Last year, in the same month he turned 50, Jeff Tweedy lost his father to lung cancer.

Loss has a way of shifting one's mind to the past. The Wilco frontman was already buried in reminiscence. He was in the middle of writing a memoir, recounting his life story: his punk awakening in a depressed Illinois town known as the Stove Capital of the World, his formative years slumming it in the influential alt-country group Uncle Tupelo, his struggles with anxiety and drug addiction, and, of course, his war stories as the leader of Wilco, the Chicago band that has come to be uniquely beloved by fans of raggedy, progressive-minded indie-rock.

And then his father, a railroad employee of nearly five decades, died, with son and daughter and grandchildren singing "I Shall Be Released" by his bedside. When Tweedy recalls that day, his voice grows faint. "My dad's girlfriend, Melba, was holding his hand and telling him to go ahead because Jo Ann—that's my mom—is waiting for him. I don't believe in that. But I'm sitting there, holding his hand. It's hard not to be impressed by the poignancy of that deep wish."

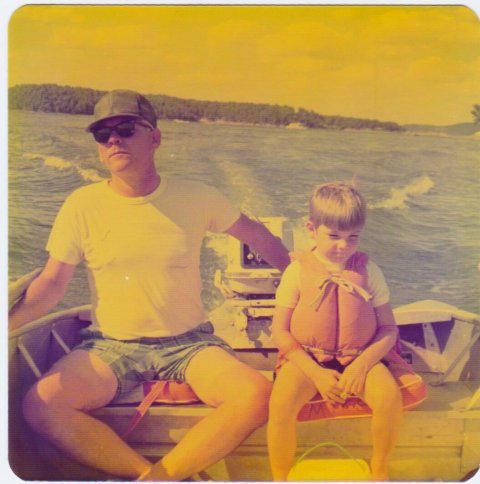

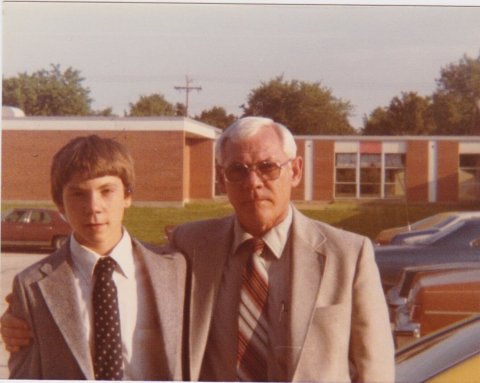

Tweedy looks different these days: He's got a neck beard and silvery hair flowing from a black ski hat, emblazoned with "GIVEASHIT" on it. A drab conference room is a strange place to be talking to a rock star about the afterlife, but here we are. We've met at the New York offices of Penguin Books, which is publishing his book (through the Dutton imprint) on November 13. It's a funny and candid addition to the rock-memoir genre, and it takes its title, Let's Go (So We Can Get Back), from a catchphrase Tweedy attributes to his father. "He was a very selfish man," the songwriter admits. But the two grew closer in his final years—more than it had once seemed possible. "It tends to turn your mind towards reflection when you're confronted with your parents' mortality," Tweedy says. After his death, "I spent a lot of time at the house I grew up in, getting it ready to be sold, going through my old stuff. I'm sure it helped the book."

Tweedy's early life revolved around music: an older brother with an outré record collection, formative experiences at Ramones and Replacements gigs. He taught himself guitar, by chance, in 1980, during a summer spent immobilized by a bike injury. (His life's great blessing-in-disguise, that bike crash.)

In ninth grade English class, he met a fellow Sex Pistols fan named Jay Farrar, who would become his songwriting partner in Uncle Tupelo during the late 1980s. The band played a mix of roots music and punk that came to define alt-country, and when Tweedy's relationship with Farrar soured, he formed Wilco in 1994. (Farrar, in turn, became the frontman of Son Volt.) Wilco's first album, A.M., didn't make much of an impression, but its second, 1996's Being There, was a sprawling double-LP showcase of Wilco's stylistic range, from sugary power-pop to sad-bastard balladry.

