To be honest, it's not an ad that puts you in the mood for a burrito.

The spot for Chipotle Mexican Grill starts bleak and gets bleaker: the story of a farmer who becomes Big Agriculture, maltreating his pigs and polluting the water as winter descends. It's long, at two minutes and 20 seconds, and told entirely via stop-motion puppetry. There's no dialogue, only the spooky crooning of Willie Nelson. And the Chipotle logo appears just once, at the very end, on a truck pulling away from a farm returned to its roots, chickens pecking freely in the sun.

At any number of companies, the ad would have been killed for any number of reasons. It's unfunny. Political. Expensive to air.

There was also a chance that it was brilliant. So Mark Crumpacker, a career creative director who now heads the company's advertising efforts, uploaded the video to YouTube, rather than gambling on a pricey TV buy. He watched as the clip quietly but steadily went viral. The band Coldplay, whose track "The Scientist" Nelson covered in the ad, told its 18 million Facebook fans to take a look. Twitter buzzed. Food blogs, then music blogs, then advertising blogs all chirruped their approval. The message worked after all: Chipotle cares about sustainable farming.

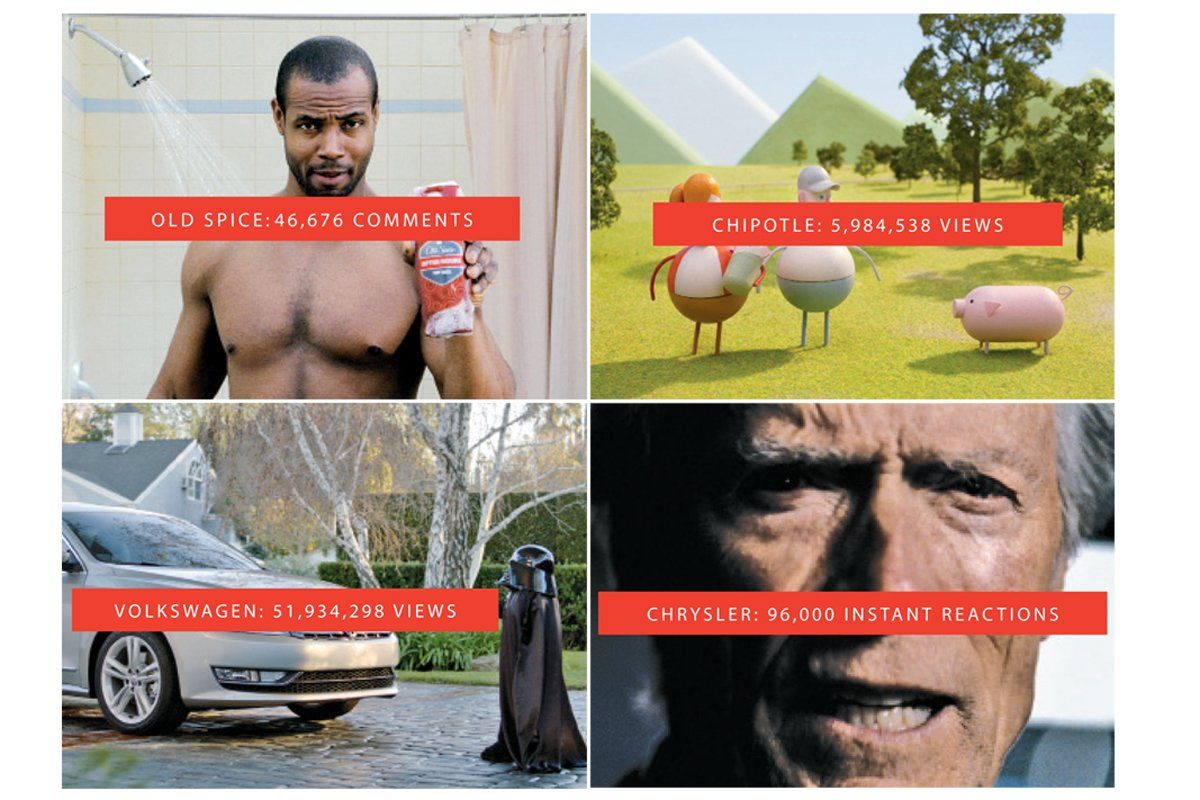

Encouraged by the online response, Crumpacker ran the ad, titled "Back to the Start," in movie theaters nationwide. Field researchers brought back tales of audiences bursting into applause. YouTube views climbed past 5 million. All of this led, last month, to the burrito chain buying the first national TV time in its 18-year history. And during a Grammy Awards watched by 39 million people, the critical response was unequivocal: Chipotle's ad stole the show.

