If you're accused of a felony in the United States, it's likely to take about seven months from the time the case is filed to when it is resolved. But in Sherman, Texas, you'll probably wait a year just to go to trial. And if you're convicted, you might waste away in a county jail cell for a year and a half before you ever receive a sentence.

Sherman is one of the six seats of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, a sprawling geographical region more than four times the size of Massachusetts and covering 47 counties. The Sherman Division alone covers nearly 2 million Texans and sees the majority of the district's criminal cases. But the Sherman Division only has one judge. In March of next year, that judge plans to retire.

The dire situation in Sherman is one example of how federal judicial vacancies at the trial court level are affecting communities around the country, delaying the constitutional right to a day in court. A new study, "The Impact of Judicial Vacancies on Federal Trial Courts," released Monday from the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonprofit law and policy institute based at New York University School of Law, highlights the effects of the approximately 50 empty district court judgeships.

The record level of vacancies is due largely to Republican opposition to President Obama and his judicial nominees. Whereas partisan battles over appellate court appointments is not a new phenomenon, the politicization of judicial appointments has trickled down to the district courts, the workhorses of the federal justice system which handle the majority of federal cases.

"If you look at district court vacancies since 2009 when Obama took office, they really have broken with historical patterns," Alicia Bannon, an expert in judicial selection at the Brennan Center and the author of the study, told Newsweek. "They've been not only high but sustained basically since 2009."

Republican senators have substantial powers to block nominees in their states. Senators can stall in the consultation process with the administration over nominee selection—Bannon says the fact that a substantial number of vacancies without nominees are concentrated in states with GOP senators is an indication that this is indeed happening.

Once the White House selects a nominee and refers it to the Senate Judiciary Committee for confirmation, a committee tradition called the "blue slip" process can tie up a nomination indefinitely. When a nominee is referred to the committee, the two senators from that state are notified on a blue slip of paper. To signify their support for the nominee, they return the slip. Thus far, the committee's chairman, Senator Patrick Leahy, D-Vermont, has held fast to this tradition. Many though not all Republican senators have simply not returned blue slips, essentially a pocket veto of the nominee.

One of the results of this phenomenon has been a concentration of long vacancies in states with Republican senators. Nearly 20 percent of all district court vacancies are in Texas, for example, and most of those seats don't even have nominees awaiting confirmation yet. "That's the terrible irony of it, is that they are hurting their own districts," Bannon said.

The Eastern District of Texas has two vacancies, including one in Sherman. The first current vacancy came in October 2011, the second in March 2012.

After more than two years with two vacancies, on June 26, 2014, the White House named two nominees to fill those seats. It is unclear whether Texas Republican Senators John Cornyn and Ted Cruz have received or returned the blue slips. Next year, two more judges in the same district, including the sole judge in Sherman, plan to retire.

In the new Brennan Center report, Bannon selected 10 court districts around the country and interviewed judges, court clerks and lawyers practicing in those districts to assess the human impact of the vacancies. At the time of her interviews, all had at least one vacancy and all but two had at least a 15 percent vacancy rate compared to the total number of judges. The districts in the study are the District of Arizona, Eastern District of California, Northern District of California, Middle District of Florida, Southern District of Florida, Eastern District of Michigan, District of Nevada, Western District of New York, Eastern District of Texas and Western District of Wisconsin.

"The key finding of our report is that vacancies are hurting our courts and the individuals that rely on them to resolve their disputes and defend their rights," Bannon said.

The most common observation from judges in these districts was that there were delays throughout the entire process taking a case to court.

In Sherman, to take one of the most dramatic examples, the long waits for trials and then sentencing have serious effects. One lawyer described a situation in which, as the report detailed, "he has a client sitting in jail awaiting trial who will see co-defendants who pleaded guilty finish their prison terms before her case is even heard." This means that people accused of a crime are told that if they plead guilty, they will be out of prison in less than the time it takes to have their day in court. "It undermines your ability to truly go to trial and defend yourself because you think you're innocent," explained the lawyer, who is quoted in the report. "The delay is so much, it's easier to take the plea."

"When I started doing this work 15 years ago, or even six or seven years ago, our big fear was that a judge would tell you to be ready for trial in 90 days," the lawyer continued, pointing to the vacant seat as well as a growing number of criminal cases for the long delays today.

For anyone who needs to go to court to assert their rights, the vacancies are problematic, and not just in Sherman. "We don't neglect the Seventh Amendment, the right to a civil trial," Chief Judge Skretny of the Western District of New York says in the report. "But we tell people, if this is what you want to do, it will take time to get there."

Vacancies also threaten a judge's ability to do his or her best work. It's simple math: As caseloads go up, judges don't have as much time to spend on each case. The problem persists at the appellate level, where vacancies mean that circuit court judges are less likely to catch any errors made by the lower courts.

"It affects the quality of justice that's being dispensed," Leonard Davis, the chief judge of the Eastern District of Texas, says in the report. Two judges in his district routinely travel to Sherman from other divisions to hear cases, but the 350-mile trip means they waste days traveling when they could be working.

It's a problem the report found in many districts with vacancies and heavy workloads. "I tend to think it results in less time to actually reflect on what's being submitted," said a lawyer in Eastern District of California, a district which has not only struggled with vacancies but has the third highest caseload per judge in the country. "They might call it 'efficiency,' but one might also call it 'rushed rulings.'"

The passage of time can also prejudice the outcome. "People lose their memory of what occurred, evidence spoils, people die. It's not a good thing," the chief judge in the Eastern District of California, Morrison England, says in the report.

