Among china's greatest art treasures are the Buddhist caves near Dunhuang, an oasis on the fabled Silk Road that once linked China and Europe. Their ancient frescoes, sculptures, and other relics date as far back as A.D. 430 and have survived wars, environmental damage, antiquities hunters, and the chaotic Cultural Revolution. But their biggest threat today is tourism.

The UNESCO World Heritage site—which includes more than 700 caves, 2,400 clay sculptures, and 150,000 square feet of frescoes—has an optimal capacity of 3,000 people per day, but up to 8,000 visited the caves daily during holidays this year. The caves, also known as the Mogao Grottoes, have fragile ecosystems, and the buildup of humidity and carbon dioxide from visitors' breath can lead to flaking and discoloration of the delicate wall paintings.

In a bid to help preserve the caves, the Dunhuang Academy has settled on an innovative strategy: digitize them. The academy has been working with the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and Northwestern University to create a digital archive of the caves using a camera with a billion-pixel resolution. The results will be used in the academy's planned $40 million visitor center—slated for completion next year—which will present virtual tours of the caves to save the real sites from wear and tear. The scope of the project is daunting. It takes 20 minutes to record a 30-square-foot fresco, and there are 492 caves with murals inside.

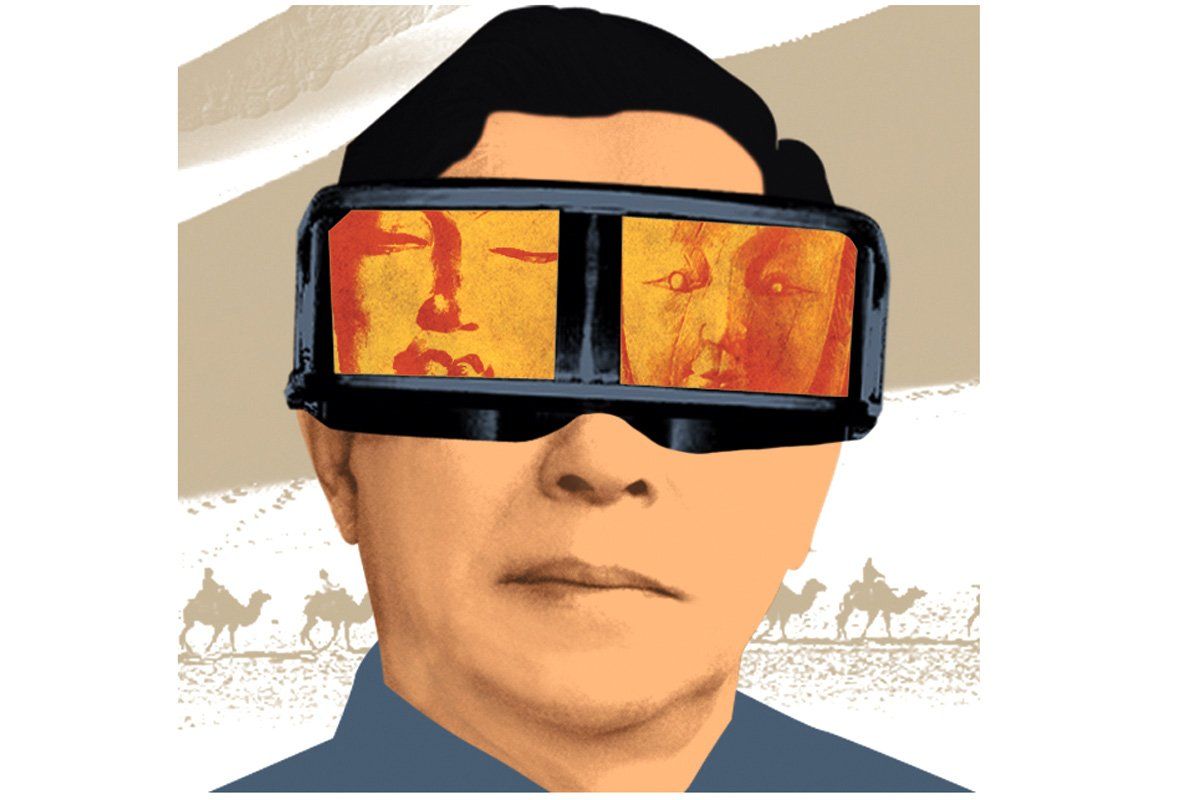

Recently the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C., offered a tantalizing glimpse of the final product. Donning 3-D glasses, visitors were transported across time and space into a "virtual" Dunhuang. The exhibit digitally re-created a single grotto, known as Cave 220, which boasts early Tang paintings from approximately A.D. 642. The 3-D, interactive experience is flooded with vivid color, entrancing close-up details, and moving images of flying bodhisattvas riding mythical animals.

One of the most popular features is the "magnifying glass," which can zoom in on, say, a zither depicted in a mural. The instrument appears to pop out of the wall, enlarge, and then rotate in space as zither music plays in the background. Visitors can also "flip" back and forth between an intricate Tang-dynasty mural and a later, cruder Sung-dynasty fresco, which had hidden the original painting until 1943.

To help bring Cave 220's Tang dancer paintings to life, performers from the Beijing Dance Academy were filmed by the City University of Hong Kong's Applied Laboratory for Interactive Visualization and Embodiment (ALiVE). They appeared in the Sackler tour dancing as if in midair, clad in brightly colored Tang period costume. ALiVE's project manager Leith Chan said that while he's become intimately familiar with the images of Cave 220, he hasn't been to Dunhuang yet. "I can't wait to visit the real thing."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.