When the 2009 autopsy report on Michael Jackson listed the cause of death as "acute propofol intoxication," his fans were not the only ones who wondered why he was being given this powerful intravenous anesthetic to sleep, as his physician—Conrad Murray, now on trial in Los Angeles for involuntary manslaughter—said. Propofol is not a sleeping aid; that's "not even in the ballpark of appropriate use," says anesthesiologist Beverly Philip of Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston. But propofol has another property that experts are only beginning to focus on: it has a signifi cant potential for recreational use and abuse. "It's not a narcotic like heroin, and doesn't get you high," says anesthesiologist Ethan Bryson of Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. "But it does provide the feeling of oblivion or being spaced out ... And there is an association between having a history of sexual abuse and seeking the escape that propofol provides."

Jackson, who was acquitted of charges that he sexually abused a child, had said his father abused him physically and emotionally. If you wanted to draw any inferences regarding Jackson's use of propofol and sexual abuse, it would be abuse that he suffered as a child and not perpetrated on another as an adult, says Bryson.

As a general anesthetic, propofol acts on the brain's GABA receptors, which cause inhibitory neurons—those that quiet other circuits—to fire; that's how it induces unconsciousness. Propofol also increases levels of the feel-good neurotransmitter dopamine, triggering a sense of reward not unlike sex or cocaine. Some patients experience euphoria, sexual disinhibition, and even hallucinations, followed by a feeling of calm and an upbeat mood. Since propofol is so widely used—it revolutionized ambulatory anesthesia, allowing a physician to knock someone out in seconds to perform, say, a colonoscopy, and have them up and about after only 10 minutes—scientists have had no shortage of subjects able to describe the experience. About one third don't remember a thing, and another third say they dreamed, but don't recall specifics. The rest experience "vivid, strange dreams, sometimes of a sexual nature," says Bryson.

Once propofol wears off, some patients report feeling well rested, energetic, and happy. Murray said he gave Jackson propofol because the singer wanted to feel energized for rehearsals, but propofol does not provide a restorative sleep; anyone using it regularly could become dependent on the drug to function.

Soon after the drug was introduced in 1989, reports of abuse surfaced—all among medical professionals. Since propofol is not a controlled substance like morphine, hospitals tend not to keep it locked up, making it fairly easy for someone to swipe. Reports of such cases appeared as far back as 1992, when an anesthesiologist was found to be self-injecting 10 to 15 times a day. Abuse has since spread. A 2007 survey of academic anesthesiology departments found that 18 percent reported propofol abuse by physicians or nurses—a 500 percent increase from 10 years earlier.

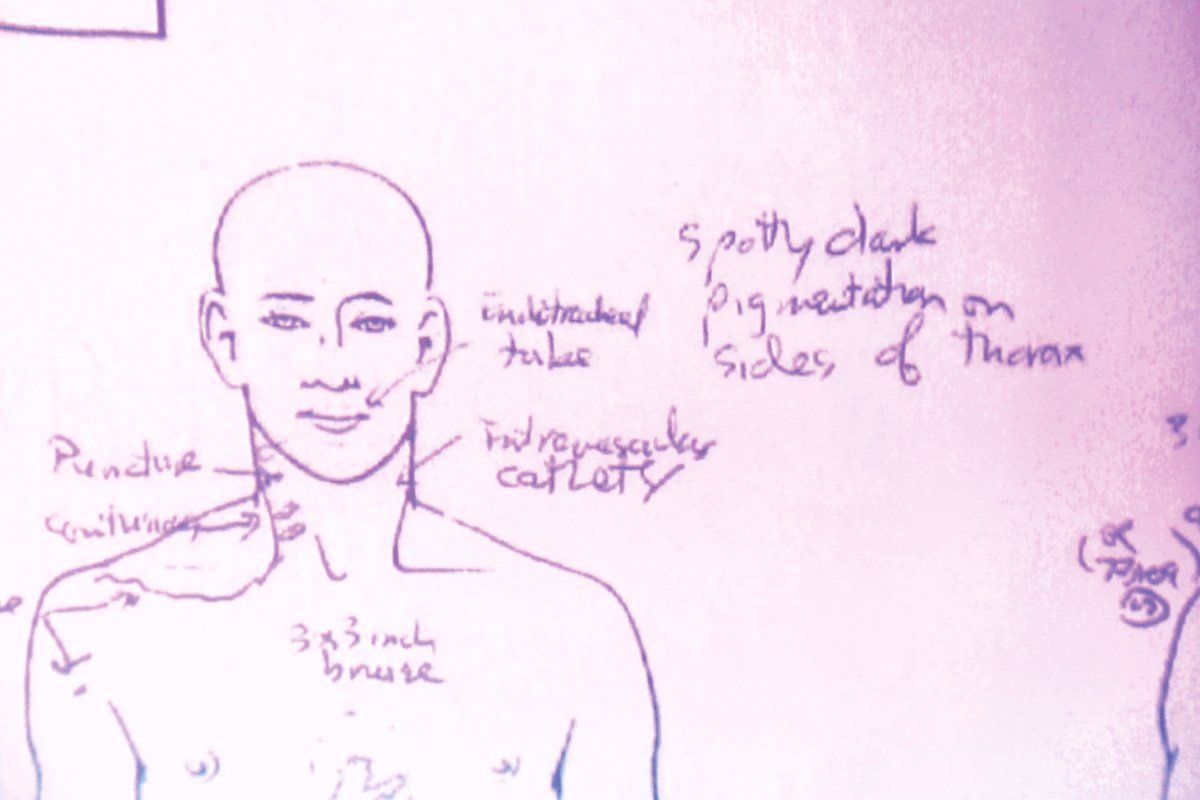

As for patients, some "like it and want to know what it is," says Bryson. "People who have no history of drug-seeking behavior." Physicians are reporting more cases of laypeople becoming addicted. One man who was given propofol for headaches liked it so much he managed to obtain the drug from veterinarians; he was found unconscious after an overdose. In 2009 a woman was found dead in her home, killed by propofol; a friend who was an ICU nurse had access to the drug. Upward of 30 percent of abusers eventually die from using propofol, says Dr. Kenneth Pauker, president of the California Society of Anesthesiologists. In Jackson's case, propofol caused cardiac arrest. Unlike other anesthetics, it has no reversing agent, and there is no straightforward way to rescue someone who takes too much. That helps explain why, in a study of 25 people abusing propofol, seven died. Last year, alarmed by the growing abuse, the American Society of Anesthesiologists formally endorsed a proposal by the Drug Enforcement Administration to classify it as a controlled substance. No action has been taken.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.