a Benetton ad. And then there's the one white fan that wants to apologize for all the other white fans, saying, 'I been down with y'all from day one. I'm not like these other white people.' " The band's multidemographic appeal may only be jacked up to higher levels by How I Got Over because its guest list is studded with major names in indie rock, such as Joanna Newsom and singers from the Dirty Projectors. Amusingly, though, ?uestlove isn't just willing to tell tales on other people's assumptions about musicians and who ought to enjoy them. He can also tell that same story on himself. When the Dirty Projectors dropped by the Fallon show late last year, ?uestlove dashed off a snarky Twitter post. ("imma take a wild guess dirty projectors are from BK [Brooklyn]?," he quipped—a little dig at how hipster rock bands from the borough tend to look and dress—and sometimes sound—alike.) But then ?uestlove was blown away by the precision of the band's complex, richocheting vocals on the broadcast. "That was the sucker punch of life. They blew me away. Every time I've seen them in concert since, it felt breezy and comforting a little bit. I knew that somehow I wanted utilize their Ping-Pong style of singing as a welcoming sort of opener." ?uestlove sees that wish fulfilled on "A Peace of Light," the first track on How I Got Over. In it, the three female singers from the Dirty Projectors sing a slightly off-kilter melody, distantly reminiscent of doo-wop, though not quite anything most listeners are familiar with. Think Sun Ra's early experiments with female vocal groups.

After Michael Jackson's death last year, I e-mailed ?uestlove and asked him to contribute his thoughts to NEWSWEEK's "end of the decade" editorial package. He called me back and asked if he could just riff on some ideas, which I would condense and send to him via e-mail for a revision. At that point, How I Got Over had been pushed back for more recording several times, and ?uestlove told me he was spending the extra months on the album out of respect for Jackson's own meticulous creative process. But then, without prompting, he also hinted at some larger questions about what he called "the psychological state of most black geniuses" in the music industry. "A lot of the routes are jail, drugs, religion, or death," he says. In considering Jackson's tragic fate, ?uestlove's imagination was prompting him to wonder whether the workaholic black genius script was a healthy one for him to be living out—in much the same way that, this month, he's been asking his hometown hard questions about how Sabina Rose O'Donnell's killer comes to be created.

Naturally, most of ?uestlove's morose-sounding self-reflection was edited out of his remembrance of Jackson. The entry became less about ?uestlove's worries and more about the artist who brought a measure of joy to the public. But in light of his recent writing about O'Donnell, I went back to read the entirety of our old conversation again. The same talent for empathy is evident, as is the desire to understand—and give hope: to figure out how all of us can get over, too. The press materials for the Roots's new album claim that it represents the "post-hope" zeitgeist in America, but I think that's slightly off the mark. Hope seems to be something the band, and ?uestlove, aren't at all finished with—in their music, in their television appearances, or on Twitter. And the very thing that can seem strange about ?uestlove in our current celebrity culture—his ability to pivot so quickly from thoughts of exultation to those of sadness—makes sense in the context of an album titled in honor of a gospel-music giant. In the spots on How I Got Over where he and the band (and their collaborators) work that distillation to near perfection, all I find myself wanting to say is "preach."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.