Ancient humans hunted and butchered a cave lion around 48,000 years ago, a study of the prehistoric big cat skeleton has found.

The study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, describes what researchers say is the first direct evidence of cave lion hunting among Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis)—one of our closest extinct relatives with whom we share a common ancestor.

The findings represent the "earliest direct evidence of a large predator being hunted and killed in human history," study author Gabriele Russo, a Ph.D. candidate in zooarchaeology at the University of Tübingen's Institute for Archaeological Sciences in Germany, told Newsweek.

The paper also provides the earliest evidence of Neanderthals exploiting a cave lion pelt around 190,000 years ago, according to the researchers.

The findings of the study shed new light on the interactions between these ancient hominins (the group consisting of all modern and extinct humans) and Eurasian cave lions (Panthera spelaea), an extinct big cat species that resembled modern lions.

Neanderthals emerged in the Middle Pleistocene period, which ran from roughly 780,000 to 126,000 years ago. The earliest known Neanderthal-like fossils date to around 430,000 years ago.

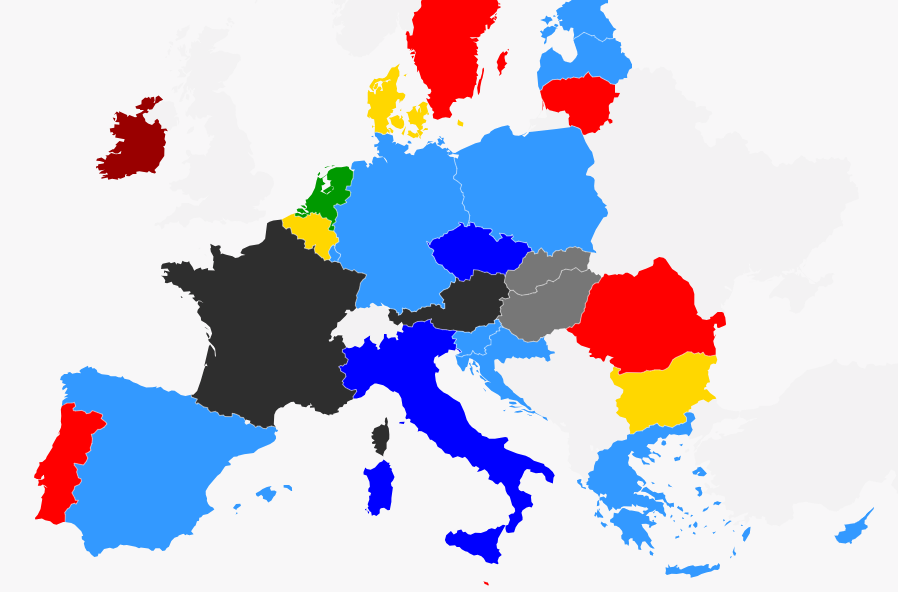

These hominins lived in Eurasia, briefly co-existing and sometimes interacting with our own species, Homo sapiens, before disappearing around 40,000 years ago.

In the study, Russo and colleagues analyzed the almost complete 48,000-year-old remains of a cave lion that is thought to have been about the size of a large modern African lion male and relatively old when it died. This skeleton was originally excavated in 1985 in the municipality of Siegsdorf, in southeastern Germany.

Previous examinations of the cave lion specimen had identified cut marks across several of the bones, including two ribs, some vertebrae and the left femur, suggesting that ancient humans had butchered the big cat after it died.

The study has revealed new details regarding the lion's demise, describing a partial puncture wound on the inside of the lion's third rib, which appears to have been made by a wooden-tipped spear. The puncture is angled, suggesting the spear entered the lion's body through the left side of its abdomen and pierced vital organs before coming into contact with the third rib on the right side.

The nature of the puncture wound bears similarities to others previously found on deer vertebrae that are known to have been made by Neanderthals.

As a result, the authors of the study proposed that Neanderthals killed the cave lion—which was likely in poor condition—with a wooden spear and processed the carcass at the kill site in order to exploit its meat before abandoning it. Thus, the specimen from Siegsdorf provides the earliest evidence of these Neanderthals purposefully hunting cave lions, according to the study.

"Based on our knowledge, they approached the butchering process with care. They began by eviscerating the animal and removing its internal organs without causing damage to the ribs," Russo said. "Additionally, they extracted the meat from the muscles without disarticulating or breaking any bones for marrow extraction."

The relationship between early humans and lions is poorly known, despite these animals being a prominent feature of cave art made by prehistoric Homo sapiens.

"These interactions are exceedingly rare. We may be aware of only about 20 sites across Europe that extend back over 350,000 years with evidence of human-cave lion interactions, including those involving Homo sapiens. However, the scarcity of these findings is not unexpected," Russo said.

"Fossils, in general, are extremely uncommon—fossils of large cats are even more so. As in the case of the lion from Siegsdorf, stumbling upon them often comes down to sheer luck. Furthermore, even after their discovery, they sometimes end up being overlooked or forgotten," he said. "Previously, our knowledge [of Neanderthal-cave lion interactions] was limited to a scant few instances scattered across time and space, primarily comprising isolated bones of lions bearing cut marks, implying some form of processing."

The oldest of these instances, dating back to approximately 350,000 years ago, was discovered in Grand Dolina, Atapuerca, northern Spain, and was detailed in a study published in 2010.

"In this case, the evidence includes both cut marks and impact marks, indicating that a lion was definitely butchered and maybe killed, as suggested by the authors. However, there is no direct evidence to support the latter," Russo told Newsweek.

In the latest study, the researchers also analyzed a set of cave lion paw bones that Russo and colleagues uncovered during excavations at the "Unicorn Cave" in the borough of Herzberg am Harz, in central Germany. These remains date to around 190,000 years ago.

An examination of the bones revealed cut marks consistent with those produced when an animal is skinned. The evidence suggests that the bones were left within the pelt of the lion, which was then abandoned at the site.

These findings may represent the earliest evidence of Neanderthals exploiting a lion pelt, potentially for cultural purposes, according to the study.

The nature of the cut marks indicates that the ancient humans responsible for skinning the animal were careful in their approach, ensuring that the claws remained preserved within the fur. The findings of the study have implications for our understanding of the relationship between ancient humans and these animals.

"The notion that Neanderthals interacted with cave lions holds deep significance," Russo said. "It reveals that Neanderthals were actively engaged with their environment, which included encounters with formidable creatures like lions."

"These interactions encompassed not only the cultural use of lion body parts but also the ability to hunt them. Initially, this behavior was exclusively attributed to our species, Homo sapiens. However, Neanderthals were the first in the hominin lineage to gain the upper hand over predators, pioneering cultural relationships with them," he said.

Nuria García García, a paleontologist with the Complutense University of Madrid, Spain, who was not involved in the latest research, told Newsweek that she agreed with the paper's findings.

"The authors review the evidence on cave lion hunting, and I agree this is the first evidence of this practice by humans. The study is very convincing with the marks observed in bones. They really seem to be produced by human tools instead of by carnivores," she said.

Update 10/18/23, 2:22 p.m. ET: This article was updated with comment from Nuria García García.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more