You're familiar with the stereotype: humorless, ever so slightly imperious, Birkenstock-wearing brown-rice enthusiasts. These are the women of NPR, forever etched into America's collective consciousness by Alec Baldwin, Ana Gasteyer, and Molly Shannon in a classic Saturday Night Live skit known as "Schweddy Balls." Despite its reputation for earnestness, the organization seems to be in on the joke. Even Nina Totenberg, the longtime justice reporter whose legendarily soothing voice almost surely provided inspiration, laughs about it. "I like that Saturday Night Live makes fun of us," she says. "It's better to be noticed than not noticed at all."

Today Totenberg is the dean of the Supreme Court press corps; NPR progamming reaches an audience of nearly 23 million—a 70 percent increase from 1998, the year the skit first aired—and has more foreign bureaus than any other American broadcast network. But it hasn't always been that way, and Totenberg knows what it means to go unnoticed. She joined the fledgling broadcaster in the early 1970s, when it was carried by just 90 stations (that number has since increased to more than 900). It was a period in which most news outlets were openly hostile to the very notion of hiring a female correspondent. "All of us have stories of being told, outright, 'We don't hire women' or 'We have our woman,'" she says.

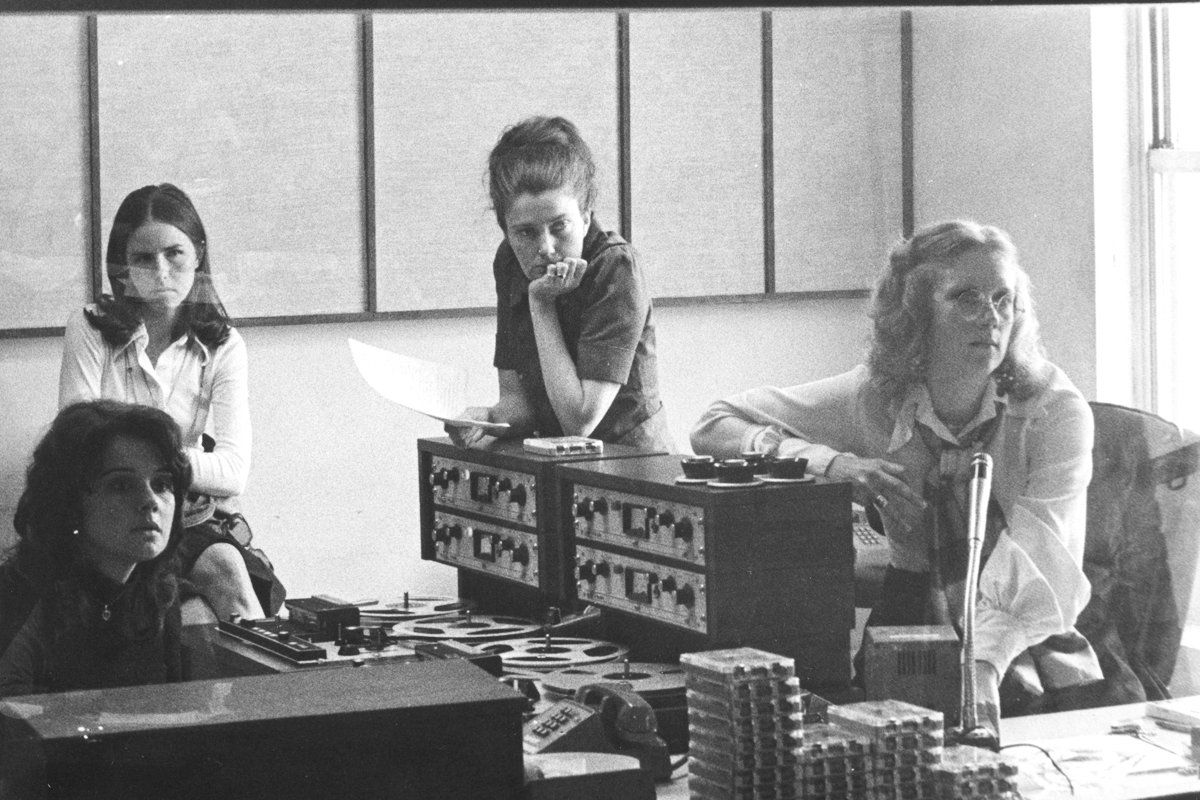

In part, Totenberg says, NPR had no choice: salaries were so low that few men were willing to take jobs there. The inadvertent result was a roster of young female talent now considered among the most respected names in radio: Totenberg, Cokie Roberts, Linda Wertheimer, and Susan Stamberg, a group affectionately known as the "Founding Mothers." "It was a novel experience, being looked after [by colleagues] and not being hit on," Totenberg says. The Old Girls' Club, as she calls them, sat in a corner of the newsroom the men referred to as "the fallopian jungle," and swiftly became the broadcaster's earliest stars. In 1972, Stamberg became the first woman in the country to anchor a daily national news show.

We've come a long way since the 1970s, but in terms of women's achievement, NPR is still a notable outlier. Two years ago, Audie Cornish left her post at NPR's Southern desk to cover Capitol Hill. "My very first day, I walked into a press conference and it was all young reporters," she says. "Every single one of them was white and every single one of them was a man. I was like, whoa, this is not how we roll at NPR." In February, the Women's Media Center's annual report found that women make up just 18 percent of radio news directors and 22 percent of the local radio workforce overall. A recent examination of some of the world's most prestigious literary magazines was similarly dispiriting: with only a few exceptions, male bylines outnumbered women's by three to one. At NPR, meanwhile, women hold the top editorial position at five of the seven news programs, and make up nearly half the overall staff.

