Among American spies there's more than a little nostalgia for the bad old days. You know, back before dictators started toppling in the Middle East; back when suspected bad guys could be snatched off a street somewhere and delivered to the not-so-tender mercies of interrogators in their home countries; back when thuggish tyrants, however ugly, were at least predictable.

It's not a philosophical thing, just a practical one. Confronted by the cold realities of this year's Arab Spring, many intelligence and counterterrorism professionals now see major dangers looming near at hand, while the good news—a freer, fairer, more equitable and stable Arab world—remains somewhere over the horizon. "All this celebration of democracy is just bullshit," says one senior intelligence officer who's spent decades fighting terrorism and finds his job getting harder, not easier, because of recent developments. "You take the lid off and you don't know what's going to happen. I think disaster is lurking."

To be sure, Osama bin Laden has finally been terminated, but the impact of that single operation on Al Qaeda and its affiliates may have been both overrated and overstated by a U.S. administration anxious to score political points. If, as claimed, bin Laden was still directing operations, what were they? No actual plots have been publicly identified. "Bin Laden needed killing, and I am glad he is dead," says another veteran American operative—let's call him Mr. Mum, because he's not authorized to speak on the record. "But bin Laden is what he was: this old guy who got lucky on 9/11, sitting in a crappy little room watching a crappy little TV and trying to pretend that he mattered."

Members of the Obama administration leaked a story to The New York Times last week saying the U.S. actually has stepped up operations against Qaeda-related groups in the midst of Yemen's chaos, "exploiting a growing power vacuum in the country to strike at militant suspects with armed drones and fighter jets." But some think the claim sounds suspiciously like an administration that's in the dark, whistling. "I think it's more signaling than fact," says Princeton University's Barbara Bodine, a former U.S. ambassador to Yemen. And in the meantime the chances of killing the wrong targets in such raids go up astronomically. "With the loss of intelligence cooperation with Yemen, we are trying to cut back the jihadis as much as possible," says terrorism expert Bruce Hoffman of Georgetown University. "But where it used to be surgical, it's now much blunter."

Over the long term, in fact, the key to defending Americans and U.S. interests from attacks by jihadists is either to insert spies into their organizations or to persuade people who are already inside to talk. Aerial surveillance and communications intercepts are useful, but solid information from human sources is vital, whether you're targeting specific terrorist leaders or trying to disrupt operations in other ways.

The Americans have spent long years building liaison relationships with key figures in the military and intelligence apparatuses of countries across the Middle East who might deliver that kind of detailed information. But now, says Christopher Boucek of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, "the Libyans, the Tunisians, the Egyptians, the Yemenis—they are either gone or going." And a particularly cruel irony, as a former CIA station chief in the Middle East points out, is that these relationships were so focused on catching a handful of terrorists that they missed the oncoming tidal wave of popular revolt. "What intelligence is supposed to do is be ready for things like this," he says.

The thought is underscored by Edward Walker, a former assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs who now teaches at Hamilton College in New York state. "We became far too overreliant on those networks," he says. "When you are totally dependent on local intelligence organizations, you tend to protect them." In the process America becomes blind to what the regime will not see.

