It was lateon a summer's night in 2009 when John McCain met Muammar Gaddafi, whose behavior bordered on the bizarre.

The Libyan leader, a map of Africa emblazoned on his shirt, was ensconced in a tent in Tripoli with horses exercising outside when he turned to the visiting senator and said, "If you had withdrawn all the troops from Iraq, you would have been elected president." McCain, concluding his host was crazy, countered: "I can think of a lot of reasons I lost, but that wasn't one I had seriously considered."

Less than two years later, McCain was back in the region, watching TV in Tunisia as the first street protests erupted in Libya in mid-February. As McCain and his Senate wingman, Joe Lieberman, traveled on to Lebanon and then Jordan, they spent hours discussing whether to support U.S. military action against Gaddafi. Once they came out for a no-fly zone, McCain grew increasingly frustrated as, in his view, the administration dithered—a delay he blames on President Obama's "world view, and a belief we don't act unless it's with other countries." Twisting a Sharpie in his Senate office as he speaks in staccato bursts, McCain says, "I don't think he feels strongly about American exceptionalism."

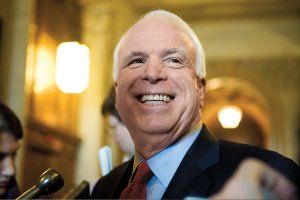

The battle-scarred warrior who lost to Obama two and a half years ago is again finding his voice—jolted into action by the revolutions catching fire across the Middle East. The Arizona Republican, a onetime Navy pilot famously shot down over Vietnam, has a passion for military matters that has always far outstripped his interest in domestic issues. McCain is taking some serious shots: he says Gaddafi would be gone had Obama started the bombing sooner, and that the president should never have relinquished control of the mission to NATO. But he has broken with conservative elements in his own party in backing Obama—going further than many war-wary Democrats.

Some in McCain's orbit believe he occasionally enjoys a bit of schadenfreude at the president's difficulties. But Mark Salter, McCain's longtime confidant, says, "More than anybody, he's responsible for normalizing relations with the North Vietnamese. If he had a grudge against anyone in the world, you'd have thought it was them."

Both sides have felt the friction. During a health-care meeting last year, the president chided McCain, "We're not campaigning anymore. The election is over." But Obama had him in for an Oval Office chat after the senator praised his speech on the Tucson shootings, and that has defrosted the relationship. McCain "does not play a tremendous amount of politics" on foreign issues, says Obama communications chief Dan Pfeiffer. The two "have a similar orientation of looking for common ground, even if it means angering members of your own party." McCain became a media darling for doing just that—until he ran against Barack Obama. "When I go after a president of my own party," he says, the press calls him "a maverick. When I was going against a president of the other party, arrhh."

McCain's renewed sense of engagement is a sharp contrast to the disappointment of 2008. Some friends say he slid into grumpy-old-man mode; others go further. "He was white-hot angry," says an associate who requested anonymity to candidly describe encounters with McCain. "At everybody—himself, the media, the staff, the world."

He now sounds philosophical; after all, he has been through this before. After his 2000 presidential campaign, McCain says, "I spent some time feeling sorry for myself and it didn't do any good." Now the 74-year-old lawmaker tries to avoid thinking about how a McCain White House would have handled global conflicts: "There's no point in it. I was defeated fair and square. It's just not appropriate. It's not appropriate for me mentally. The cure to defeat is get busy, get busy, jump right back in."

McCain, who insists on visiting Iraq and Afghanistan twice a year, often favors a muscular approach to projecting U.S. military power but is wary of entanglements with no exit strategy. The old aviator, who had both arms repeatedly broken in a Hanoi prison camp, says that experience has "also given me a sense of caution in light of our failure in Vietnam." While McCain opposed the U.S. military actions in Lebanon and Somalia, he is sympathetic to humanitarian missions—and would even consider sending troops to the war-torn Ivory Coast if someone could "tell me how we stop what's going on."

Pressed on when the United States should intervene in other countries, McCain sketches an expansive doctrine that turns on practicality: American forces must be able to "beneficially affect the situation" and avoid "an outcome which would be offensive to our fundamental -principles—whether it's 1,000 people slaughtered or 8,000…If there's a massacre or ethnic cleansing and we are able to prevent it, I think the United States should act."

That philosophy, applied to Gaddafi, has drawn fire from J. D. Hayworth, the conservative ex-congressman who mounted a failed primary challenge to McCain last year.

"I thought his conversion to conservatism might last a little longer," says Hayworth, who believes McCain has embraced Libya's rebels without knowing much about them. "With reelection safely behind him, he will take what he calculates to be the most attention-getting posture."

Some liberal critics, meanwhile, have faulted McCain for supporting Bush-era warming of relations with Gaddafi, only to denounce him now as a man "with blood on his hands."

McCain defends the 2009 meeting with Gaddafi, who was reducing his nuclear stockpile. Much has changed since then, McCain says, and besides, he has met with plenty of despots.

McCain admits, "I haven't always done what I thought was right," and can betray a hint of self--righteousness toward politicians who compromise. While he backed Obama for sending 30,000 more soldiers to Afghanistan, McCain was appalled by the announcement that troop withdrawals would begin this July. "I believe the president was influenced by political considerations," he says as if he were spitting out an epithet, "to give some kind of comfort to the left wing."

An hour before a Senate hearing, McCain sees a report on his iPhone that Misrata has become a center of human suffering in Libya, leaving him in a foul mood. He presses Defense Secretary Robert Gates and Joint Chiefs chairman Mike Mullen on why they pulled their A-10 and AC-130 warplanes as the rebels retreated. "Your timing is exquisite," McCain says, voice tinged with sarcasm. Last week he was huddling with John Kerry on a symbolic Senate resolution blessing the military action in Libya, while admitting the wording would be "vanilla."

On a recent afternoon, after a signal from his staff, McCain bolts out of his office, makes his way to the Capitol subway, and strides onto the floor. "Had we not taken action in Libya, Benghazi would now be remembered in the same breath as Srebrenica—a scene of mass slaughter and a source of international shame," he thunders. But the blue-carpeted chamber is empty, the oration delivered for the C-Span cameras.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.