It's going to take some getting used to: viewing Cézanne's The Card Players to the sound of a mosque's call to prayer; visiting a Rothko after a trip to the souk; scoping a Hirst beside women in abayas. And soon, maybe, admiring the Nordic vision of Munch's The Scream by the light of the desert.

On the evening of May 2, one of the four versions of Munch's painting is being auctioned at Sotheby's in New York. Insiders expect that the Persian Gulf state of Qatar, buyer of Cézanne and Rothko and Hirst, will be aiming to add Munch to that list. Flush with oil and gas, Qatar has the world's highest per capita income, so the world's second most famous painting—after the Mona Lisa—could yet become its most expensive.

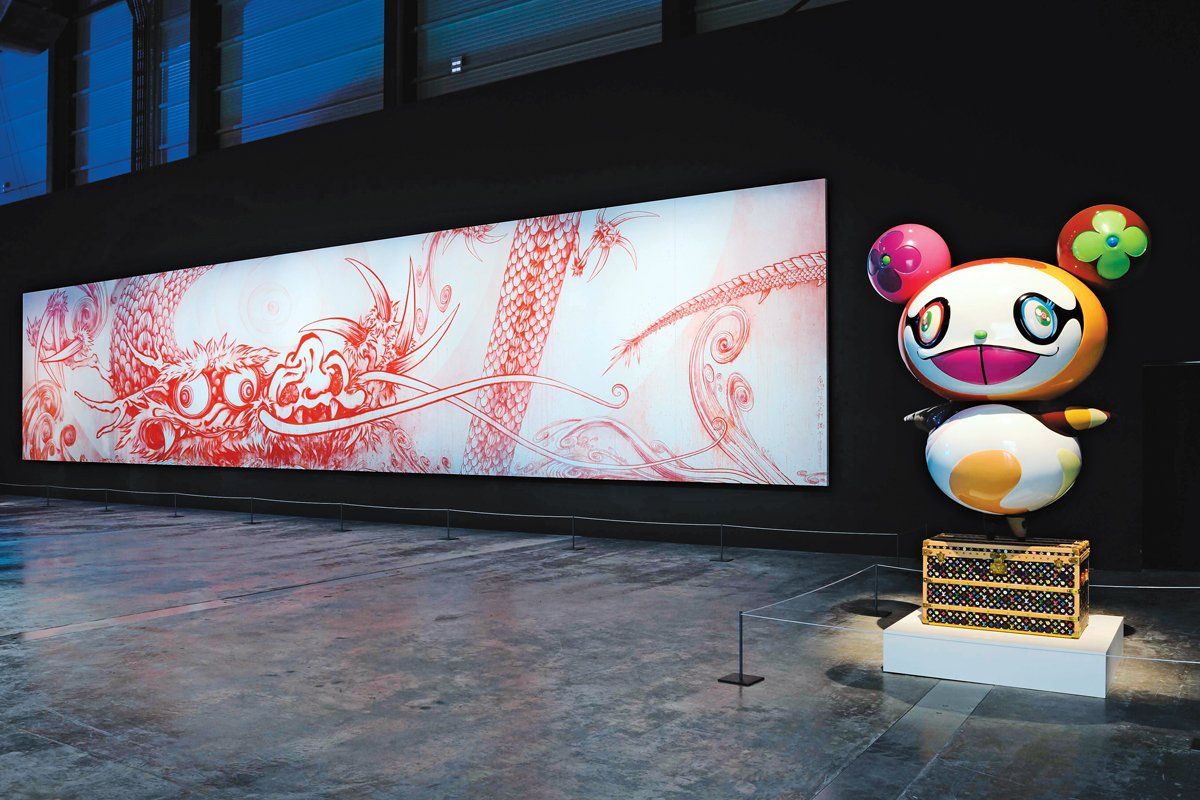

For that to happen, The Scream would have to beat the quarter-billion dollars Qatar already spent on its Cézanne, according to reports in The Art Newspaper. That was almost twice what anyone had ever paid for a picture, while Qatar's Rothko seems to have cost it $70 million, and its Hirst was priced at $20 million. (The Qatar Museums Authority–or QMA–which is in charge of art in the country, does not comment on its purchases, but has also not denied any of these widely cited numbers.) The QMA helped finance the huge Hirst retrospective that just opened at Tate Modern in London, and which travels to the Gulf in 2013. It also put together the deluxe Takashi Murakami survey now hanging in Doha, Qatar's capital, in a building the size of an aircraft hanger. Ducking in for shelter from the Arabian sun, I felt culture shock, cubed: some of the most cryptic, most urban art there is—Japanese cartoons injected with a hint of horror—was being offered to a desert people who owned barely anything a generation or two back, when they started pumping oil.

