I first watched Kids the way most 11-year-olds lucky enough to see it in 1996 did: on a worn-out VHS, slack-jawed and with one eye on the door.

The movie struck me as glamorous. There we were, in a second-floor bedroom in a middle-class commuter community in New Jersey, ensconced in safety but also docility. And here was proof that just across the river, real kids more or less our age were steering their skateboards right into the menace and possibility of the world. We probably caught it at just the right time: old enough to understand what was going on, young enough to be impressed by it and gloss over all the film's brutality.

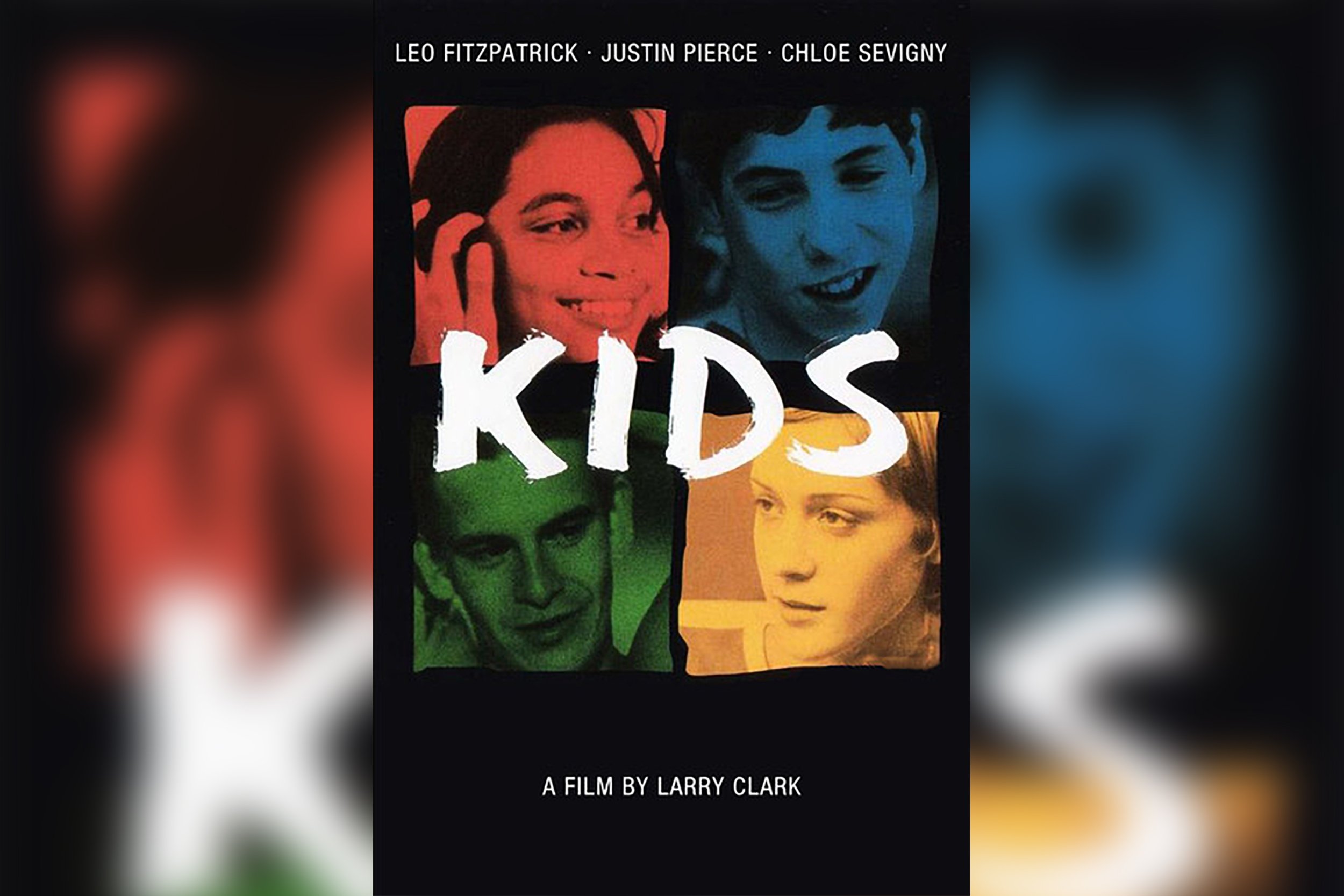

Kids starred mostly amateurs making their acting debuts. Before director Larry Clark plucked him out of obscurity and made him notorious, Leo Fitzpatrick (who played 16-year-old Telly) was just a Jersey kid taking the bus into Manhattan with his board, hanging out in Washington Square. Chloe Sevigny (Jennie) was a teen from a wealthy Connecticut suburb, cutting school and making her way down to Tompkins to sell her knitted hats. Fitzpatrick and Sevigny and Justin Pierce (Casper) and all the others—they looked nothing like the pomaded Freddie Prinze Jrs. or Neutrogena-commercial-perfect Jennifer Love Hewitts of the time. They looked kind of like us. And Clark shot them in a cinema verite style that I somehow remembered as being black-and-white until I rewatched it recently. It's definitely not—it's actually richly colored—but it gives off the impression of grain and grit, from head to toe.

That VHS—stamped NC-17—was an item of totemic value to us, illicitly conjured into being by one of our older brothers and only watched in this one house on these rare nights. By the end of middle school, I'd probably watched it half a dozen times. In the hallways, by our lockers, we would make grisly jokes about the movie: "I have no legs ching, ching, ching, ching," we'd sing-chant in the style of the legless subway beggar who rolls past Telly and Casper midway through the film, making noises meant to replace the jangle of his cup of panhandled coins. "I have no legs." I never could really figure out how to skate—two left feet—but I wore Zoo York T-shirts and listened to the Beastie Boys, just like them.

Two decades later, I saw it on the big screen for the first time. It was, I was told, director Larry Clark's personal 35-mm print. A crowd gathered at the Angelika Theater, the Greenwich Village institution where Kids had its premiere in 1995, and where, around the corner, my father lived when I was growing up. Another audience member afterward waxed nostalgic about how he and his friends snuck into the theater to watch the premiere, sitting on their skateboards in the front by the screen. I remembered seeing a Marx Brothers double feature with my dad and younger brother around that time, the air in the theater pungent with pot smoke. Today, the Angelika is more craft beer than counterculture, with espresso made from fair-trade beans and quiches from Tisserie served in the lobby.