According to staffers, it's the Founding Mothers themselves who are responsible. "Mentoring" can sometimes seem like a meaningless buzzword, particularly in a competitive news environment. But at NPR it's serious. "This is how you get ahead in the media world—by helping each other out," says Cornish, who is now, at 32, the network's youngest anchor. "I would not be here if all those people did not take an interest in my career. That's just the fact of it."

Dozens of studies have proved the benefits of diversity: varied experience and opinion counter "group think" and strengthen ideas. Case in point: NPR's Morning Edition has some 12 million listeners, more than twice the viewership of the Today show. And the women running overseas bureaus have brought home a host of Peabody Awards, including one for Sylvia Poggioli's coverage of rape as a weapon of war in the Balkans, and for Kabul bureau chief Soraya Sarhaddi Nelson's series on opium-addicted Afghan mothers. "They are able to get at stories that other people wouldn't have had an interest in," says Morning Edition executive producer Madhulika Sikka. "And wouldn't have been able to penetrate anyway."

Of course, stories needn't always be serious. I sat in on an editorial meeting—one attended by 16 people: three of them white, two of them male, none of them both—where Tell Me More host Michel Martin mentioned a new study about fashion trends causing physical injury. Everyone laughed at the dangers of skinny jeans, but the discussion that followed was the most animated part of the meeting.

Afterward, Martin, a former producer at ABC, admitted that the item would have been more difficult to raise were she, as she was at Nightline, the only female producer in the room. Here, she says, "you can be comfortable with your judgments and not second-guess your instincts as a journalist. It's almost like you're not always looking at yourself to see how you're being viewed."

That said, no workplace is perfect, and NPR isn't immune to controversy. "Every group in power seeks to normalize itself, and people here have the same blind spots any other group has," says Martin. "Yes, you can have open conversations about breast-feeding, but that does not mean that there are not insensitivities to other realities. Two words: Juan Williams."

The Williams debacle—the news analyst's 2010 firing was so badly bungled that then-CEO Vivian Schiller and VP for news Ellen Weiss were forced to resign in its wake—continues to cast a long shadow. One senior staffer referred to the affair as "The Troubles." Everyone is understandably eager to move on. "It's not a perfect place; it has its flaws," Totenberg admits. "But I've worked in a lot of other places, and compared to them, it's like a very pure diamond."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.