He goes out to walk the dog, or he asks for another Scotch, or—if he is Richard Holbrooke described by his wife, Kati Marton—he is on the phone planning Christmas and saying, "It feels so good to laugh." Then life changes for her in a moment. Instead of shopping in Paris for aubergine velvet, late-night love calls from Afghanistan, and happiness so intense that superstitious fear tells you it is too good to last, you are catapulted into a world of hospital emergency rooms, doctors with grim faces, and closets filled with suits that suddenly have no one to wear them.

Marton is the latest of the unmerry widows, women who—since Joan Didion wrote about her husband's death in 2005—have described what it's like to suddenly lose a man you have loved for a long time. Holbrooke, Marton's husband of 15 years, died on Dec. 13, 2010, after doctors at George Washington University Hospital spent two days trying to repair his ruptured aorta. Like the others—-Didion, Joyce Carol Oates, and Abigail Thomas, to name a few—-Marton defies the conventional wisdom that good writing is Wordsworthian emotion recollected in tranquility; she seems to be writing the story as it is happening. The book, short and intimate, reads like the wind from the urgency of the opening scene—she is caught in traffic and late to meet Holbrooke, the U.S. special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, for a citron pressé at the Café Flore in Paris.

Later, he sleeps in after a glorious night together in their perfect Paris apartment ("he appears a few hours later, looking sheepish and like an unkempt boy"). They shop for a suit for the upcoming party for her prize-winning memoir about her Hungarian journalist parents—Enemies of the People—and he heads back to Afghanistan.

Even then, life isn't quite perfect. In a bookstore after saying goodbye to Holbrooke, Marton picks up Bob Woodward's Obama's Wars, flips to her husband's name in the index, and finds an infuriating story. She writes, "The President soured on Richard when my husband asked him to call him Richard, not Dick, at the ceremony appointing him special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan." Holbrooke had explained to the president that Kati, who was in the audience, did not like the nickname Dick. Standing in a Paris bookshop, Marton is furious—how can Obama, who doesn't like to be called by his nickname, Barry, be irritated that she doesn't want people to call her husband Dick?

The rich are different from you and me—they are a lot more fun to read about. Marton and Holbrooke's first date was a three-day jaunt to Chartres and the Chateaux of the Loire Valley at Christmastime in 1993. He was in his 50s, the American ambassador to Germany taking a few days off; she in her 40s was just barely separated from anchorman Peter Jennings, one of the most famous men in the world. They talked about Gothic vs. Romanesque, spoke perfect French, and ate at Chez Benoit where they ran into Holbrooke's friend Pamela Harriman, the ambassador to France. (Harriman snubbed Marton.) No sweaty groping in cheesy hotel rooms for these two! Holbrooke's most excited moment was when he and Marton sat side by side in a pew of the great Chartres cathedral. "Just imagine," he whispered urgently, "the pilgrims' first reaction to these windows! The power of this place for medieval peasants." At the end of five days together, they held hands.

And that's not the only difference. Most of us, when packing to move, don't have Bill Clinton drop by to help with the -boxes. (Clinton, opting out of the Richard/Dick controversy, diplomatically always called his friend "Holbrooke.") Most patients don't have Hillary Clinton sitting hopefully beside their hospital bed, or get loving advice from Pakistan's President Asif Ali Zardari about grief; he told Marton that he has kept his wife Benazir Bhutto's room just as she left it. Most of us won't have the president at our husband's memorial services, putting an arm around our shoulders, and most won't see a tall blonde woman hunched inside a black coat, mourning: Holbrooke's former lover Diane Sawyer.

