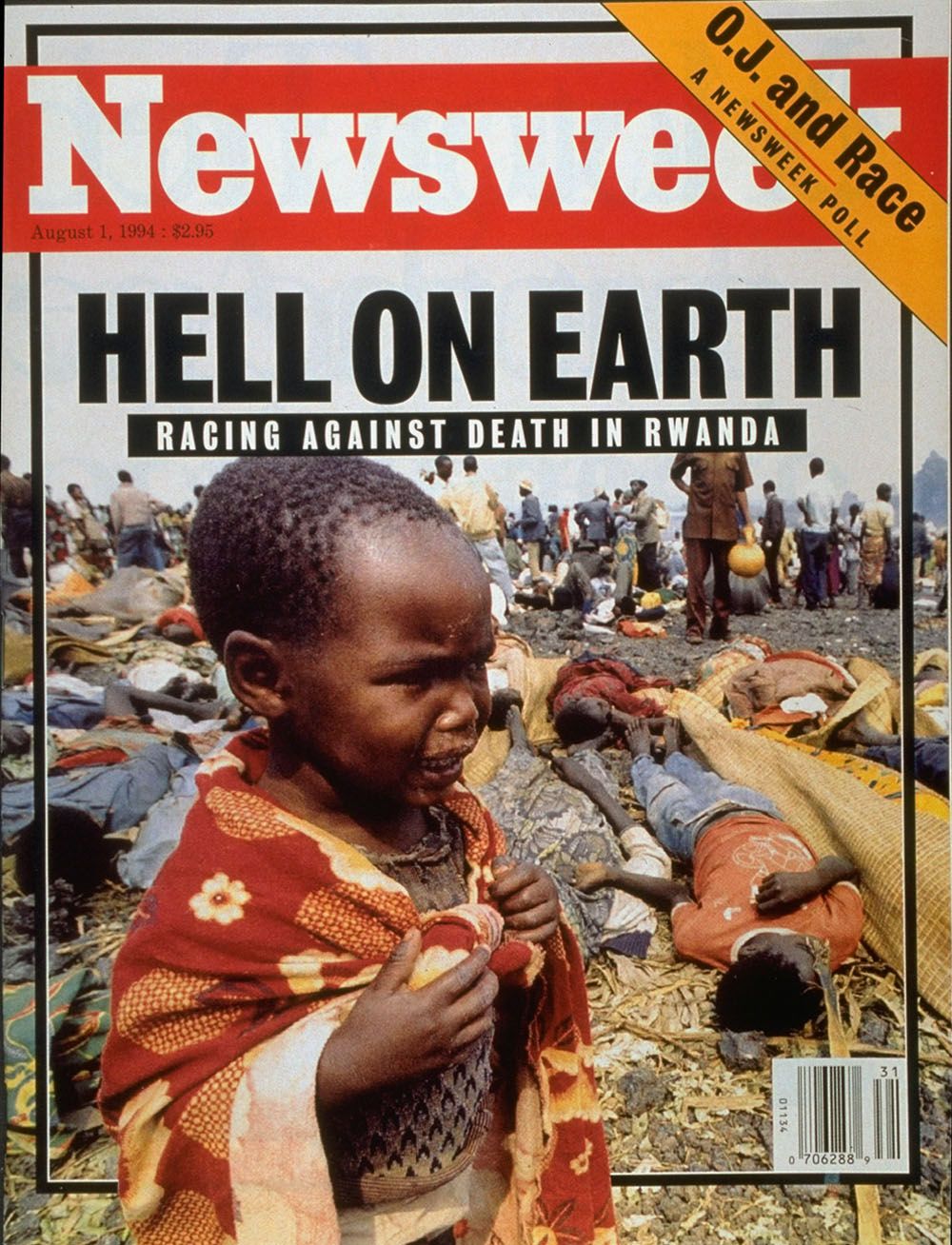

On Monday, Rwanda marked the 20th anniversary of the genocide that eventually claimed the lives of over 800,000 people, mostly members of the country's Tutsi minority. They were slaughtered in some of the most brutal ways imaginable. "The killers were both soldiers and civilians. Often they weren't satisfied with merely killing their victims. Witnesses said the preferred method was to cut off body parts one at a time or to slice bellies open, leaving the victims to die in slow agony," a Newsweekarticle from April 24, 1994, reported. Stark images of corpses—near a church, on the street or in a horrifying jumble—accompanied Newsweek's coverage of the unfolding mass murder.

