On a nondescript block south of New York's Union Square, up a dreary staircase and through a black-barred gate, there is a long, narrow room that might be mistaken for a very small museum of literary counterculture. On one wall hangs two rows of iconic posters: Paul Davis's print of Che Guevara's proud head; a photograph of the authors Jean Genet, William S. Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg marching at the 1968 Democratic National Convention; a portrait of Bobby Kennedy. Loose-leaf binders of correspondence with groundbreaking authors line floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. Beside the bookcases, Samuel Beckett peers out of a black-and-white photograph with a fierce crow's gaze. Next to him in the picture stands a shorter, milder-looking man named Barney Rosset.

Rosset's publishing house, Grove Press, was a tiny company operating out of the ground floor of Rosset's brownstone when it published an obscure play called "Waiting for Godot" in 1954. By the time Beckett had won the Nobel Prize in 1969, Grove had become a force that challenged and changed literature and American culture in deep and lasting ways. Its impact is still evident—from the Che Guevara posters adorning college dorms to the canonical status of the house's once controversial authors. Rosset is less well known—but late in his life he is achieving some wider recognition. Last month, a black-tie crowd gave Rosset a standing ovation when the National Book Foundation awarded him the Literarian Award for "outstanding service" to American letters. This fall, Rosset was also the subject of a documentary, "Obscene," directed by Neil Ortenberg and Daniel O'Connor, which featured a host of literary luminaries, former colleagues and footage from a particularly hilarious interview with Al Goldstein, the porn king. High literature and low—Rosset pushed and published it all.

On a recent afternoon, Rosset sat on a worn leather couch with a book of Beckett's and a binder of his letters with the Nobel laureate. He was working on his autobiography, "The Subject Is Left-Handed"—a title taken from his FBI file, which his wife, Astrid Myers, was paging through at a small table nearby. Rosset has been working on the book for years. "I don't know what the publisher wants," he said. "No idea. Been in the same job for many years—I think I would have known better."

The story of Rosset's life is essentially one of creative destruction. He found writers who wanted to break new paths, and then he picked up a sledgehammer to help them whale away at the existing order. "He opened the door to freedom of expression," said Ira Silverberg, a literary agent who began his career in publishing at Grove. "He published a generation of outsiders who probably said more about American culture than any voice in the dominant culture ever could." A Grove book, said Robert Gottlieb, who served as editor of Simon & Schuster and then Knopf during the years Rosset ran Grove, "made a statement. It was avant-garde. Whether European or American, it had very special qualities; it was definitely worth paying attention to." Through Grove and its offshoot, a literary magazine called Evergreen Review, Rosset was a curator and a self-styled rebel. He published whatever he liked, even (or especially) when it got him into trouble. "I think he was at his best, enjoying life, when we were in crisis," says Richard Seaver, who was, with Fred Jordan, a top editor at Grove.

Rosset saw many crises. He or his company was forever going broke, being attacked, breaking the law. In his legal battles, Rosset made his most enduring impact. Before Rosset challenged federal and state obscenity laws, censorship (and self-censorship) was an accepted feature of publishing. His victories in high courts helped to change that. Rosset believed that it was impossible to represent life in the streets and in the dark recesses of the heart and mind honestly without using language that in the mid-20th century was considered "obscene"—and therefore illegal to sell or mail. To a significant extent, the books he published convinced others that this was true.

Rosset wasn't the only publisher who took risks, but he was one of the most visible and uncompromising. Not everything he published was high-minded. Some of it aimed below the belt, and he was uncompromising about that too. His stubbornness made his achievements possible, but it also helped to undo him. At the end of the '60s, Grove moved into fancy offices, into film, and, to some extent, away from books. The repression of the '50s and freewheeling openness of the '60s were over, and other houses, now free from fear of censorship, took more chances. The left splintered. The feminist movement attacked him. Grove began to drift. But Rosset, as always, kept doing what he wanted, everything else be damned.

