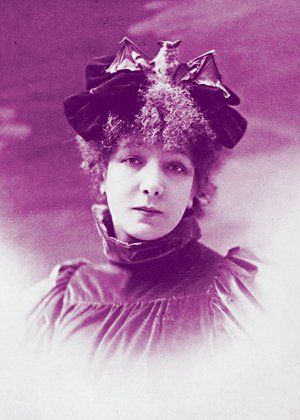

It's tempting to think that the gossip magazines and Web sites, the starlets and the heiresses, all the pieces of the modern celebrity machine, refine their dark arts over time. But they don't. Next to Sarah Bernhardt, our celebrities and the people who make a living off them look like so many pale knockoffs—like yokels.

Much of what the great 19th-century French actress did would be outré even now. She kept a coffin in her bedroom and rewrote fashion's rules: she sometimes wore a hat crowned by a stuffed bat. Her private zoo, parts of which followed her on her many trips around the world, included an alligator, a cheetah, a monkey named Darwin, and a boa (until it swallowed some cushions and had to be shot—by her). One of her many lovers was Proust's model for Charles Swann, another helped to inspire Dracula, and the emperor of France was likely a third. When she visited the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, her curtsy was cut short. "No," said the tsar as he lifted her up, "it is we who must bow to you."

Bernhardt captured the world's imagination because she had a flair for self-promotion—Henry James called her "the muse of the newspaper"—but also because she was a genius. As Robert Gottlieb recounts in Sarah, his immensely entertaining new biography, she didn't just out-Gaga Gaga, she out-Streeped Streep. She brought to the stage a revolutionary naturalism that was more vibrant, modern, and dynamic than the usual declamatory style. Her roles proved as distinctive as the rest of her choices. She played Hamlet when she was 56 and Joan of Arc as a great-grandmother. When her company took The Merchant of Venice on a tour of America, she alternated Shylock and Portia. That actually happened.

Though Bernhardt's life was messy and colorful enough to fill out a massive biography, Gottlieb's is modest, in both length and tone. Much of his work here lies in sifting through Bernhardt's version of her story, discerning what really happened amid her "obfuscations, avoidances, lapses of memory, disingenuous revelations, and just plain lies." Faced with a life as improbable as hers, he shrewdly relies on testimony from contemporary witnesses. To watch her play Phèdre, Lytton Strachey wrote, was "to plunge shuddering through infinite abysses, and to look, if only for a moment, upon eternal light." Offstage, one of her lovers reached an eerily similar verdict about their sex life, reflecting that the days she spent with him "were like pages from immortality. One felt that one could not die!"

The book avoids falling into adulation partly because of Gottlieb's wry but affectionate skepticism of Bernhardt, and thanks to the delightful voice of her friend turned nemesis Marie Colombier. Part Salieri, part high-school mean girl, Colombier dished in a tell-all book about Bernhardt's habit of extracting money from her male devotees by seeming to develop a tubercular cough. (Actually, she was pricking her gums with a needle so she appeared to cough blood.) Their feud built to a majestic finale: when Bernhardt decided she had had enough of her rival's sniping, she showed up at Colombier's apartment, drove her off with a bullwhip, and trashed the place.

Whether it's true or not—and Gottlieb acknowledges that in many, many cases it's impossible to say—a dozen episodes like this one bear out her motto, "Quand meme," which he translates as "even so," "despite everything," or "against all odds." This ferocious determination to rise above her lowly roots (she was born about 1844 to a courtesan), combined with Gottlieb's habit of referring to her as "Sarah," brings to mind a celebrity from our own time who shares that name. Palin, like Bernhardt, is an outspoken, photogenic, envelope-pushing woman who seeks refuge in the flag. During the Franco-Prussian War, Bernhardt turned a theater into a military hospital, risking her life for her beloved France. "I am an actress, a mother, and a patriot above all else," she said.

Bernhardt worked as long as she lived, and lived long enough to see herself challenged by actresses even more naturalistic than she was. In a landmark review, George Bernard Shaw compared her unfavorably with her Italian rival Eleonora Duse. But Bernhardt—who, in the words of a friend, "took herself for granted as being the greatest actress in the world, as Queen Victoria took it for granted that she was queen of England"—found a subtle and characteristically delicious way to save her amour-propre. When Duse dared to perform one of her signature roles in Paris, a reporter asked Bernhardt what she thought of the upstart. "One of the best," she said with a smile.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.