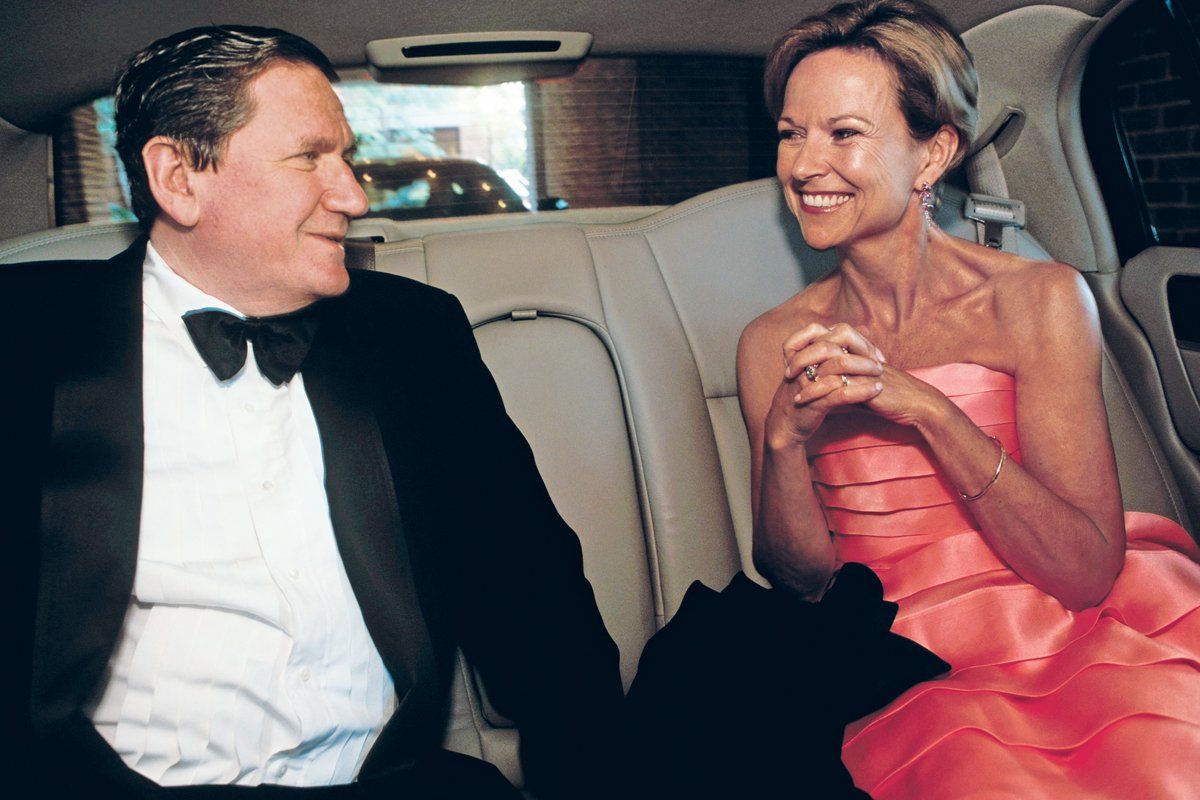

The public face of Marton and Holbrooke's marriage, especially when he was ambassador to the United Nations and their glam dinners included everyone from Whoopi Goldberg to Nelson Mandela, is charming, but Marton is most eloquent in writing about the dishy private parts of their marriage. She describes how her earlier marriage to Jennings—whom she met when he was her boss at ABC News—was derailed by Jennings's brittle insecurity. An old-fashioned man, he was uneasy being with a woman who had her own ambitions and accomplishments. "I wish sometimes that I didn't have these weird bouts of need," he wrote to her in a heartbreaking letter.

He could also be a tyrant. En route to a dinner in honor of Prince Charles and Princess Diana, Jennings appraised Marton's strapless black velvet and asked, "Are you sure you want to wear that?" Seated next to Prince Charles, Marton no doubt delighted him by spending the evening tugging at the top of her dress. But Jennings's emotional withdrawal, and his own rumored infidelities, provoked Marton. Ten years married, with two children, Marton fell in love with someone else—-reportedly Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen, although she does not mention his name in the book—and this was the beginning of the end of the marriage. That affair ended. Then a few months into her separation from Jennings, Holbrooke called.

Holbrooke was a brilliant diplomat who served in the State Department under Presidents Carter, Clinton, and Obama. He had managed the Dayton Accord, which ended the war in Bosnia, and his marriage to Marton was its own kind of détente. When he and Marton fought—about his busyness, about her tendency to exaggerate—he never wavered in his goal: to keep the marriage intact. This eyes-on-the-prize attitude persisted even under the ultimate strain. While researching her own childhood in Budapest, Marton fell for another man, a distinguished Hungarian. "We spoke the language of my childhood and laughed at the same things," she writes. "He knew the words to my favorite childhood song about a lonely fisherman on Lake Balaton." After this affair, 10 years into her marriage to Holbrooke, Marton confessed while sitting on the grass of their house in Bridgehampton. Holbrooke wept, but like a true diplomat he rose above the fray. He never even asked the man's name; when Marton traveled to Budapest, he was unfazed. "I know it took real courage," he wrote Marton about her honesty in breaking off the affair. "If you had not done so our lives would have become increasingly distant and embittered beyond repair. You caused this crisis, but you have also given us another chance." The crisis passed.

What's thrilling about this book is more than cheap schadenfreude. It's about people who do not live the way most of us live—but who have the same problems we have. Bossy husbands, attractive other men, the balancing act of life as a woman, a mother, and a writer, a husband who is working too hard and doesn't get on with his boss: these are the problems all women have in the 21st century even when the boss is not the president of the United States. Great writing is often about yearning, yearning for a lost place, a lost love, or just a lost moment in time. Marton knows a lot about longing for the past. Her own childhood in Budapest ended when her parents were imprisoned long ago. This book feels like her way of keeping Richard Holbrooke alive if only on the page. It works.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.