Could a George Bernard Shaw play, annotated with invisible ink, have been used by Japanese living in America at the beginning of World War II to send coded messages back to Japan? This was one of the paranoid assertions of a document called the Dies Report, made public in February of 1942 — just months after the attack on Pearl Harbor — that asserted that Japan could be planning a U.S. invasion, from the West coast moving east, and aided perhaps by intelligence provided by people of Japanese descent living in the States. The report was mentioned in Newsweek at the time, noting that the 285-page document had surfaced just before the U.S. government was "preparing to move all Japanese, citizens as well as aliens, out of Pacific Coast 'combat zones.'"

Last week marked the 72nd anniversary of the beginning of that dark chapter in our history. On Feb. 19, 1942, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an Executive Order paving the way for people of Japanese heritage, both U.S. citizens and not, to be moved into internment camps. More than 120,000 people would eventually be forcibly relocated from their homes, businesses, and communities into 10 camps.

Paranoia compelled some Americans to be eager to make this happen. Newsweek reported at the time that people in coastal areas "were more anxious than ever to get rid of their aliens after rumors that signal lights were seen before submarine attacks" off Santa Barbara and Los Angeles.

The policy was by no means greeted with unanimous support. A column in Newsweek in March of 1942 carefully discussed the arguments for and against the relocation, saying that opponents of the move protested that American citizens would have their rights violated. Another argument against the move was an inconsistency in policy: Japanese Americans were not being forced to relocate from Hawaii, a "vulnerable area" which had been hit by the attack on Pearl Harbor a little over three months earlier; and there had been no acts of sabotage. The response to that argument, presented at the time, is that it would be impractical to move Japanese Americans from the Hawaiian Islands, and the fact that there had been no sabotage yet implies that it could come later—a dubious line of reasoning asserting that because something hasn't happened yet it is more likely to happen later.

The opponents of the policy were aware of the bad optics, internationally, too. If Japan was making World War II "a racial war," the nations opposed to it "cannot stand for white superiority." Our "battle cry must be 'democracy,' with all that it implies as to equality," Newsweek said, paraphrasing the reasoning of those opposed to the relocation. In other words, how can we wage a moral war overseas if we're oppressing a certain ethnic group at home? And besides, as this line of reasoning went, Japanese Americans could be helpful in the war effort, possibly in espionage or propaganda. (Indeed, Japanese Americans did serve in the war, providing valuable assistance in combat and in intelligence and linguistic work.)

And yet these arguments were mooted, because the relocation happened anyway. As for the consequences? "At best it will leave wounds," the column reflected. At worst, the cost could be "the permanent alienation of a group of citizens" who might have been useful to the U.S. in the war.

