Great white sharks might be able to change the color of their skin for camouflage.

In the new National Geographic Sharkfest documentary called Camo Sharks, Ryan Johnson, a shark biologist from South Africa, and Gibbs Kuguru, a shark geneticist from the Netherlands, work together to investigate whether great white sharks can change their color for camouflage and to blend into the environment, similar to other marine animals like octopuses or squid.

According to Johnson, the idea that white sharks could be a species that can modify the color of their skin came from years of working with them, and recognizing individuals that looked a slightly different hue to usual.

"I remember a time when we were looking at scars on the sharks to also help identify them, and then you realize, actually, that shark we caught was light [before] and is now dark, is in fact the same shark,'' he tells Newsweek. "That's when I sort of got the hunch that this was happening. But obviously, because of light conditions, changing weather conditions, swimming depths, it was never able to be [previously] proven."

In order to prove that the sharks were indeed changing color, there needed to be a control to compare. Johnson and Kuguru came up with a grayscale color board that they would attempt to photograph in the same frame as the sharks they were researching. Using Photoshop, they could then standardize the lighting conditions. This proved to be challenging, however, as sharks aren't the most cooperative models.

The researchers wanted to measure the color of the sharks as they breached, a hunting behavior, as well as when they were swimming at the top and scavenging at the bottom of the water column. To get the sharks to breach, they went to shark hotspot Seal Island off Cape Town, South Africa, and used a decoy seal as bait. For casual swimming behavior, they used a drone and a remotely controlled boat with the color board attached to get the board and the shark in the same frame, and for deeper waters, Johnson filmed the sharks in a dive cage.

"I think we're up to over 60 different recordings and visits from sharks," Johnson says. "Three or four that we've been working with most, we've seen over 20 times in the last six months."

Results from the color board tests seemed to indicate that individual sharks, identifiable by scars and other idiosyncratic traits, did indeed appear different colors in different scenarios, even when controlled for light conditions by the color board.