The vacancies exacerbate what is already a nationwide issue: the need for more judgeships. Congress has not created any new district court judgeships since 2002. Based on workload, the Judicial Conference of the United States recommends additional judgeships in more than a third of the 94 districts. Adding the vacancies to the need for additional judgeships leaves 20 districts with an effective vacancy rate of 25 percent of higher.

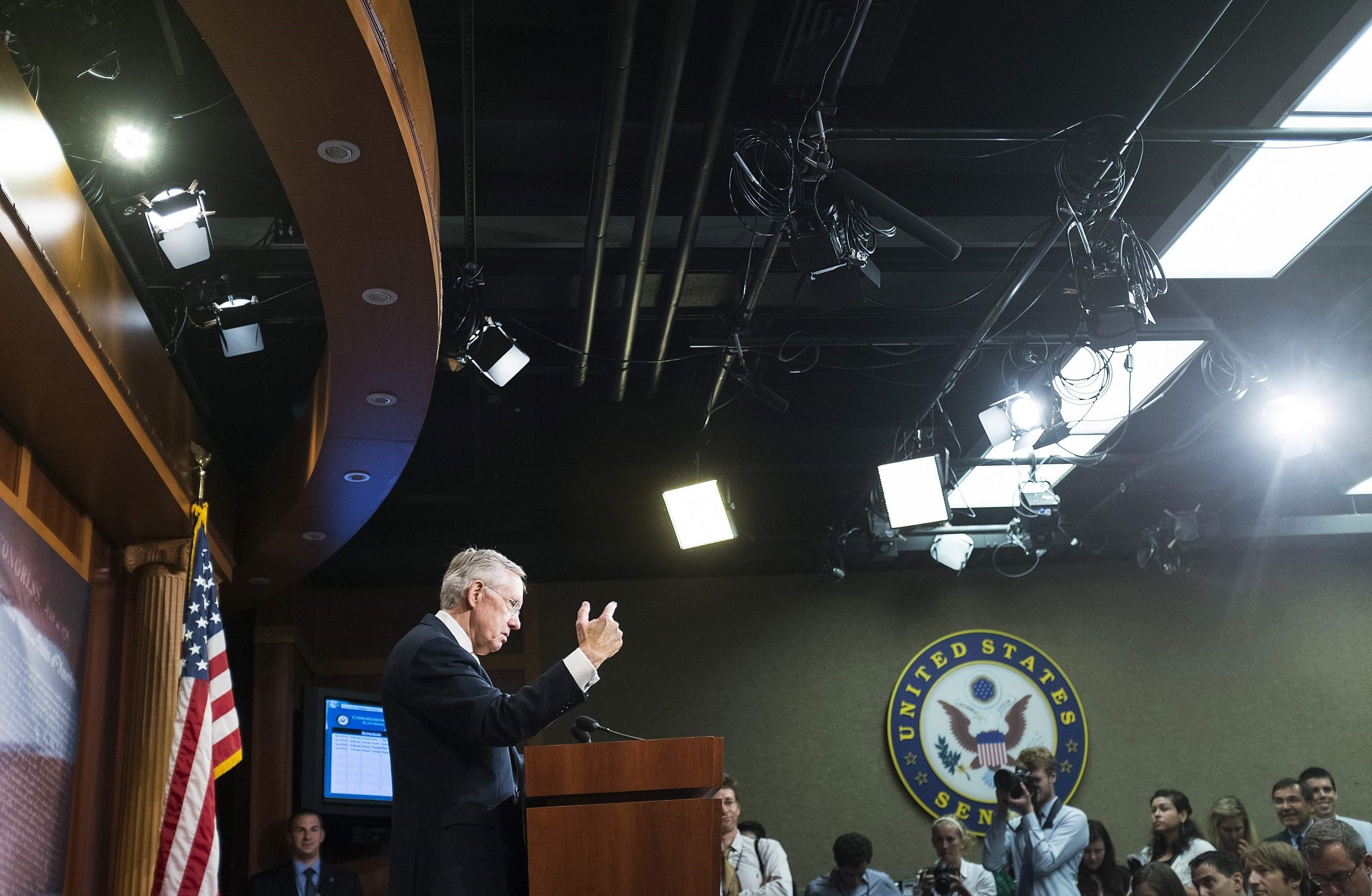

Congress has made no indication that it will increase the number of district court judges, but the Senate has addressed the vacancy crisis with a flurry of confirmations since April 2014. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nevada, has put a premium on confirming judges and eliminating the filibuster for judicial nominations last November means Republicans can no longer block nominees once they come up for a vote.

But they can delay those nominees, and they still do. Republicans routinely drag out the confirmation vote process by forcing the Senate to take up the required debate time per nominee, even when there is no substantial debate needed. The ultimate result will be fewer nominees confirmed. Though Bannon is happy to see Reid pushing confirmations through, she fears it won't solve the problem.

Of the 50 current vacancies on the trial court level, only half even have nominees named. Nine more vacancies are expected to open up before the end of the year. And the rapid pace of confirmations is likely to slow. Bannon notes that the focus on judicial confirmations has come at the cost of executive confirmations. At some point soon, she expects Reid to pivot to those pending nominations. And then there's the upcoming midterm elections, which political forecasters say is likely to put Republicans in control of the upper chamber.

Bannon hopes that a Republican majority would continue to confirm judges, but it's unlikely the White House and a GOP-run judiciary committee would agree on many nominees.

"My hope is that senators will prioritize filling these seats because there is desperate need, oftentimes in their own states," Bannon said. "That said, I think it's certainly a concern that [filling] these vacancies could slow down again. We've seen years of slow-walking judicial nominees."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Pema Levy is a Washington Correspondent for Newsweek, covering Congress, elections and dabbling in court battles and other political miscellany. ... Read more