It isn't often in this business that you're sitting at your desk and you get a phone call from a source that causes you to nearly fall off your chair. But that's exactly what happened in my office at Newsweek's Washington bureau early on the afternoon of Jan. 13, 1998. "There's a little event going on at the Ritz-Carlton in Pentagon City right now you might want to know about," my (very plugged-in) tipster told me. Linda Tripp was having lunch with her good friend Monica Lewinsky—and Ken Starr had the whole thing wired. Starr?! Yes, my source said: I know it sounds crazy, but Starr (the independent counsel appointed to look into Bill Clinton's Whitewater business dealings) was now investigating the president's relationship with Lewinsky. The lunch was a sting aimed at getting the then-23-year-old former White House intern to flip and cooperate.

I was dumbfounded. I had been talking to Tripp for months—ever since I tracked her down one day at her desk at the Pentagon the previous March. I had heard all about Monica Lewinsky and what she had been telling Tripp about her fling with the president: the late-night phone calls, the surreptitious visits to the Oval Office, the telltale evidence on the blue dress hanging in her closet. It was a surreal story that seemed improbable at first, but more and more credible (and newsworthy) as Tripp offered up more tantalizing details. Clinton was arranging to get Lewinsky a job. He had given her gifts. And, once she got subpoenaed in the Paula Jones lawsuit, he fully expected her to keep her mouth shut, according to Tripp.

But while I had briefed Newsweek's Washington bureau chief, the levelheaded Ann McDaniel, about all of this, neither she nor I were ever clear on how (or even whether) we were going to actually publish any of it. How would we ever prove that this affair actually happened? Or that the president had really told Lewinsky to lie? But the fact that Starr was on the case—that was unquestionably news. The story would turn Washington upside down—and, I immediately knew, would raise as many questions about prosecutorial overreach as it would about presidential recklessness and mendacity. And Newsweek was right in the middle of it. We alone knew what was going on.

What took place over the next few days—as I first recounted in a book some years ago—was a crazy journalistic dash that seems today like a blast from another very distant era. My job was to nail down Starr's involvement, the underlying "crimes" he was investigating, and (there was no way to take this out of the equation) figure out exactly what we could say about the alleged sexual relationship at the center of it. Oh, and to get it all into publishable form in four days, Newsweek's deadline for the next week's issue.

My efforts led two days later to a tense confrontation with Starr's deputies in a conference room in downtown Washington. "Let's face it," one of Starr's lieutenants told me. "You've got us over the barrel." If Newsweek went ahead with this story, or started making some calls to the White House for comment, we would tip off their targets and sabotage an ongoing law-enforcement operation. Could I be persuaded to hold off? I bargained. We could possibly hold off making phone calls for another day. (It was pretty much standard practice at Newsweek to hold off making phone calls to principals on major exclusives until late in the week anyway—to avoid tipping off the competition.) But I needed something in return: to know precisely what had led them to launch this probe in the first place. "Unless you show me what you've got and establish the predicate for this, you're going to get roasted," I told them. They squirmed and didn't give me much of anything. But when I left, I knew we were absolutely on solid ground in preparing a story.