Five years of critical acclaim culminated with a now-legendary creative-control standoff with Wilco's record label, Reprise, which refused to release the band's avant-pop masterpiece, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. Label executives deemed it uncommercial and didn't hear a hit. Yet the band refused to budge from its dense, almost kaleidoscopic production. "I was convinced we had made the most accessible pop record we had ever made," Tweedy tells me.

His book chronicles the messy dispute, and the industry's embarrassing shortsightedness: Yankee became the band's biggest-selling album—after Wilco happily got dropped, regained the master tapes for free and shopped them around to other labels. "I appreciate that they were so up front about their distaste," Tweedy says now. For one thing, it meant Yankee was delayed past its planned release date: September 11, 2001. Considering the album has two towers on the cover and a song titled "Ashes of American Flags"—sheer coincidences, Tweedy swears—the songwriter suspects it might have been pulled from stores.

For another, it pushed the band to eventually form its own label. And as Wilco's universe has grown increasingly insular—determining its own release schedules, operating its own studio, The Loft, and even hosting an annual a summer festival—Tweedy has become more prolific. He has released a new record every year since 2014, either with Wilco or on his own (including the father-son project Tweedy). That would be impossible "if we had to deal with the bureaucracy of a bigger label," he says.

For Tweedy, it's a big year for revelation. In addition to the memoir, he will release Warm, his first-ever solo album of new material, on November 30. Like Wilco's recent Schmilco, it's predominantly acoustic, autumnal and intimate in scope. It's also, says Tweedy, his first set of songs written with the intention of telling the listener something about himself. "We started recording basic tracks before my grandpa passed away," says his 22-year-old son, Spencer, who plays drums on some of the songs. "The lyrics were finished afterwards." Which is not to say it's a grief album. "Grief has a connotation of dourness and solemnity to me," Spencer says. "That's not what recording is like for us."

The albumis as plainspoken and personal as Tweedy has ever been in his songwriting, with songs of familial love ("Don't Forget") and reflections on addiction ("Having Been Is No Way to Be"). The novelist George Saunders, who wrote the album's liner notes, put it this way: Warm courses with gratitude, joy "and a sense of wonder at the realization that death, for as much as we fear it, does not actually negate anything, or anything essential."

* * *

Tweedy can be bracingly funny in a self-deprecating way, and his memoir's introduction contains a particularly good joke. He warns his readers that there will be "no mention" of his well-documented addiction to prescription painkillers. "I want to put those years behind me," he writes—and anyway, Vicodin abuse isn't exactly a riveting story. Pause. Record scratch. "Jesus, of course I'm going to write about the drugs," he concedes. "I'm pulling your leg."

In fact, the story of Tweedy's debilitating addiction was central to why he chose to write a memoir: a hope that his recovery story might help others struggling. "Just being a person that's still alive is hopefully helpful," he tells me with a morbid laugh. Which is not to say that recovery is the only story Tweedy is here to tell. For those more interested in anecdotes about dysfunction within Uncle Tupelo or details on how Wilco recorded the noise passage at the end of "Poor Places," there's plenty of that, too. Addiction was just the story he felt he had to tell, in the hope it might help someone else. "The fact that I've gone through rehab," he says, "and had some pretty public struggles with depression and opioids—I feel like that's a good reason to share your story."

Tweedy's addiction wasn't the archetypal rock star hedonism. He quit drinking in his early 20s, heeding a family history of alcoholism, and was never attracted to Oasis-style debauchery. His Vicodin addiction was a means of coping with panic attacks and severe migraines, which have plagued him since he was a child. "He would get these debilitating headaches, and he would deal with it with Vicodin or Oxycontin," says Wilco drummer Glenn Kotche, who joined the band in 2001. "I just thought these were being prescribed to him." (Which for a while they were: Tweedy had convinced a psychiatrist to prescribe him Vicodin for anxiety.)

Tweedy began taking Vicodin in the late 1990s, and eventually only felt normal when using painkillers. In 2003, while recording Wilco's fifth studio LP, A Ghost Is Born, Tweedy sank into a terrifying cycle of panic attacks and pill binges. He became convinced he was going to die. "A Ghost Is Born would be a gift to my kids, who could turn to it when they were older and put together the pieces of me," he writes. It's one explanation for why that album radiates so much dread—including a 12-minute noise drone intended to mimic the experience of Tweedy's migraines. (The follow-up album, Sky Blue Sky, sounded so serene in comparison, an infamous Pitchfork review helped popularize the term "dad-rock." Tweedy describes it, in retrospect, as his recovery album.)