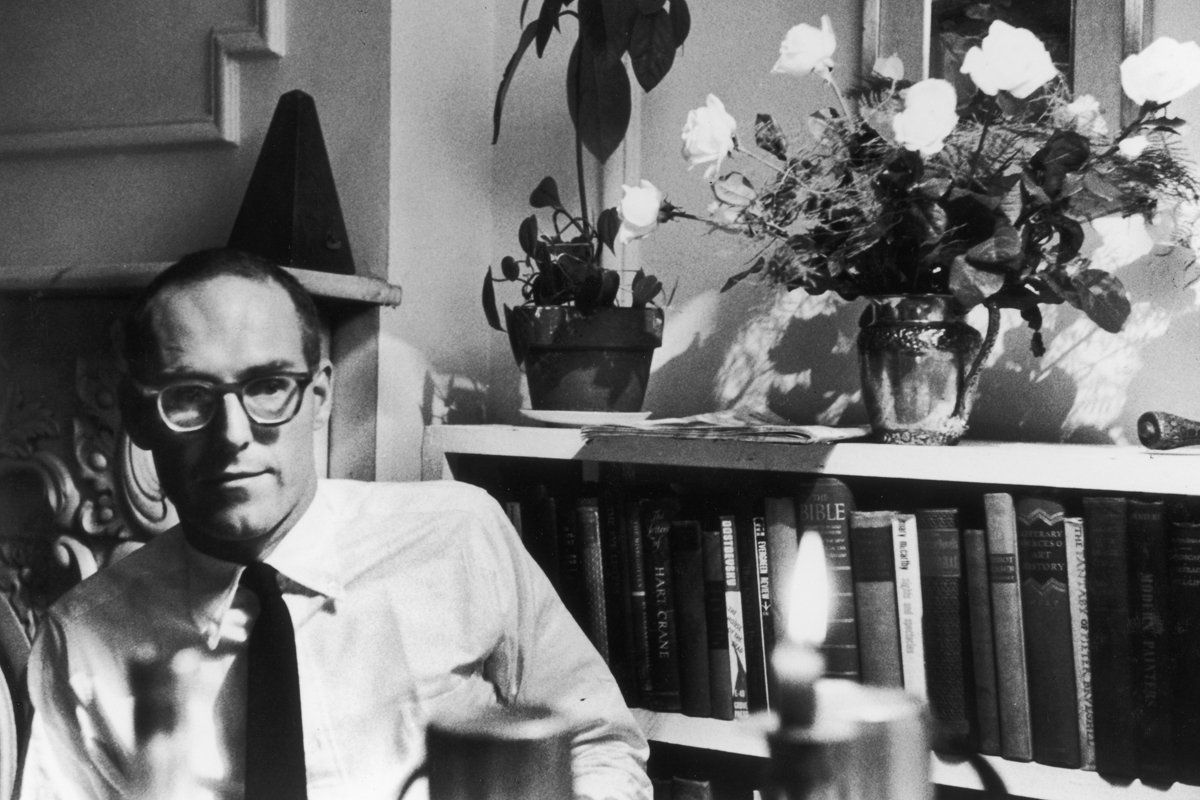

Rosset is now 86. Small and slight, with thinning, cropped white hair, bright blue eyes behind black-framed glasses, and wearing jeans held up with navy blue suspenders, he seems surprisingly boyish. As he slouches on a couch below a psychedelically painted wooden carving of a dragon, clutching a cup of Coke (with rum) in his right hand, it's easy to imagine him as a 12-year-old kid. That was about the age that Rosset began his career as a troublemaker. Born in Chicago in 1922, the only son of a wealthy banker, he was an unlikely but fervent radical. In school he and his best friend, Haskell Wexler (now an Academy Award-winning cinematographer), produced a paper called "Anti-Everything" and joined the American Student Union. "We mainly worked together on trying to marry the same girl," Rosset said. She chose Wexler.

Around this time, when Rosset was at Swarthmore, he came across "Tropic of Cancer" by Henry Miller, which had been banned in the United States for its graphic descriptions of sex and prostitution. (The copy Rosset bought, at the Gotham Book Mart in New York, was smuggled in.) To Rosset, though, "Tropic" was about the dissolution of a romance. The narrator "felt he wanted to die," Rosset says. "And then, being the selfish person he was, he pulled himself out of it, and said, 'I'll go on'." Inspired, Rosset jumped on a bus and headed for Mexico, chasing a bohemian lifestyle. He got as far as Florida. These were itinerant years for Rosset. He bounced from college to college and from the infantry to the Army's Signal Corps in China during the war. He produced a movie in New York and then followed another girlfriend, Joan Mitchell, to Paris, where they married. Back in New York, Mitchell,a stormy and beautiful painter, introduced him into the Greenwich Village scene. The marriage quickly fell apart—"Joan hated everyone," Rosset said admiringly—but one day a friend of hers told Rosset that a small press on Grove Street was for sale. Rosset bought it for $3,000.