One story in particular stands out: It's the narrative of one man, Gérard Nshogoza, who had lost everything, only to find some consolation in reuniting with his 4-year-old daughter, Zita. Joshua Hammer, who covered events from Rwanda for Newsweek, reported on the man's saga in our June 27, 1994, issue. The 800-word dispatch captures the madness and horror of the genocide—and a tiny moment of hope—better than any statistics can.

"I've Lost Nearly Everyone"

By Joshua Hammer

Of the dozens of suffering people I've met covering the massacres and civil war in Rwanda, Gérard Nshogoza is the one I'll always remember. I first encountered him on a cool dawn two weeks ago in Kigali, the Rwandan capital, as bursts of mortar and machine-gun fire signaled the start of another day of killing. Moments before I started a journey to the front lines of western Rwanda, he slid into the back of my Isuzu Trooper without any explanation, sandwiched between my rebel escort and an AK-47-clutching bodyguard. I simply assumed he was an official from the Rwandan Patriotic Front who was joining his comrades for an inspection of the battle zone. But when we stepped out to stretch our legs beside a muddy river, Gérard began to tell me his story.

"I've lost nearly everyone," he said, his voice a soothing baritone, his handsome, bearded face an oddly impassive mask. Gérard, 37, was a Tutsi customs inspector and government opponent whose family had been wiped out—about 40 people in all. He'd heard that his 4-year-old daughter had survived, and he had made arrangements with my escort the previous night for a lift to Nyanza, where she was last seen. Our journey over the next 48 hours brought home Rwanda's genocidal madness as no body count could ever do.

Gérard had seen the holocaust coming. Three times in the past year, Hutu militiamen, known as interahamwe, broke into his home in Kigali, beat him and threatened to kill him, he told me. Last February he sent his 29-year-old pregnant wife, a teenage son from a previous liaison and two young daughters to live with his parents in Nyanza, 40 miles south of Kigali, where he thought they'd be safe. "I was wrong," he said bitterly. He was working late in his office near Kigali's Parliament on April 6 when he heard about the president's assassination on the radio. Gérard took refuge in a hotel nearby, listening as interahamwe destroyed the hotel generator and rampaged in the streets outside. The next morning two Malawian U.N. soldiers hid him under blankets in their jeep and drove past militia checkpoints to the national stadium. Gérard eventually made his way to the rebel-held provincial capital, Biumba. He waited there for eight weeks, cut off from any word of his family's fate.

As the rebels advanced to the north and west in early June, a driver who had traveled through the region gave Gérard the terrible news, pieced together from his surviving grandparents and other witnesses: Government soldiers in Nyanza had hacked his wife to death as she walked from her obstetrician on April 15. Then they broke down the door of the family's house and shot his 62-year-old father, mother, three elder brothers and 14-year-old son. (His wife's entire family was also slaughtered.) A Hutu nursemaid had passed off his 2-year-old daughter as her own child and disappeared with her into a displaced persons' camp. And 4-year-old Zita had escaped from the killers by hiding in a banana field for four nights. She was rescued by an Italian priest from the local orphanage. The day before the rebels seized the town, 12 drunken soldiers broke in, lined the children against the wall and threatened to shoot them. The priest fended them off with bribes of radios, cameras and cash. On June 5, the child's great-grandparents—who had survived by hiding in a hospital—retrieved her.

Nyanza was a shattered ghost town when we arrived around midnight, after a 12-hour drive over twisting dirt roads. In the moonlight, Gérard gazed grimly at the smashed windows and rubble-strewn street. "Everything destroyed," he muttered. We slept on flea-infested mattresses in an abandoned schoolhouse. Machine guns fired in the distance.

Before dawn, Gérard ventured into the now deserted town center to fetch Zita. Hours later, he reappeared, carrying a thin girl in blue jeans with huge brown eyes who hugged him tightly. Gérard had found Zita with his grandparents at the hospital, where she was still recovering from a chest infection and two months of terror. "She had lost her voice but regained it when she saw me," he said, betraying uncontrollable emotion for the first time in our journey. "She is traumatized, but starting to smile."

Heading back up north, we passed long lines of refugees and truckloads of fresh recruits singing victory songs on their way to the front. Gérard had given up trying to find his other daughter; the region around Nyanza was still filled with interahamwe, and it was impossible to move freely. For now, all his energy was focused on Zita, who had emerged from her terrified silence and begun to murmur softly to her father. Arms clasped around her, he said, "She is a consolation for everyone I've lost." They caught a lift on the road to Biumba, survivors alone in a world without mercy.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Rob Verger is liaison to Newsweek’s foreign editions and also reports, writes, and edits. In addition to Newsweek and its ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.