Unorthodox as it is, Chipotle's spot can be seen as a template for the future of great advertising. Ignoring conventional wisdom about what works in which medium—jokes on TV, wordplay in print, cats on the Web—the company focused instead on a single, piercing idea that works on all of them. And by using the Internet as a platform for testing worthwhile work, not just zaniness, Chipotle took the risk out of a risky piece of marketing.

Time was, advertising was a relatively simple undertaking: buy some print space and airtime, create the spots, and blast them at a captive audience. Today it's chaos: while passive viewers still exist, mostly we pick and choose what to consume, ignoring ads with a touch of the DVR remote. Ads are forced to become more like content, and the best aim to engage consumers so much that they pass the material on to friends—by email, Twitter, Facebook—who will pass it on to friends, who will ... you get the picture. In the industry, "viral" has become a usefully vague way to describe any campaign that spreads from person to person, acquiring its own momentum.

It's not that online advertising has eclipsed TV, as some industry pundits have predicted, but it has become its full partner—and in many ways the more substantive one, a medium in which the audience must be earned, not simply bought. Going viral is no longer a lucky accident or fringe tactic, but the default expectation of any ambitious campaign, on any platform.

"If it goes viral, it's ratification of it being good 'creative,'?" says Crumpacker, 49. "And if it doesn't, you're like, 'Oh, God, what did I do wrong?'?"

The global advertising industry is estimated at $500 billion, and if you are a human with the capacity for thought, you are aware that most of it is dreck. The ads that do break through the flood tide of pablum come, more often than not, from a shifting handful of hot agencies—the Sterling Cooper Draper Pryces of today. Some, like Wieden + Kennedy, have led the "it" list of creative firms for years; newer shops, like Droga5, Mother, and Johannes Leonardo, climb on or fall off based on their ability to convince clients that they can navigate the fractured way Americans consume media today. That means the best agencies of 2012 are obsessed with making campaigns—whether for Fortune 500 accounts or upstart brands—that get ratified online.

For a decade, viral was the province of weird stunts (like SubservientChicken.com, for Burger King's customizable sandwiches) and downmarket brands. No longer. When the most shared ad of 2011 is a Super Bowl spot by Volkswagen, clocking 52 million YouTube views, it's safe to say that viral is not a fringe part of the industry.

"Viral has moved from being sort of this niche tactic, into something that's more of a statement about what all advertising should be. And that is, something that people actually seek out and want to share," says David Droga, the creative chief of Droga5, in his Manhattan office. The digital age's answer to Don Draper, the native Australian has won awards for selling—really—tap water. His agency's clients range from Microsoft to obscure hummus concerns; its work spans all media, from print to TV to billboards, but all of it relies on catching fire online.

Take the agency's work for Prudential. How do you make ads for retirement planning—a numbing topic in a crowded category—stand out? Droga's approach is to nail the idea, then pick the medium. First, the creative team jettisoned the usual images of hot older actors playing golf and smiling at charts, and sought out actual retirees—people with wrinkles, fears, and hopes. Hundreds of them sent Droga5 pictures of their first day as pensioners, which the agency used to create a national TV spot. Next came a Web site and mini-documentaries about individual Prudential customers, which have been viewed nearly a million times online. Last month, the nonprofit organization TED named the "Day One" campaign a winner of its "Ads Worth Spreading" contest.

The scale of success that the right idea can have online can be difficult to fathom. Consider 2010's Old Spice sensation, created by Mark Fitzloff and Susan Hoffman at Wieden + Kennedy, which started as a typical TV campaign but exploded as viewers sought it out on YouTube. "The Man Your Man Could Smell Like" mostly defies description, but it involves a towel-clad man with great pecs and better elocution who maintains intense eye contact with the camera while holding an oyster shell full of diamonds that morph into "two tickets to that thing you love" and, eventually, Old Spice body wash. Yes, it's silly. But the campaign caused sales to spike 107 percent. Follow-up clips, in which the character responds to individual YouTube commenters, drove the brand's total views on the site to more than 279 million. That's just shy of the viewership of two and a half Super Bowls.