Rosset cut an unlikely figure for a publisher. He was a 29-year-old senior at the New School (his fourth college), and his favorite book was banned. In those days publishing was considered a "gentleman's profession"—ascots, discretion, dynasty, martinis. Rosset wasn't interested in any of that (except the martinis). He wanted to disrupt the existing order, and he wanted to publish "Tropic of Cancer." But as late as 1953, a high court affirmed a customs ban on the book, so, for once, Rosset knew he'd have to be patient. He began publishing out-of-print books while looking for something new. Before long, he'd found Samuel Beckett.

In their early correspondence, Beckett mentioned a concern to Rosset: there were, in his works, "certain obscenities of form which may not have struck you in French as they will in English," which he thought could cause legal problems. Rosset replied, "Sometimes things like that have a way of solving themselves." He had no interest in letting challenges come to him. "Barney chose these battles," said Peter Mayer, who ran Avon and Penguin during Rosset's time at Grove. "There was nothing inadvertent in what came down." In its first year after Grove's publication, "Waiting for Godot" sold fewer than 400 copies. It has now sold some 2 million.

Censorship had been a feature of American society since the Puritans landed at Plymouth, but it wasn't until the late 19th century that a postal inspector named Anthony Comstock and his Society for the Suppression of Vice successfully lobbied to restrict what could be sent through the mail. "Serious" literature wasn't exempt, and for the most part publishers didn't test the laws. There were exceptions. Most notably, in 1933 Random House sued to import James Joyce's banned "Ulysses." Federal courts ruled in its favor, finding that though individual passages were obscene, the book as a whole lacked "the leer of the sensualist." "Tropic of Cancer" was the screed of a sensualist, though, and so Rosset knew he'd have to find a way to stretch the law.

In 1954, Rosset received a letter from a Berkeley professor, Mark Schorer, urging him to publish a banned, unexpurgated version of "Lady Chatterley's Lover." (Knopf had already published a censored version.) Rosset didn't love the book, but he thought it could be a steppingstone to "Tropic." He moved strategically—publishing an essay by Schorer in the first issue of his new Evergreen Review, and Allen Ginsberg's "Howl," banned in San Francisco, in the second. Then Rosset published "Lady Chatterley's Lover." In 1960, a federal court of appeals overturned the ban of the book on the ground that the centrality of vivid depictions of sex did not itself create obscenity.

"It was a very exciting, febrile time," said Richard Seaver, who joined Grove as an editor just before the "Chatterley" court case. "Lady Chatterley's Lover" was a bestseller, and Rosset was already preparing to publish "Tropic." But first he had to convince Henry Miller, who feared that the attention would compromise his outsider status. "I said, 'No! That's ridiculous'," Rosset said. "I believed it at the time. I couldn't quite see that we ourselves would push, push, push to get it to be a textbook—and succeed." Miller only agreed to sell the rights after his Parisian and German publishers interceded.

When "Tropic" was finally published, the lawsuits crashed down in waves. Rosset and Miller themselves were charged in Brooklyn for selling and conspiring to sell an "obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, indecent, sadistic, masochistic, and disgusting book." In Chicago, when a prosecutor accused Rosset of being motivated only by greed, Rosset pulled out a college term paper he'd written on Miller and began to read it aloud. Finally, in 1964, the Supreme Court ruled—without briefs or arguments—that "Tropic of Cancer" was not obscene because it had social value.

As usual, Rosset was already charging ahead. Burroughs's "Naked Lunch," with incendiary portrayals of homosexuality and drug use, came next. The assault on conventional morals continued with books by John Rechy, Hubert Selby Jr., Jean Genet, and Pauline Réage, whose sadomasochistic "Story of O" had scandalized even Paris. "We did almost a yearly bombshell," said Seaver. "Barney loved— I won't say he loved the litigation, but he loved everything that went with it." The trials were expensive, but the books were selling. By the mid-'60s Grove found that it could—by virtue of its own success, as well as shifting mores—be profitable and still be disreputably renegade. The new cool was democratic and expansive. It was anticapitalist, but it liked the things money could buy. The books mattered more than the parties, but the parties mattered too—and Rosset threw some good ones. Lennon partied with Mailer; painters mingled with poets. Beckett was baffled by Burroughs when Barney introduced them, but on the Grove list they coexisted easily. Prudery and repression were alive and well—rebellion needs its enemy—but there seemed to be a widening sphere in which experimentation was possible and even lucrative. Rosset took advantage.