The same year that Kids was shot, Rudy Giuliani was sworn in as the 107th mayor of New York City. He quickly put into place an aggressive "Broken Windows" approach to law enforcement, under which officers cracked down on minor offenses like graffiti tagging, marijuana possession, turnstile jumping, loitering and trespassing. Commissioner Bill Bratton's memos to his deputy commissioners on what to target in 1994 could have formed the plot points for the Kids script.

"If we hadn't shot the movie in 1994, it couldn't have been made," Clark said during a question and answer session after the recent screening. He says he didn't set out to make a documentary. But the legacy of Kids feels very much tied to the veracity of its art, and how, as many reviewers have pointed out over the years, it appears to offer little in the way of diagnosis beyond Clark's loving lens; it opens with Telly deflowering a 12-year-old-girl amid her teddy bears, progresses through moments of senseless violence, bigotry and racism, and ends with one of the most uncomfortable rape scenes committed to film—and yet you still get a sense that these kids are beloved by Clark, and thought beautiful.

Then there's that ineffable energy of being on the edge that permeates the script: The film just barely holds onto a world about to slip away. "It's the last time you see New York City on film like that," said Mike Hernandez, who played himself in the film, and went on to become a pro skater. "It's a New York that's gone."

Kids was the dying breath of a city on the verge of indissoluble change. First Giuliani cleaned the streets, then the planes crashed, and everything changed. It used to be that Washington Square was where you bought weed, the East Village was where you drank forties on the street and Times Square was where you just didn't go unless you were trying to catch that last bus of the night from Port Authority back to Jersey. Now, they all kinda look the same—shiny, clean and tourist-friendly. It's a shock to realize that the entirety of Kids took place in Manhattan, not some far reach of the outer boroughs. Today, the average rent on the island is $4,081 a month. Giuliani and Co. changed the city forever. Crime, according to the NYPD's CompStat reports, has dropped 77 percent from 1993 to 2015, but much of the city's beautiful rough-hewn culture may be gone, too.

