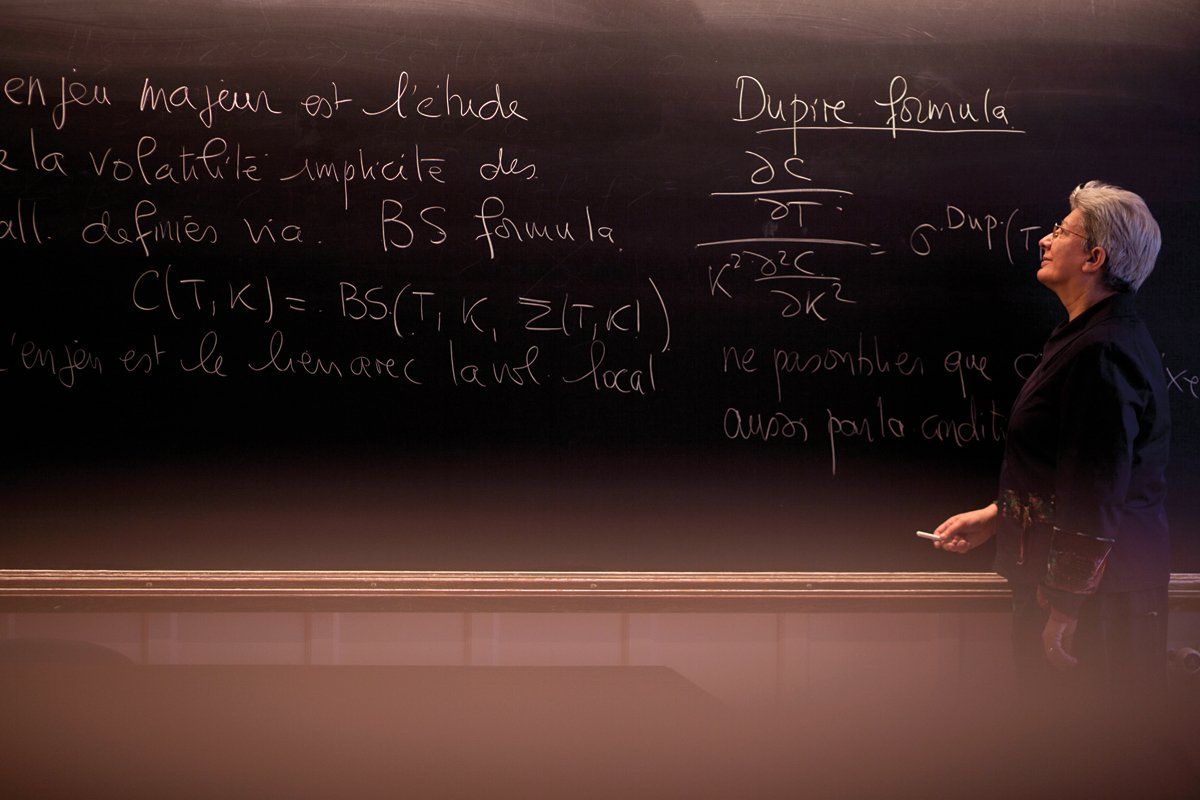

At the height of her fame in the middle of the previous decade, Nicole El Karoui had the imposing look and the unassailable authority of a French schoolmistress. She would lecture for hours, often speaking softly to the equations she wrote on the blackboard, while her students at the University of Pierre and Marie Curie (also known as Paris VI) listened with rapt attention—or, in quite a few cases, incomprehension. A quarter of them would flunk out. But those who survived her course on the mathematics of finance went on to be treated as geniuses in the world of big money. Then, around 2006, Professor El Karoui started wagging her finger at some of her alumni. If she'd had a ruler to rap their knuckles, that might have been a good idea, too.

El Karoui, now in her late 60s, adored her subject, and she always found math more intriguing than money. Nevertheless, she played a central role in the proliferation of the financial theorists who became known as quantitative analysts—quants, as the investment world calls them. Many of those imaginative number crunchers, in turn, played a major role in the wild explosion of esoteric financial instruments before the crash of 2008. The respected daily Le Monde estimated at the time that one in three quants in the world hailed from France. And ever since the global financial meltdown, every time a few billion dollars evaporate, someone French seems to wind up in the headlines. The most recent: Bruno Iksil at JPMorgan Chase & Co., who was the first person named, though not the last, in the bank's stunning loss of $2 billion and counting.

Amid the storm of crazy accusations that quants were somehow responsible for crimes against humanity, El Karoui has stopped giving interviews. A mutual friend sent me a note last week: "She no longer talks to the press." But like the teacher who has eyes in the back of her head when she's up at the blackboard, she saw clearly where her ambitious students, high on risk and volatility, were likely to go wrong.

The equations she had developed and taught could work well (though not infallibly) as a hedge against market risk. Instead, however, they were being used to create exotic financial products that were sold to investors and speculators at enormous prices. "Some clients aren't mature enough to understand the risks of products that are too complex," the stochastic-calculus schoolmarm told The Wall Street Journal in 2006. "It's better to do business with those people responsibly, either taking the time to teach them or selling them a less complex product."