Grove was picking up writers from around the world. The Evergreen Review, which began as a quarterly in a trade-paperback format, expanded its reach. Edward Albee published his first play in its pages. Susan Sontag's "Against Interpretation" appeared there. Frank O'Hara, Franz Kline, Tom Stoppard, and scores of other writers and artists contributed, many of them early in their careers. Meanwhile, Grove was becoming more political—not just in its defense of freedom of expression. After Malcolm X was assassinated and Doubleday scuttled his autobiography, Grove snatched it up. When Che Guevara died, Rosset entered the hunt for Che's diaries—prompting anti-Castro militants to bomb the Grove offices with a fragmentation grenade. (In the movie "Obscene," Rosset tells the story with obvious delight.) This wasn't the only time Grove or Rosset was a target for violence. Around the time Valerie Solanas shot Andy Warhol, she was spotted lurking near Rosset's office with an ice pick.

The dangers were real, but they increased the sense of adventure. "It made the work more exciting to know that you were pissing off a lot people," said Nat Sobel, a Grove executive. It was the '60s, and politics and culture were interrelated as never before. Experimentation was the watchword—and not just on the page. Rosset was in the scene but not entirely of it. He invited writers to the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, but he "got scared" and didn't go himself. ("Jean Genet, he was there. He wasn't scared of nothing!" Rosset said, pointing to the poster of Genet, Burroughs and Ginsberg, which had been an Evergreen cover.) Rosset took amphetamines but freaked out when Timothy Leary gave him LSD, hallucinating that one of his ex-wife's paintings was attacking him. He was trying to reconcile the romance of the desperado with the imperatives of his job. "We were not totally deaf to commerce," said Seaver.

Inevitably, with commercial success came increased commercialism. Evergreen Review became a glossy (called Evergreen), and in 1968 Grove launched an ad campaign in the subway, urging riders to "Join the Underground." Circulation of the magazine rose from 7,500 in 1957 to 125,000 in 1968 and continued to rise. But Rosset ran his business by instinct, not budgets. He succeeded because he had a sense for both the establishment and anti-establishment, and he was able to make one interesting to the other. "Grove in some ways was a master of achieving attention for their publications," said Peter Mayer, "both outside and then finally inside the main channels." William O. Douglas, the Supreme Court justice, excerpted his memoirs in the April 1970 issue—and so had to recuse himself when Grove went to court to fight a ban on a Swedish film called "I Am Curious (Yellow)." The film—today considered unremarkable soft porn—made millions. Newly flush, Grove bought a six-story building and installed air conditioning, an executive elevator and a front door in the shape of a "G."

The renovation was completed in 1970, and that was the year that Grove began to fall apart. Prompted by the success of "Yellow," Rosset, who had always wanted to be a filmmaker, bought foreign films as fast as he could find them. "Barney was buying the entire output of Czechoslovakia, Poland, God knows, whatever," Seaver said. "None of them worked. Suddenly, all the money we'd made on 'Yellow' was down the drain."

There was the growing sense that Grove had lost its mission. "Things were already beginning to go into a tailspin," said Sobel, who had resisted the new emphasis on film and was fired. "I almost think that Barney fired me to spare me from watching the company that I helped build fall apart." The '60s had ended, and the hope was turning sour. Peaceniks gave way to militants. Grove's move from an upstart house to a media conglomerate made its anti-establishment posture seem more like a contradiction. The feminist movement gained strength, and Grove became a target.

Rosset loves titillating novels, and they held a small but prominent place on Grove's list. Some of these are now classics (like "Tropic") but others (like "Romance of Lust") appealed to crasser sensibilities. Rosset calls these books "erotica." "I once said 'porn' about something he'd published and he just exploded," said Mike Topp, a friend of Rosset's. Whatever the label, the books were considered pornographic at the time they were published. (Now some of it just seems sort of squishy.) In 1969, Life magazine published a profile of Rosset titled "Old Smut Peddler." To some of his colleagues, the erotica was a trade-off that made the less commercial books possible. "The porn greased the wheels there," said Silverberg. "There was always porn on that list. And people actually used to read it." But Rosset bristles at the suggestion of any economic calculation. "The erotica excited me. I liked it. I thought it was sexy. It was just that simple," he says. To feminists, however, it wasn't simple at all.

