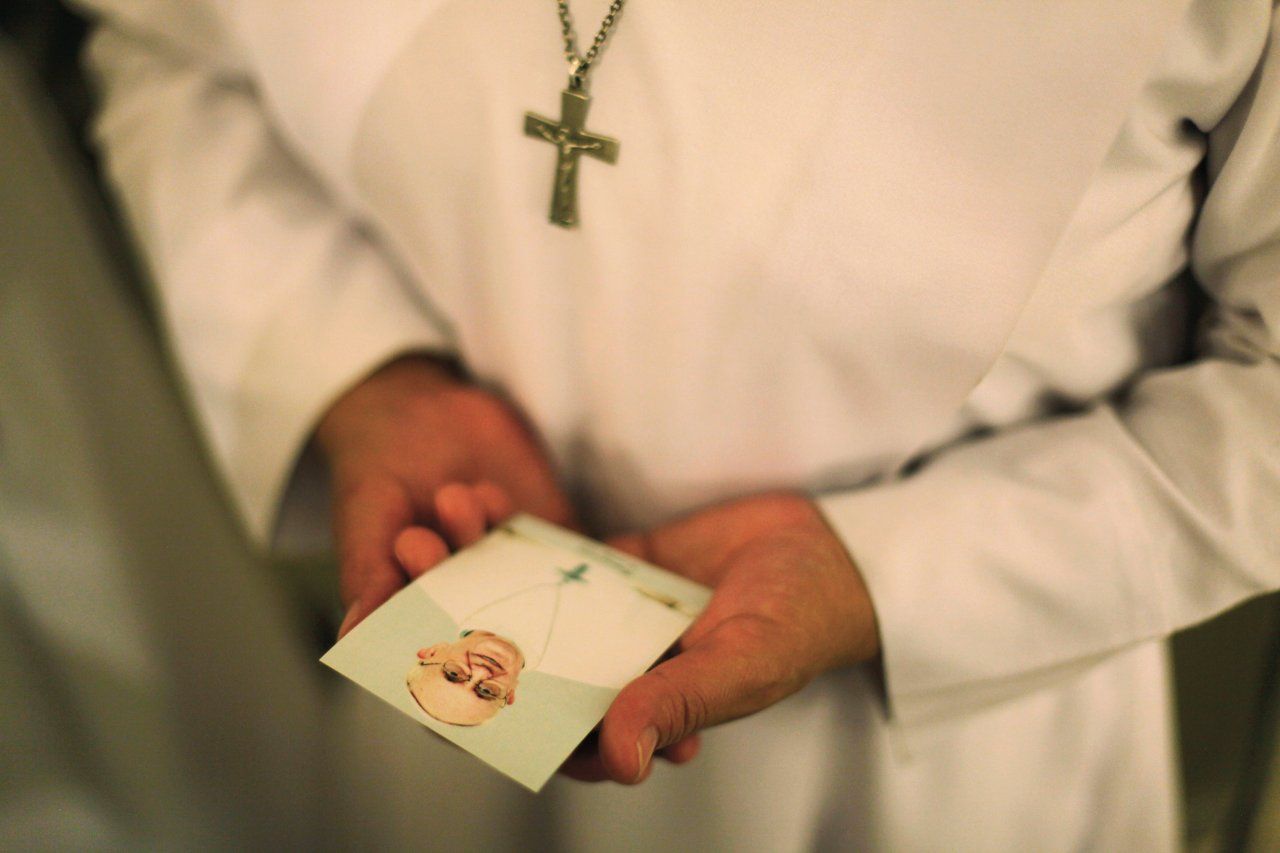

Newly enthroned, his papal whites barely wrinkled, Francis I has taken the Roman Catholic world by storm. Vaticanistas parse the pontiff's every gesture and genuflection, but the good will toward the new pope is hard to miss. "Humble," "simple," "unpretentious," and "a compassionate conservative" are a few of the characteristics he's been assigned, though it may be prayerful thinking. The fact is precious little of substance has been revealed about what the simpatico Argentine cleric actually believes.

Until now.

It turns out there's plenty to mine, and the best part is not locked away in church archives but spelled out in a series of conversations between Jorge Mario Bergoglio and his fellow Argentine, Rabbi Abraham Skorka. For 20 years, the archbishop of Buenos Aires and Skorka, leader of the Latin American Jewish Assembly, carried out a public conversation, parts of which aired on television. An edited version of their exchange Sobre el Cielo e la Tierra (On Heaven and Earth) was published in Spanish in 2010 and reissued last year by Random House.

But in the rush to interpret the new pope, few of the instant oracles have bothered to read it, it appears. It's a shame because On Heaven and Earth is a rich, nuanced conversation between two like-minded spiritual leaders, who also are close friends. The subjects—decanted from the decades-long dialogue—range from atheism and ecology to the Holocaust and the dirty war in Argentina, with asides on the philosophical musings of Saint Augustine, Maimonides, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and Karl Marx.

Though cordial to a fault—they appear to agree on everything—the exchange is packed with insights into Bergoglio's thinking, and many of the best passages stand out as a clear refutation to the facile labeling the Vatpack journalists have indulged in since white smoke first curled over the Sistine Chapel.

Bergoglio's positions are hardly those of a starched conservative. On matters of social justice and poverty, he sounds positively radical. A fierce critic of unbridled market forces—"savage capitalism" in his description—he lashes out at those who pay mere lip service to the poor, and admonishes clergy unwilling to "roll up their sleeves" and "muddy their feet" in service of the poor.

His attitudes on abortion and gay marriage are unsurprisingly orthodox. But as archbishop, Bergoglio showed flexibility. During an acrid debate in Argentina that threatened to divide church and country, he took a pragmatic stance, rejecting gay marriage but supporting same-sex civil unions. Nor, he says, can the church turn its back on divorced Christians. "The fact that someone has strayed from [God's] commandments doesn't erase the fact that they were baptized," he says.

He also is aware of Scripture's sand traps, such as the paradoxical biblical mandate to "dominate the earth," a prescription "for ecological problems."

What the book doesn't do is resolve the question of Bergoglio's conduct during the dirty war, when, between 1976 and 1983, a brutal military regime jailed, tortured, and "disappeared" tens of thousands of civilians. Critics allege that Bergoglio, then the country's ranking Jesuit, declined to intercede in favor of two young activist priests who were arrested and tortured. Bergoglio has denied he was complicit, but issued a collective apology in the name of the church for not doing more to defend the clergy under fire.

"There were sinners and saints, as in everything else," he says in the book of the church's role during the dictatorship. "I agree that there is much to investigate."

The book probably won't satisfy those who question Bergoglio's role during Argentina's darkest hour nor those seeking radical doctrinal change. But the Bergoglio who emerges in these pages is both intellectually provocative and refreshingly forthcoming.

As the new leader of an institution troubled by concealment, sex crimes, and half truths, this is an uplifting beginning.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.