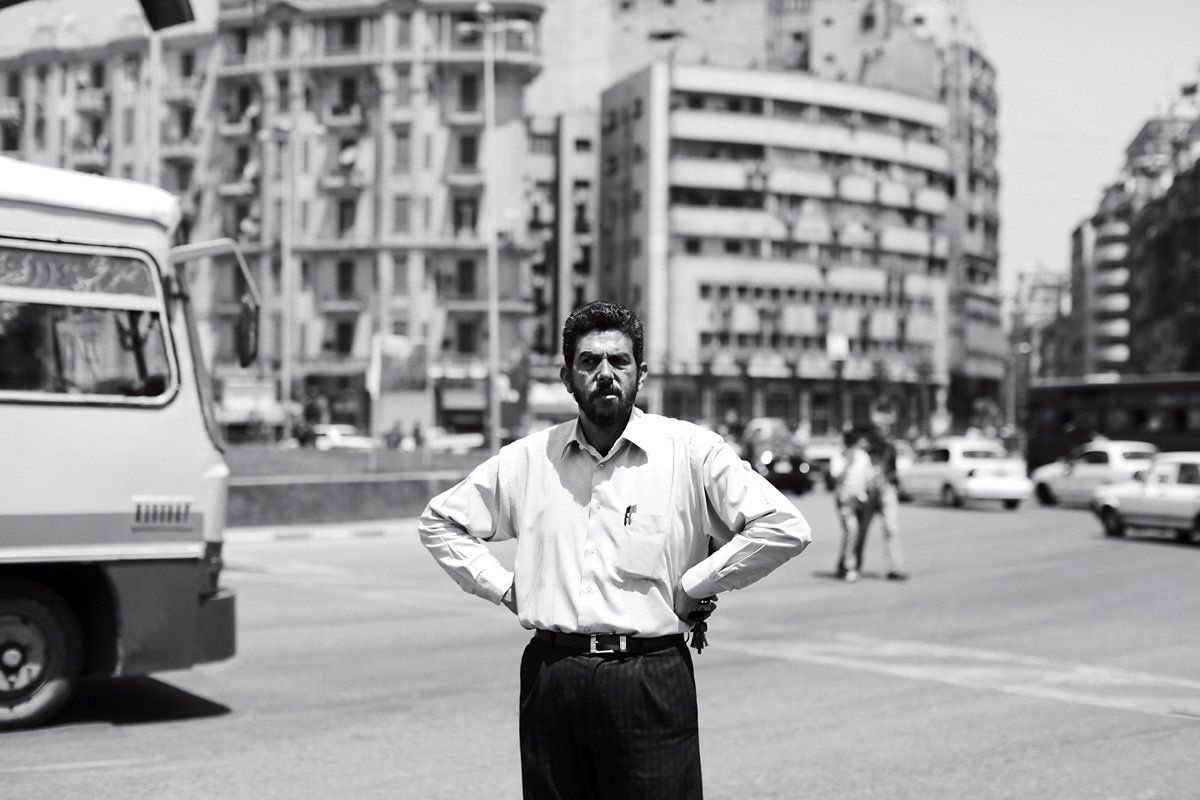

A quick tour of the counterterrorism horizon suggests just how unprepared the CIA, the Defense Department, and other U.S. government entities are for the post–Arab Spring world, and how hard it will be for them to rehabilitate their old techniques for fighting terrorism. For almost 30 years, U.S. intelligence relied on Hosni Mubarak's Egypt as a key ally, and the pivotal figure in that relationship was Gen. Omar Suleiman, director of the country's General Intelligence Services, commonly called the Mukhabarat. "He's philosophically Western and a cultured man, and he was a linchpin," says Mr. Mum.

The partnership became a top priority in the 1990s, when Egypt faced a serious terrorist threat led by Ayman al-Zawahiri—the man who eventually joined forces with Osama bin Laden to create what is now called Al Qaeda. In the Clinton years the CIA used its global reach to track down members of the organization, then sent them to Egypt for interrogation that often extended to torture and in some cases execution. From Egyptian jihadists picked up in Albania and elsewhere, the Mukhabarat and the CIA gleaned important information about the inner workings of Al Qaeda. But the United States compromised its moral standing by accepting "with a blink and a nod" Egyptian assurances that no torture would be employed, says Walker, who was the U.S. ambassador to Cairo at the time. In any event, the intelligence gathered wasn't enough to stop Al Qaeda's 2001 attacks on New York and Washington.

The "rendition" program continued in close cooperation with Suleiman after 9/11, but the Bush administration evidently pushed hard for the kind of intelligence it wanted rather than the kind it needed. One captured Qaeda operative, Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi, was tortured by the Egyptians until he confessed there were operational links between his organization and Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, although in fact there were no such links. "They were killing me," al-Libi was quoted as telling the FBI later. "I had to tell them something."