Rosset had championed the far left since middle school, but there were "some gaps in his progressive program," as John Oakes, an editor who later joined Grove, delicately put it. In early 1970, Rosset fired several employees who had tried to unionize the editorial staff. One of them, Robin Morgan, was a feminist activist, and in April, she and a group of women barricaded themselves in the executive offices. Grove "earned millions off the basic theme of humiliating, degrading and dehumanizing women," the protesters stated. Rosset was out of the country ("in Denmark buying more films," Seaver laughed ruefully), so he and Seaver consulted by phone on whether to call the police. Would Grove really turn the cops on a group of protesters? Finally, Rosset told Seaver to make the call.

"We had always thought of ourselves as liberators," said Seaver. "We all felt we were working for a cause instead of a publishing house." Their blindness left them unprepared. Grove had a masculine ethos and mostly male executives. So did many other houses at the time, but the difference was that Grove claimed to stand for justice, civil liberties and sexual freedom. "Sex and politics go together," Rosset said. The feminists agreed; in fact, Rosset's words sound a lot like their mantra, "the personal is political." But what they meant was that inequality and oppression were prevalent in all aspects of a woman's life, from the bedroom to the boardroom. Rosset meant was that there is no freedom without freedom of expression in all realms.

The protest came at a terrible time for Grove. The real-estate market collapsed, and by the end of 1971, Grove was deeply in debt. It sold its new building at a huge loss and suspended Evergreen. Meanwhile, other publishers were taking advantage of the more permissive environment, and there were fewer untouchable manuscripts. "They had such a distinctive position, particularly in the '60s, as the countercultural publisher," explained Morgan Entrekin, who merged Atlantic Books with Grove's backlist to create Grove/ Atlantic in 1993, several years after Rosset had left. (Grove/Atlantic remains one of the few well-respected, successful independent publishers.) "As they moved into the '70s and '80s other publishers started to occupy the same ground."

Finally, in 1985, Rosset was forced to sell to the oil heiress Ann Getty and the British publisher George Weidenfeld. Rosset believed he would remain in charge. But a year later, on a snowy evening, he walked into the Bar Americain in Paris, where a group had gathered to celebrate Beckett's 80th birthday, and announced he'd been pushed out. Beckett asked what Rosset was going to do. "Start over, I guess," said Rosset. So Beckett gave Rosset one of his early unpublished plays, "Eleuthéria," to help him begin publishing again. But when the playwright set about to translate it from French, Beckett decided that the play wasn't good enough to publish, and sent Rosset a note. "I feel unforgivable. So please forgive me," he wrote. Beckett dedicated his last book, a prose piece, "Stirrings Still," to him.

Under his own imprint, Rosset published "Stirrings Still." But after Beckett died in 1989, he returned to "Eleuthéria." When he tried to hold a reading of the play, Beckett's estate threatened to sue, forcing Rosset to move it from a public venue to his apartment. And when he tried to publish it, the estate resisted— for a while. Rosset wouldn't give up. He also published a few more books, including the Victorian erotica that Grove's new owners had jettisoned, and a book by Kenzaburo Oe, who won the Nobel Prize in 1994. There have been other moments of fight, but it's been a few years since Rosset sued anyone. Now he's working on his autobiography, and producing, with Myers, the Evergreen Review, which was revived online in 1998. He has a blog.

When talking about the major obscenity trials of the mid-19th century, Norman Mailer once said, "There's a wonderful moment when you go from oppression to freedom, there in the middle, when one's still oppressed but one's achieved the first freedoms. By the time you get over to complete freedom you begin to look back almost nostalgically on the days of oppression, because in those days you were ready to become a martyr, you had a sense of importance, you could take yourself seriously, and you were fighting the good fight."

There seemed to be some justice to this comment, and so I asked Rosset what he thought of it. He waved the question away. "That was Mailer! He would have been crazy in any time," he said. And then he launched into another story, about the time Mailer filmed a movie, "Maidenhead," in the Hamptons. Rosset picked up a small wooden block onto which a photograph of his East Hampton Quonset hut had been laminated, and told me about how Mailer had bit off a chunk of an actor's ear while filming at a nearby estate after the actor had gashed Mailer's head with a hammer. "What was his name? Tony?" he asked Myers. (Rip Torn was the answer.) Myers went over to a cabinet of old VHS tapes, took out "Maidenhead," and pulled off the cover. "What a terrible movie," she said, and smiled.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.