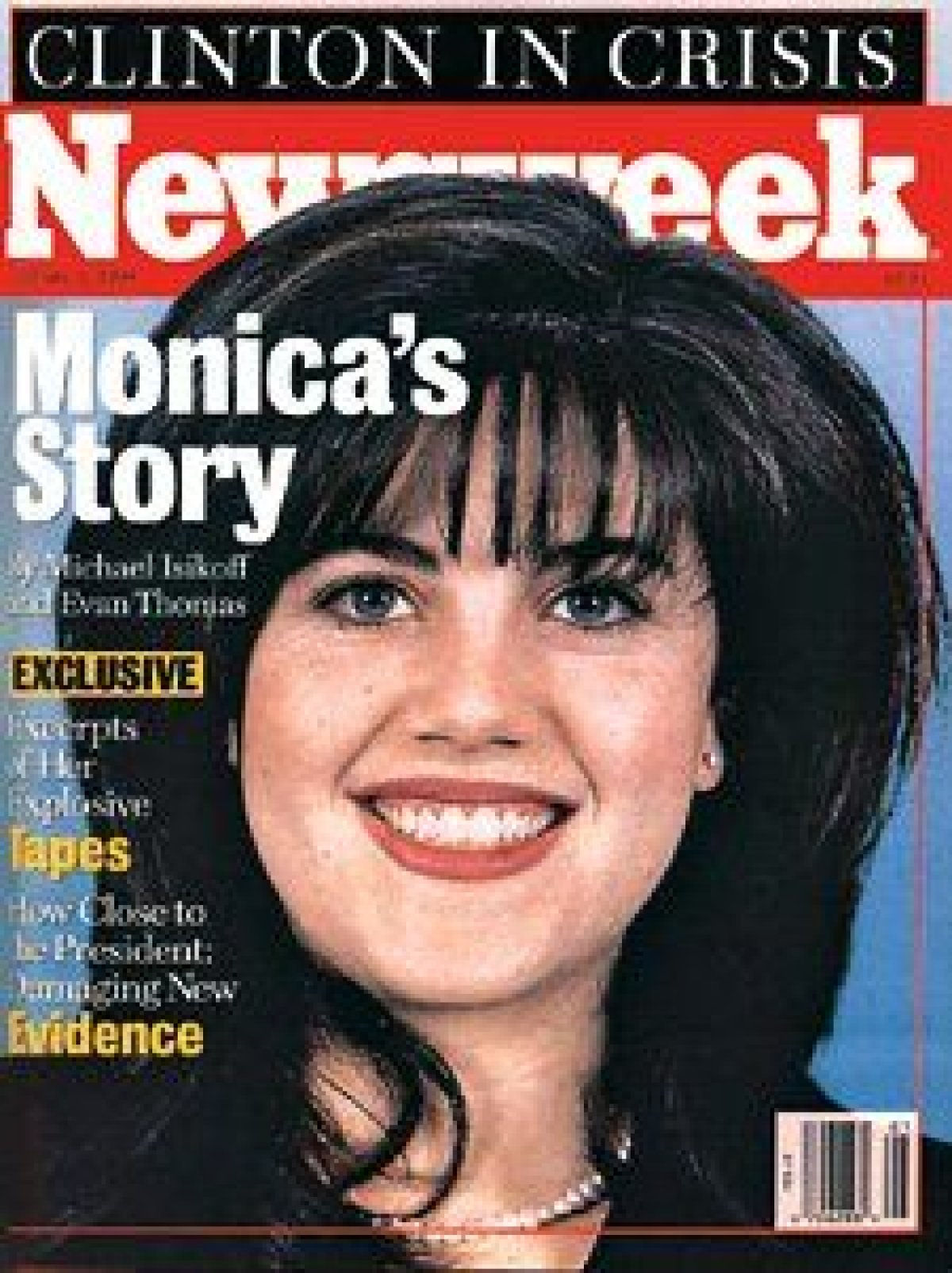

We knew that Tripp had been secretly taping Lewinsky for some time, even as she feigned sympathy for Monica's "plight" (enmeshed in a love "affair" that had zero future, dragged into a lawsuit she wanted no part of). At one point, a few months earlier, Tripp and her "adviser" Lucianne Goldberg had even offered to play one of the tapes for me. Then, I had backed off, fearing I would get drawn into their plots. But now, Newsweek and I definitely wanted to hear those tapes: they were critical evidence in an ongoing criminal investigation targeting the president. After a barrage of backdoor negotiations over ground rules, the tapes arrived at Newsweek's Washington bureau—delivered by Tripp's lawyer—at 12:30 a.m. Saturday. The bureau's team—me, Justice Department reporter Danny Klaidman, and senior editor Evan Thomas—all gathered in McDaniel's office to listen as we parsed every word.