One surprising revelation from Tweedy's addiction years involves the firing of multi-instrumentalist Jay Bennett, a key component of Wilco's most ambitious albums. Around the time of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, Tweedy found himself playing CEO of a revolving-door lineup. The conventional wisdom is that he axed Bennett in 2001 because of creative disputes while making Yankee, a theory supported by the Wilco rockumentary I Am Trying to Break Your Heart. But in his book, Tweedy says the decision had more to do with Bennett's own pill addiction and unwillingness to seek help. "It was about self-preservation," he writes. "I fired Bennett from Wilco because I knew if I didn't, I would probably die." (Bennett did die, of a fentanyl overdose, in 2009.)

At his lowest point, Tweedy stole morphine from his mother-in-law while she was dying from cancer. "Oh, it's shameful," he says now. "The only room for forgiveness I can give myself is that there's a sociopathy that comes with being an addict. I wouldn't say, 'That wasn't me, that was the disease.' But the only way to take responsibility was to stay committed to being healthy."

Which he is, nearly 15 years after a stint in a dual-diagnosis rehabilitation facility. That wasn't easy, either. "When I went into the hospital for rehab, that was like, Oh my god, now I know where hell came from," he says. "I was in a place in my life where I really felt eternally damned."

At 51, Tweedy seems mostly grateful: Grateful to have survived that nightmarish battle. Grateful for devoted Wilco fans, who flood western Massachusetts each summer for the band's Solid Sound festival. And grateful particularly to his wife, Susie, for whom his love, he writes, is "too big for songs." He still deals with panic issues sometimes, but certain things help: "[Being] properly medicated. Talking to the right people, when I need to talk. And just collecting evidence over a longer period of time that I'm not going to die when I'm having a panic attack. You start to amass this catalogue of instances where you thought you were going to die and you didn't."

* * *

Certain songwriters can be precious or secretive about their writing process, but Tweedy's book lays it bare: how he writes melodies first, lyrics second; how he records "mumble tracks" over his demos—gibberish guide vocals before the actual lyrics have formed; how he nicked imagery from Henry Miller while writing Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. In the book, he also identifies his greatest virtue as a songwriter: "My comfort level with being vulnerable is probably my superpower." (Tweedy's Twitter bio cheekily identifies him as an "insecurity expert.") His bandmates agree. "He can be disarmingly honest onstage," Kotche says.

At some point during the last decade, Wilco developed a reputation for amusingly half-assed album titles. It's a running joke among fans, though understandable, I suppose, when you release one album titled Wilco (the Album), another called Schmilco and another titled, bewilderingly, Star Wars. (Tweedy thought George Lucas would try to block it, but he didn't.)

Warm might seem like a puzzling title for a solo record. But it would be a mistake to place it in the what-a-lazy-title category. It originates with the album's most affecting song, "Warm (When the Sun Has Died)," which centers around Tweedy's reflections on the afterlife. "Oh, I don't believe in heaven / I keep some heat inside," Tweedy sings over a mournful pedal steel refrain. "Like a red brick in the summer / Warm when the sun has died."

That warmth is a mysterious, benevolent thing. Not religion, exactly, says Tweedy, because he's not religious. (His wife is Jewish, and the book mentions a conversion ceremony—involving, yes, a circumcision—around the time of his younger son's bar mitzvah.) But he does find a sense of belief difficult to shake. Like that hopeful vision of his late father, reuniting with his mom. "As much as I don't believe in God, I don't believe in atheists either," says Tweedy. "I know that inside, the part of me I can't be dishonest about, is the side that would like very much to believe in something." For it not to exist, "I would have to actively try to kill that childlike side of myself.

"I might sound cool and tough if I told you I just don't believe in God—you die and, whatever, it's done," he adds. "Probably true. But that doesn't stop me from having that thing. Whatever that thing is."

About the writer

Zach Schonfeld is a senior writer for Newsweek, where he covers culture for the print magazine. Previously, he was an ... Read more