The problem, of course, is that very few people actually speak the creative, coded language of mathematics that's required in order to understand derivatives and elaborate hedges like those that Iksil worked on. Indeed, while he's expected to leave JPMorgan Chase in the near future to show that management is still acting managerial, there's some concern that no one else in the shop could grasp all the moving pieces in the enormous hedges he'd constructed. Such men and women dream in equations—and in French.

In fact, the tutelage of El Karoui and her colleagues is only one of the reasons that France has produced so many of the mathematicians who have been behind the financial world's stupendous gains—and losses—in recent years. For starters, basic education in France puts a strong emphasis on pure mathematics. But more than that, at the higher levels there's a persistent fascination with the theoretical workings of the marketplace, dating back at least to 1900 and the pioneering work of Louis Bachelier. By the 1990s, many French universities were developing programs devoted to "the very, very complex modeling of derivatives," in the words of one young French veteran of the City of London's supercharged trading scene.

London is a magnet for France's young financial professionals. They often prefer to work in what they call "Anglo-Saxon" environments (New York is another). Job openings are more abundant, salaries and bonuses aren't so heavily taxed, and the culture admires success rather than envies it, as often happens in France. And there's one advantage New York can't match: in London, French transplants are blessed with easy weekend commuting via the Eurostar, which now runs from the heart of Paris to the heart of London in two and a half hours. The young City of London veteran, an El Karoui disciple who prefers not to have his name in print, recalls his years at a major British bank where his team eventually numbered roughly 40 members, at least 75 percent of whom were either French or had a French educational background. Among the elite schools they attended: Paris VI with El Karoui, the ESSEC international business school, and the Université de Paris Dauphine—three of the many French temples of financial learning where formal mathematics is emphasized.

Because those diplomas wield so much promise and pressure in the financial world, young traders with lesser credentials sometimes make reckless bets in hope of proving their worth. That appears to have been the case with Jérôme Kerviel, whose purportedly "rogue" trades brought Société Générale to its knees in early 2008. He was a graduate in finance from the University of Lyon—the provinces, one might say. On the other hand, "Fabulous" Fabrice Tourre, allegedly the bane of Goldman Sachs in 2010, was a product of the much more elite École Centrale Paris, a top-flight engineering school, and yet his employer found it necessary to pay out more than half a million dollars in fines related to his work. Iksil reportedly also attended the École Centrale. Colleagues referred to him as "The Whale" because he took such huge positions in the markets where he operated. Others less sympathetically called him "Voldemort," after Harry Potter's nemesis.

Just what did these sorcerer's apprentices do all day? The City veteran tries to explain to a non-math-speaker. Let's say you want to develop a financial product that will protect investors with huge amounts of money against various contingencies in the market. "The people who build the models are the technical guys, and those are called the quants," says the veteran—"quant" being short for quantitative analyst, as you'll recall, although the math can be reminiscent of quantum physics in its incomprehensibility. "Everything is very mathematical in derivatives, and it is pure math, even though we say it is applied mathematics," the veteran says.

Then you have "the structure guys," as the City veteran calls them. They're the ones who actually put together the financial products that are based on the models developed by the quants; the City veteran was one of them. After the structure guys come the traders, who buy and sell the various elements in the packages the others have devised and assembled. "The traders manage the risk," the veteran says, "and they tend to have similar backgrounds to the quants." Very broadly speaking, the quants work in the financial equivalent of an ivory tower to develop models for instruments they think will work; the traders report the results from the trenches, and the structure guys figure out solutions and improvements. And finally there are the salespeople, who may not know much about the math, but know how to talk a persuasive bottom line.

The danger in this juxtaposition of mathematical theory and multiple billions of dollars should be evident to anyone who has ever heard of Murphy's Law. And yet it may not be so obvious to traders in the middle of the action as they implement the quants' models. In fact, their world can be simultaneously very high pressure and almost mystical. "The richness of math is in the abstraction," El Karoui told a science publication for women in 2008, after the crash. "It allows you to take a step back from reality, and that gives us the freedom to think the way we want. Mathematicians display a great deal of imagination."

The traders, the structure guys, and the quants have all seen the numbers sort themselves out before, and they may be tempted to imagine they'll see it happen again this time. The outside world hears only about the derivatives that go wrong, while careers are built on the ones that go right. That's how things have gone in the past, anyway. At JPMorgan Chase, hundreds of billions of dollars were in play, and Iksil was part of a unit that had earned $5 billion in the last three years. Given the extent to which teams are involved in the work of refining and improving the products, the idea that a "rogue trader" can make billion-dollar bets all on his own is, to say the least, improbable. It's worth noticing that other heads besides Iksil's are rolling already at JPMorgan—and they're not French.

And what about the French veteran of the City? He shrugs. "As the derivatives market is declining, you have less interest in these French mathematicians," he says. For his part, he's moved back to Paris. He may soon think about teaching.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.