"If you are a rich country, why wouldn't you create important cultural institutions?" asks Jean-Paul Engelen, as we walk through the Murakami show that he oversaw. Engelen is an auction-house veteran who recently took charge of the QMA's exhibitions and public projects. He says that the royal family—especially the emir Sheik Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani and his 29-year-old daughter, Sheikha Mayassa, who heads the QMA—sees art as "an important part of educating the people of Qatar." He denies the charge that it's about impressing the rest of the world: "I wouldn't be here if it were about bling-bling." Given how hard the royals clamp down on news of their spending—ask a money question, and Engelen might as well have his mouth duct-taped shut—ostentation can't be their principal fault.

Engelen opines that "lack of education, lack of communication, and fear of the unknown is the source of much of the evil in the world," and sees the QMA as lined up against all three. "To build a contemporary art culture in a region that had very little experience of that ... if it happens, it's pretty amazing—you're part of history," he says, explaining his willingness to remain in a place that's still raw. (A thousand skyscrapers bloom; sidewalks are in short supply, as is some nice cold beer.)

When the Smithsonian Institution was established in Washington in 1846, it was aimed at "the increase and diffusion of knowledge" across a crude and newly rich land. The al-Thanis seem to be aiming for their own Arabian Smithsonian. (One difference: the Smithsonian was chartered by an elected government; the QMA's projects come from aristocrats who hardly canvass their citizens, let alone the foreign workers who make up much the nation.)

So far, the QMA's centerpiece is the deluxe Museum of Islamic Art, which a nonagenarian I.M. Pei came out of retirement to build. It opened in 2008, with a permanent collection that "rivals any in the world for sheer quality," according to Michael Barry, an Islamic scholar at Princeton. At its feet is the hangarlike box where Murakami is now showing, and where other blockbusters will follow. Out on the city's edge, there's Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, which currently houses a huge survey of the Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang, famous for his fireworks but here also showing new Arab-themed sculptures. (One is a stuffed camel hanging mid-air, being strafed by stuffed hawks.)

A National Museum to showcase local history and culture will occupy a flying-saucer building underway from Jean Nouvel, while a photography museum is in the works to house one of the world's great collections of historical prints. (Anthony Bannon, director of the great Eastman House photo museum in Rochester, N.Y., has heard that the Al Jazeera network, founded by Qatar, might house its archives there.) Museums of sports and science are also to come, as well as a museum of Orientalist art—all homegrown, unlike the branch-office Louvre and Guggenheim museums coming to Abu Dhabi.

This still leaves us with the $64,000—or $250 million—question: where will we go to see Qatar's Cézannes and Rothkos and Hirsts, as well as Munch's The Scream if it joins them? So far no one is talking. "When we know where we are, and we're achieving it, that's when we announce," says Engelen. All we know for now is that the collections are likely to focus on modern works. A leader in the auction world says that the al-Thanis are avoiding "fussy, old-fashioned pictures" in favor of 20th-century holdings that will be "spectacular, and on par with their Islamic collections."

An emir may find it easier to buy great art than to get his subjects to care about it. The Murakami show was absolutely empty on the Wednesday I went. The Arab modern art museum gets a trivial 1,700 visitors each month. Even in Pei's jewel box, a visiting show of Islamic treasures seemed sparsely attended.

QMA spokesman Omar Chaikhouni describes the al-Thanis' artistic projects as about "spreading a culture of appreciating knowledge, respecting art ... There is no museum culture in Qatar." Creating such a culture is barely a rounding error, costwise, in their vast effort to build a fully modern society that can survive the day when fossil fuels are replaced by some other form of energy.

"Their strategy is not about building something quickly, for now," said one auction-world source. "It's a millennium project ... It's for the next generation."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.