There are many ways to measure virality and zero agreement on what constitutes success. Ad agencies will brag that a client's microsite has reached viral liftoff if it has 500,000 Facebook likes—or 50,000, or even 10,000. Two YouTube clips, one with 1 million views, the other with 10 million, are both certified contagious. It's all highly arbitrary, with one consistent rule: if a campaign doesn't pass the magic threshold, it is considered to have something seriously wrong with it.

Sharing Is Caring: Ad-making people are an expressive bunch, and so the fact that virtually everyone I spoke to repeated a certain phrase—over and over again, like they'd all read the same talking-points memo—seemed to indicate two things. It's big. And they haven't quite figured out what it means. "Advertising," they all said, "is not just a one-way street anymore."

After decades of advertisers blaring messages at consumers, those consumers now have their own megaphones to blare back. "Before you could have written a letter and said, 'My Glad Wrap doesn't work, and you suck,'?" says Cal McAllister, a tousle-haired co-founder of the Seattle agency Wexley School for Girls. "But it's not like putting that on your Twitter feed, if you have a million followers."

Radio, digital, above-urinal signage—it doesn't matter. Regardless of where a piece of advertising appears, social media is now the place where consumers react. If motivated, they can seize a brand and reshape its image at a pace that obliterates even the best-planned marketing strategy. For the first time, companies are no longer the sole owners of their own brands.

To longtime ad strategists, this is scary. But the scariest things, once harnessed, can also become the most powerful—particularly when the medium is digital. If an advertiser rolls out a campaign that encourages consumer response, and consumers respond with derisive stuff that starts to go viral itself, it's a PR disaster. But if consumers embrace the idea, it can defibrillate even the most listless of brands—like Skittles, whose "Taste the Rainbow" slogan was jolted awake with a series of offbeat videos by TBWAChiatDay.

Managing this—a sort of planned digital epidemiology—has become an essential offering of any competitive agency. Most now employ "community managers," whose function, despite the boring job title, is to obsessively track social networks; when a client's brand is spiking they'll spotlight favorable stuff (perhaps by circulating upbeat blog items), and they'll try to extinguish anything that makes the client look bad (zapping through an instant refund to an angry tweeting customer can help). Their stethoscope is extraordinarily sensitive. "We have won and lost business based on a single tweet," says McAllister.

The casino allure of social-media advertising is a lucrative specialty for a young set of all-digital agencies. The problem with giving yourself that label, though, is like the old Abraham Maslow maxim: if all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. When Jan Jacobs and Leo Premutico started their agency, Johannes Leonardo, in 2007, they took pains to emphasize that they were not just another digital shop. "This was confusing clients for a decade: 'What do I give digital agencies? What do I give traditional agencies?'?" says Jacobs, 41 and scraggly, over breakfast one morning in New York. "There's a breed of modern agencies that we'd like to think we're a part of, that don't really think about things like that. Because if you're a purely digital agency, then you start approaching the problem thinking the solution has to be a digital one." The pair, a former Saatchi & Saatchi creative team, try to resist the platform of the moment, in favor of declaring consumers themselves the medium. Four years in, their clients include Coca-Cola, Google, Bacardi, Chanel.

One of their most telling campaigns, for discount clothing chain Daffy's, involved hiding a borderline-pornographic image in plain sight—pieces were scattered across 40 different posters in New York City subway stations. Commuters reassembled them on Twitter to get the joke: a randy couple had taken off the clothes they'd bought at Daffy's, where you get "More Bang/Less Buck." Crude, but it actually gibes with Johannes Leonardo's lofty theory. "If you create a piece of work that resonates with the consumer, you can see an outdoor advertisement become a digital work, because the consumer is the one who takes it from one medium to another," says Premutico.

Thinking like this can unite a small shop like Johannes Leonardo with a much bigger one, like the billion-dollar Martin Agency. Headquartered in Richmond, Va., Martin contains much of the industry's past—and its future. It was one of the agencies that proved, in the 1970s and '80s, that top-level work could be found away from Madison Avenue; its greatest feat was turning a small regional insurer named GEICO into a national power, with the help of a spokes-gecko and a pair of politically correct cavemen.