Kids "is a New York City frozen in time," said Jeff Pang, another pro skater who played himself in the film. "You don't get to document your life like that." The cast and crew—many of whom, including Hernandez and Pang, participated in the Q&A at the Angelika—were certainly after verisimilitude. Clark had been looking for ideas for a film about adolescents. "The most visually exciting teens were the skaters," he said. "They were so fucking angry. If they didn't have skating, they would have been dead." So he embedded himself with the downtown skate crew, learning, at age 50, how to ride. Then he decided: "I wanted to make a film with kids the same age as the kids I was actually with." So he drafted them all into his army of extras for the film.

"Everything in the film happened in real life," said Jon Abrahams (Steven in Kids). "We fucked up a guy or two or three," he said, referring to the scene where a bunch of skaters beat up a man in Washington Square park with their boards.

But then there are the parts of the story that the cast says were not told accurately, or at all. "We were stealing forties, but we were also stealing food because we were hungry," said Highlyann Krasnow. "We were a family and we took care of each other." Krasnow wasn't in the film, but in real life, her house was the skate crew's crashpad. She was one of those real kids on the edges, just outside the frame. There's some anger about that dynamic still lingering. Hamilton Harris, the skater whose feature scene in Kids taught me (and thousands of other adolescents) how to roll a blunt, recently told Vice that the real people who made up the skate culture the movie was based off got screwed. "People who weren't in it—but who were a part of the group—had gripes with this intrusion into our lives and people making money off it, while we're still struggling, starving, and finding our way through life, alone."

Harris seems to have made amends with Clark, though. Clark has, since day one, given his full support for Harris's new documentary project called The Kids. It evolved concurrently with Caroline Rothstein's 2013 article "Legends Never Die," a retrospective tracking the lives of the skate crew and their extended family after the film, but also the ghosts that seem to have stalked them for the past 20 years.

Take Justin Pierce, considered the rising star of the film when it came out, and who won an Independent Spirit Award for his portrayal of Caspar. He had a few small roles afterward, and in 2000 co-starred in Next Friday alongside Ice Cube. Just a few months after it came out in 2000, though, he took his life in a room in the Bellagio Hotel in Las Vegas. Then there was Harold Hunter, a skater who essentially played himself in the film. Everybody points to Hunter as the engine and the glue; he was the one, they say, who brought together the skaters, the club kids, the suburban refugees and the project kids. When you first got to the city, Hunter was the man to see if you wanted to know what was what. "It's a shame for anyone who didn't know Harold," said Fitzpatrick. "He was the best guy in New York." Hunter died in 2006, after suffering a heart attack in the same East Village housing project he grew up in. He was 31; the cardiac event is believed to have been brought about by a cocaine overdose. (The Harold Hunter Foundation, which works to help foster creativity in and teach life skills to inner city kids, was founded in his name after his death.)

In Janet Maslin's review of the film for The New York Times in 1995, she writes, "Clark makes it sickeningly clear that nobody in Kids has much to look forward to. These kids' future is empty, and their future is now." That sad prophecy became a tragic reality for some of the teens who acted in the movie, and for many more kids on whose lives those characters were based. But it was also why the film resonated so strongly, and why it remains a cultural touchstone: Clark recognized the importance of capturing the impermanence, and vitality, that characterizes the present—both of 1994 New York City, and of a person's teenage years.

"We didn't see the importance of what we were doing," Fitzpatrick said, when asked why the film had such a cultural impact. "We were told by adults that we were fucking up. Larry was the first to say that what we were doing was significant. When you're a teen, everyone is saying you're fucking up...at the time, you don't realize how important that time is."

Correction: This article previously incorrectly stated that Larry Clark is executive producing The Kids. While he fully supports the project, he is not a producver of the documentary film.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Elijah Wolfson is a Senior Editor at Newsweek, where he writes and edits on science, health, technology and culture. He is ... Read more