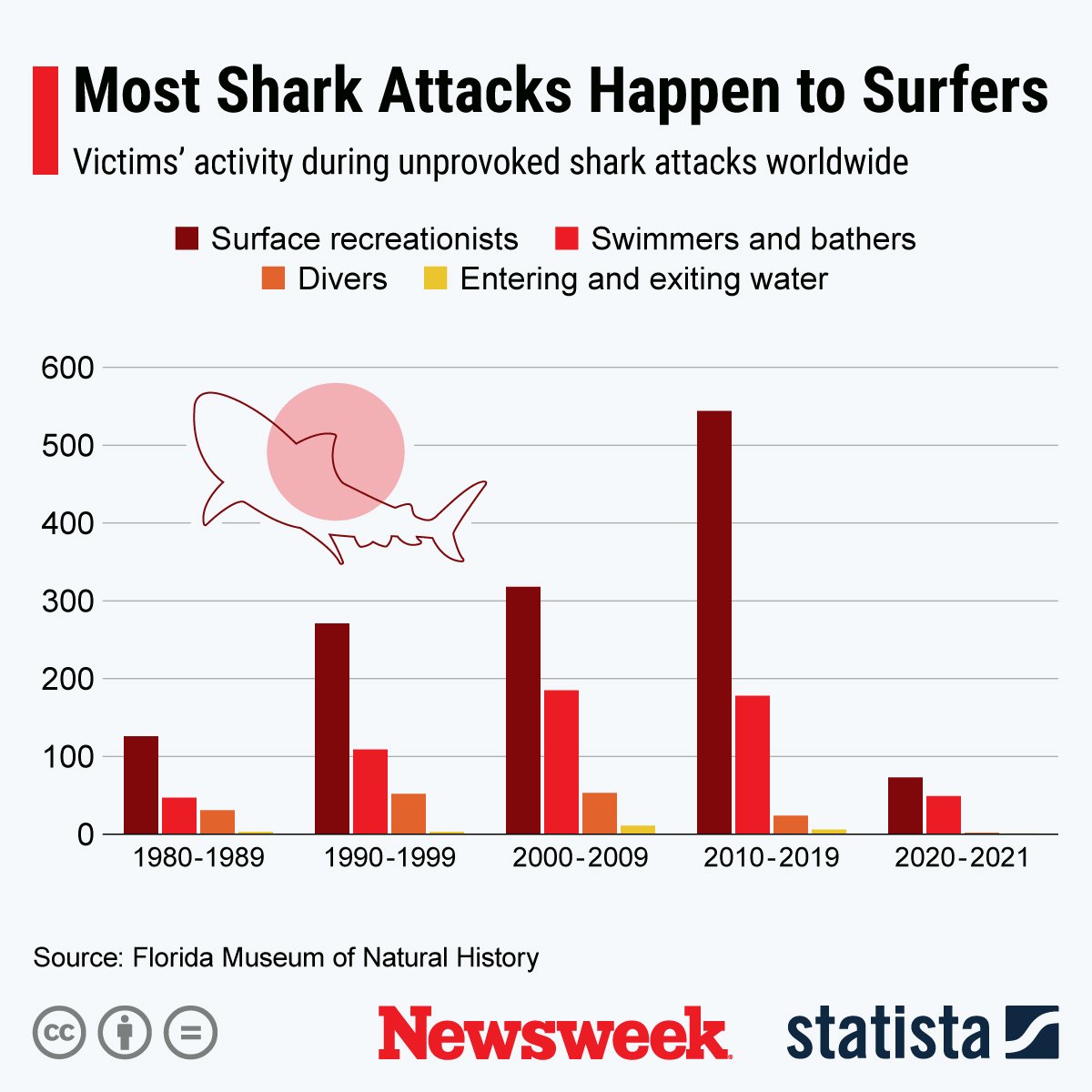

This chart, provided by Statista, shows victims' activity during unprovoked shark attacks worldwide.

"There was one shark in particular that came back on four or five occasions and we actually were able to track her in different situations. That was the shot during the production that I could analyze then, and actually use the color board to show that she changed color. But the subsequent sharks, we haven't analyzed yet. So we're planning to carry on with that research, at least for the rest of this year, because I want to see how different behavioral states actually control that," Johnson says.

The researchers also needed to prove that color change is scientifically possible for sharks, so they needed to investigate the skin cells for molecular proof. In species that are currently observed to change color easily, their skin cells contain melanocytes that produce melanin as the cell contracts.

To find out if the sharks could physically change color, the researchers planned to expose shark skin cells to various hormones: melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH), adrenaline, and melanin itself. They gathered skin cells from the sharks using a dart gun, and took them back to the lab.

To the researchers' surprise, when they exposed the shark cells to MSH, the melanocytes in the cells dispersed, making the tissue darker. When exposed to adrenaline, the tissue got lighter in color. Melatonin triggered the tissue to become a mixture of light and dark.

However, these results were from an extremely small sample size of three sharks. More data needs to be collected to make the results statistically sound.

"We need to do it clinically," Kuguru tells Newsweek. "I would say, based on what we've seen already, we wouldn't need many more individuals to complete the analyses. Between five to 15 samples for a whole sample set. It's worth realizing that we sub-sample each individual sample so that we test the hormone on each individual multiple times. So we will have potentially three to four times the amount of data from an individual shark."

While the results of the documentary aren't yet ready to publish in a peer-reviewed journal, the scientists are thrilled to get the opportunity to make a film about the research process, rather than just the results.

"This project was conceived from a hunch, and essentially National Geographic, which I'm eternally grateful for, had that faith to believe in this hunch, and put their resources behind it, allowing myself and Gibbs to go actually out and as we were making the documentary to do the scientific research, not knowing what the results were going to be," Johnson says. "So it was very organic, very stressful. But obviously, you know, we're still at a very early stage at getting the answers and having all the answers that we want."

Kuguru agrees, and felt that it was a special experience to go out and research an interesting idea that might not end up with world-saving or groundbreaking results.

"Oftentimes, with science, the research agenda is preset. So the fact that we got to go out and do this experiment: that's never been done before," Kuguru says. "In the old days, science used to be, "Hey, I have a super creative idea. Let me see." I feel like National Geographic has opened up this avenue for me as a scientist to just explore an idea that I didn't fathom before."

Camo Sharks kicks off Sharkfest July 10 at 10/9c on National Geographic.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more