"The word 'advertising' is starting to get kind of old. We do ads, obviously, but we do so much more now," says John Norman, Martin's chief creative officer. With torn jeans, chin-length rocker hair, and a charcoal Armani scarf knotted thickly at the neck, the 45-year-old looks more like someone playing a creative director in an ad than the real item. "We used to tell stories through campaigns. And now we build stories. You set something out there in the ether, and people start to build on it or add to it or take away from it, and it becomes a bigger story."

They're Gr-r-eat!: Advertising is said to exist at the intersection of art and commerce. And there are a lot of high-speed collisions at this intersection.

Creating breakthrough advertising is long, discouraging, bleary, quarrelsome work, until it is joyously complete. And then, often, the client says, "No, too strange, too risky." This conflict between the brilliant creative director and the stodgy business folks is as old as the industry; it's a repeated plotline on "Mad Men" and happens every day in the real world.

"A lot of brands are most comfortable with sure mediocrity," says Wexley's McAllister. His agency—whose offices appear from the street to be a Chinese restaurant—specializes in creating weird stuff for major clients, like a recruitment campaign for Microsoft that involved Jacuzzis, sandwich boards, and a sizzling bacon cart. "Everyone is looking for a guaranteed batting average. They don't care if it's high or low, they just want to be able to plan around a .270 hitter. The upside is it's easier for agencies like us to be entertaining and break through the clutter and create captivating advertising. That lets us swing for the fences."

Digital technology, the destroyer of so much of the industry's infrastructure—newspaper ads, the 30-second TV spot—now provides a chance for more advertising to be what it has so seldom been: good. TiVo gave us the joy of fast-forwarding through crappy 30-second spots, but YouTube gave us the ability to call up the spots we like.

"It changes the fundamental role of the ad, from something that's secondary into something that has to be primary," says Andrew Essex, Droga5's CEO. "The ad in an ironic way becomes more like content—it has to be 'good.' It has to be interesting, it has to be shareable, it has to make people say, 'Oh, I liked that.' Advertising ... [It] can't be about bombarding people with pollution anymore."

The advertising industry, it turns out, had turned into one of those brands that needed defibrillating. And the shift is turning out to be good for brilliant creative directors and stodgy business folks alike.

"Traditionally conservative companies are willing to be a little more risky now and try ideas they wouldn't usually go for," says Gerry Graf, who founded the agency BFG9000 and whose past clients include Procter & Gamble and Mars (those ingenious Skittles ads). "Think of P&G 10 years ago. Now they're the company that OK'd the Old Spice campaign. That's a huge change."

The creative minds on the precipice of joining the industry like the sound of that. Virginia Commonwealth University, in Richmond, is home to the Brandcenter, one of the best graduate programs for advertising in the country. Often referred to as a "portfolio school" or "finishing school," it teaches students who may have minored in communications or art history how ad agencies actually work. Students with a degree from here are highly sought after by the planet-size firms in New York, like BBDO and McCann Erickson; the students, in turn, lust after jobs with the smaller hot shops of the moment: Wieden, Droga5, Mother, BFG9000.

The Brandcenter's brick building is a 19th-century carriage house, whose inside has been renovated into a sleek creative space with open floor plans, clever coursework hanging on the walls, and an Apple-product-to-student ratio approaching 3:1. One morning in January, 40 students, average age 25, average shirt color plaid, are attending the semester's first meeting of Digital Portfolio, a class that will help them build personal websites to showcase their amateur work.

But they put that aside to talk about their hopes for their careers. They want to create work, they say, that rates with the hall-of-fame stuff by Apple and Nike, to have "the ability to make something that's different and inspiring." At all costs they want to avoid "hack work"—"stuff that's been seen before or copied or repeated or cliché. Anything that disappoints."

It's not clear to me what that means, so I ask for examples. Jeff Vitkun, 25, has a ready response: "Just turn on the TV." Classmates nod.

OK, then—so where can you find the good stuff? "Have you ever gone on YouTube and watched a commercial?" asks Jon Ransom, 27. "Like, intentionally, to see that commercial?" Sure: the Old Spice guy. Nike's stuff from the NBA lockout.

"If it's something you would go to see," he says, "then it's probably good."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.