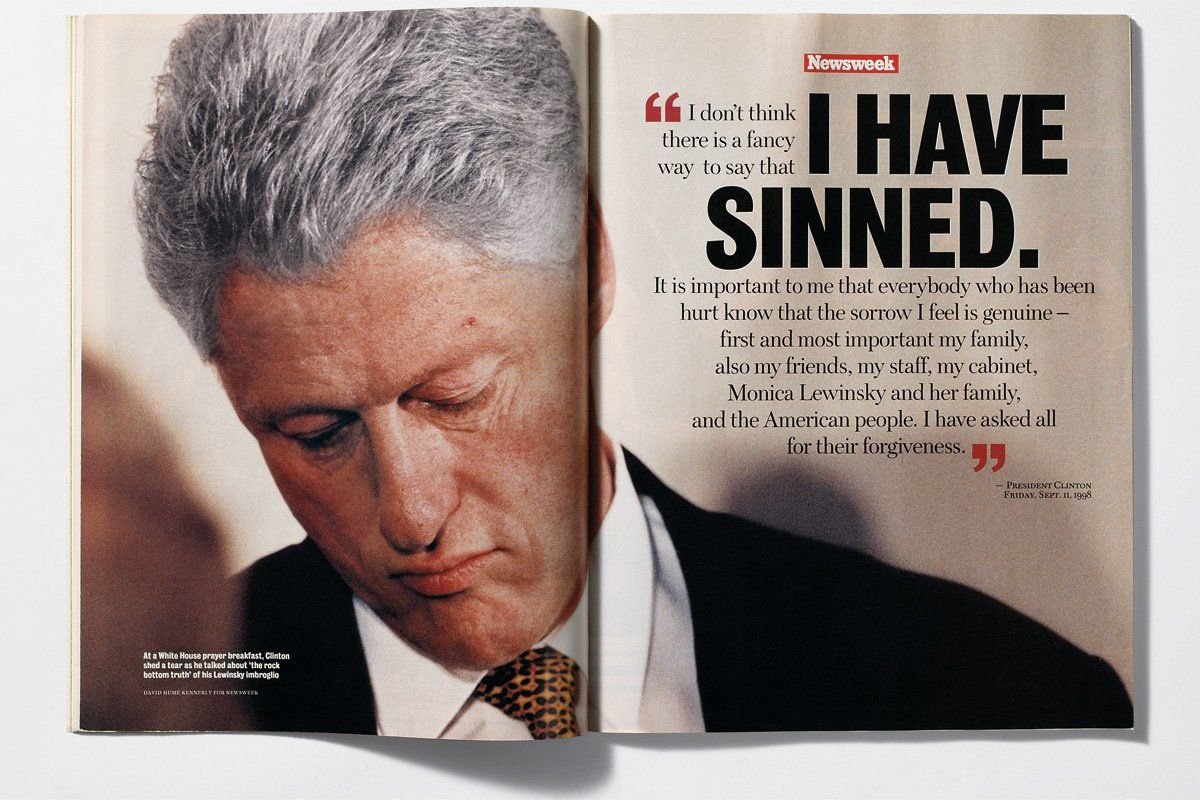

The conversation we heard that morning was for the most part as had been described. Tripp and Lewinsky talked about Clinton, calling him "the big creep." They talked about his gifts to Monica—and how Paula Jones's lawyers would never be able to "prove" anything. "Nobody saw him give me any of those things, and nobody saw anything happen between us," Lewinsky could be heard saying. The affair with Clinton was inferred, but never explicitly stated. More problematic: she never actually stated that Clinton (or his emissary to her, Washington superlawyer Vernon Jordan) had told her to lie in her deposition in the Jones case—the alleged "obstruction of justice" that was the basis for Starr's involvement. "He know's you're going to lie. You've told him, haven't you?" Tripp goads her. "No," Lewinsky replies. A moment later: "Well, does he think you're going to tell the truth?" "No ... oh, Jesus."

A few hours later, we all reassembled—this time with the senior Newsweek editors on speakerphone in New York. What did we have? The bosses were clearly nervous. "Could we really accuse Jordan of suborning perjury without something harder?" asked Rick Smith, the magazine's editor in chief. "Could we really accuse Clinton of an impeachable offense?" Klaidman and I looked at each other and rolled our eyes. "Impeachable?" I thought. What does this have to do with impeachment? It's just one hell of a story—as much about Starr as it was about Clinton, we argued. A little later, Klaidman came back with fresh news. Starr had gone to the Justice Department, and Clinton's attorney general, Janet Reno, had approved a formal expansion of his mandate to conduct the Monica probe. Now Thomas—who had been on the fence—came around. "If we were The Washington Post or The New York Times, we would print," he said. But we were coming up against a hard deadline, and the brass wanted more work. The decision was final: Newsweek would hold the story.

It didn't take long, of course, for it to explode. Early Sunday morning, Internet scribe Matt Drudge popped his screaming "World Exclusive": "NEWSWEEK KILLS STORY ON WHITE HOUSE INTERN ... SEX RELATIONSHIP WITH PRESIDENT." Oddly, no mention of Starr at all. Three days later, The Washington Post had its own banner headline reporting the special prosecutor's investigation. As the truth began to unfold, and Newsweek's insider knowledge became clear, The New York Times asked if I was suicidal when the story was spiked. I don't know about suicidal, I replied. "But I won't deny certain homicidal tendencies." Still, I had a job—and we had a magazine to put out. We published our first account on Newsweek's website Tuesday night. And that weekend, Thomas masterfully weaved our reporting into a riveting cover story that laid out more details than anybody imagined about how the whole strange story had come about, who the characters were, and what was and wasn't on the crucial tapes. It was the ultimate Washington "must read"—and Newsweek went on to win the National Magazine Award (and many other honors) for it. I would have preferred we had it first, of course. But we settled for having it better than anybody else.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.