When the popular revolt against Mubarak hit Egypt this January, it caught everyone off guard, not only the octogenarian dictator himself but the CIA and even the Mukhabarat. It's not entirely the CIA's fault that it failed to see the approaching storm: for all the supposed cooperation, the Egyptians had always tried to prevent the Americans from investigating popular dissent inside Egypt. "There was a pretty clear line drawn," says Mr. Mum. Part of the price of cooperation against international terrorists was enforced ignorance about domestic unrest.

But when Mubarak fell, he took his longtime intelligence chief down with him. As the protests grew in Tahrir Square, the old man moved—with more than tacit approval from the United States—to name Suleiman his vice president and likely successor. But the crowds in the street refused to sit still for any such thing. Suleiman has been out of intelligence work, as well as politics, ever since. No one can say who might replace the ousted Mukhabarat chief as Egypt's link to the U.S., and it's not just a matter of his job title. "All intelligence liaison is based on personal connections," says Georgetown's Hoffman. "Before, you were working with people who were focused on the international terrorist threat and focused on their mission. Now, if they are focused at all, it's on the internal threat, and their mission is saving their jobs. And many of them will see having anything to do with the United States as toxic."

The disruption is even greater in Libya. British and American intelligence forged close ties in the 1990s with Tripoli's veteran spymaster, Moussa Koussa. The relationship became tighter still after 9/11 and played a vital part in Muammar Gaddafi's "rehabilitation" in Western eyes. Counterterrorism made strange bedfellows: Gaddafi was obsessed with stopping Libyan jihadists who had tried for decades to murder him and overthrow his regime. The U.S. was focused on the same group because Libya was the home country of many recruits to Al Qaeda's ranks in Afghanistan and Iraq. But early this year, Gaddafi suddenly released hundreds of hardened jihadist fighters from his jails, claiming they'd been rehabilitated. "We have no idea where they are," says Carnegie's Boucek, who interviewed some of them at the time. But when the popular revolt against Gaddafi began, America, Britain, and France took the lead in providing air support for the rebels. Koussa quickly defected to London, depriving the West of its No. 1 Libyan intelligence channel. And now there are reports out of Mali and Algeria that quantities of sophisticated weapons, including shoulder-held surface-to-air missiles, are making their way from looted Libyan arsenals into the hands of Qaeda factions deep in the desert.

The situation is no less precarious in Yemen. In recent years America has deployed advisers there, working to build up the elite counterterrorism unit of the country's Central Security Organization, commanded by a nephew of President Ali Abdullah Saleh. Last week the dictator was in Saudi Arabia, convalescing from injuries sustained in an explosion at his presidential compound on June 3, and he seemed likely to remain in exile. His relatives are still on the ground in Yemen, but at this point there's no way to say whether they will concentrate their firepower on anti-regime protesters, on rival tribes, on each other, or on all of the above. One thing seems certain: they probably won't expend much energy or ammunition against the jihadists who call themselves Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

The terrorist group isn't likely to seek out any such confrontation. The fact is that the wildly spreading instability that has accompanied the Arab Spring is custom-made for the jihadists' needs. "Al Qaeda thrives in weak or failing states, not failed states," says Boucek. "They are dependent on a certain amount of things working. They don't want to live totally off the grid. And the space that is best for them is a place where the central government is weak but not totally collapsed." At the moment, only a few of the Arab world's wealthiest monarchies—most notably Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates—seem to be safely outside the semifailing category.

Which is why the Americans have once again turned to Riyadh as their discreet and indispensable ally. In Yemen particularly, the Saudis have their own operatives on the ground and many tribal leaders on their payroll. The kingdom's main objective—to stabilize Yemen while eliminating Al Qaeda—is much the same as Washington's. But can Saudi Arabia really resist the region's seismic change? If the country is about to erupt as Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Syria have done, would local intelligence services know? Would the Americans? The record is far from encouraging.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.