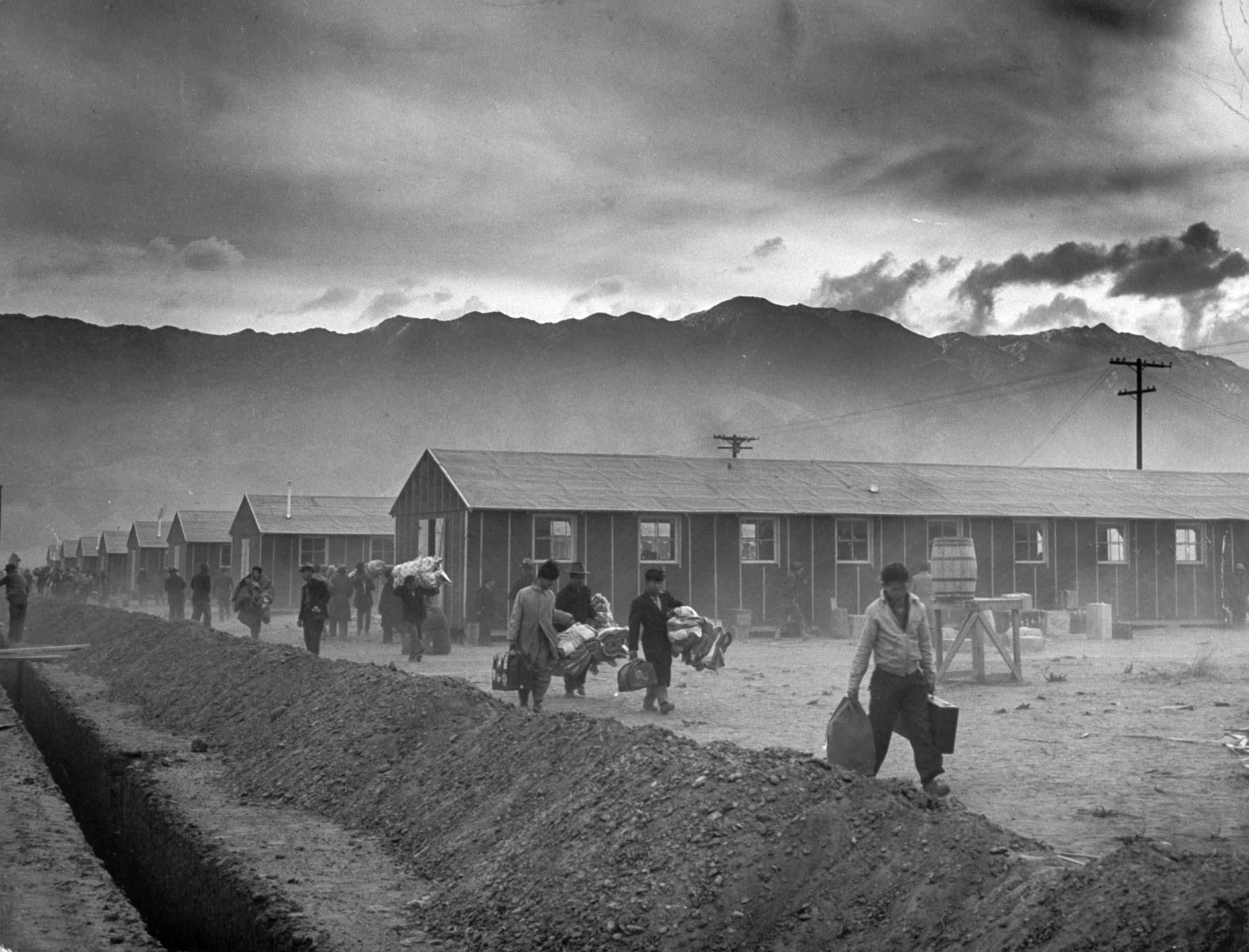

The next week's issue chronicled the first stages of the relocation in a matter-of-fact article titled "Japs Transplanted." About 500 Japanese Americans gathered in the Rose Bowl stadium in Pasadena, California, on March 23, 1942. They were the first wave of "the greatest forced migration in American history," as Newsweek described it. From there, with soldiers accompanying them, the men, women and children traveled 235 miles to the "windy Owens Valley." In a camp built by the Army they would be "put to work digging irrigation ditches and growing crops for their own subsistence."

Seventy years later, in 2012, author and Newsweek contributor Julie Otsuka wrote an evocative, melancholy essay on her family's internment at the Topaz Camp in Utah during World War II. It's the details she presents that make the piece so vivid: the way on her mother's last day of school before being relocated her mom recalled that "the whole class had to say goodbye to me." Or the way they were brought there on a train with its windows blacked-out, or that in the winter the temperatures dipped to minus 20, or that the camp was ringed with "barbed wire fences and armed guards." And then there's the heartbreaking fact that her uncle, then 8, had brought a canteen along, thinking "he is going to 'camp.'"

"I think on some deep level it's something that I'm clearly obsessed with," Otsuka told Newsweek, when asked how the legacy of her family's internment had affected her. Her family dealt with that period with "a lot of silence," she says, which compelled her to try to get to the bottom of what had happened. She talks about anger and sadness in her family, and the fact that those emotions were repressed, which "was very cultural." She added: "Just as a strategy for survival, most Japanese Americans after the war just tried to kind of get on with things, and not really look back."

Newsweek, in 1942, wondered what the cost might be. I asked Otsuka what she thought the ultimate cost might have been—although it might be an impossible question to answer. "On one level, I think that Japanese Americans were so eager to be accepted, that in many ways maybe they would not let their rage get the better of them. But it is a hard question to answer, because I feel like people had so many different responses to that experience... Some people remained deeply bitter till the end of their lives. Some people were able to put it behind them." For just her own family, the cost of internment "was economically devastating."

"That generation was deeply, deeply, alienated," she added. "This was not what they expected of America. And yet, on another level—not a big surprise—it's also the culmination of decades of racism."

"They had been alienated already, for a long time, by the time they were sent away."

The issue came up again recently, when U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia was asked about a related Supreme Court decision in Hawaii while teaching a class. "It was wrong," he said, "but I would not be surprised to see it happen again, in time of war. It's no justification, but it is reality."

U.S. Internment of Japanese-Americans in WWII

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Rob Verger is liaison to Newsweek’s foreign editions and also reports, writes, and edits. In addition to Newsweek and its ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.