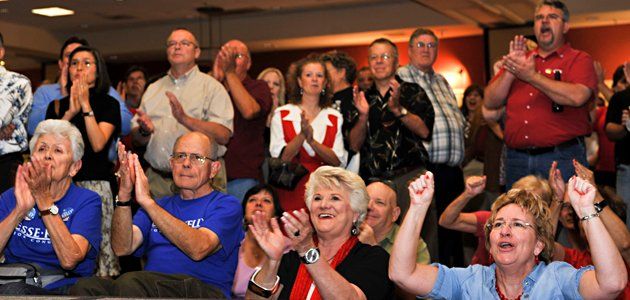

Despite what the cable coverage may suggest, the most consequential data point to emerge from Election Night 2010 wasn't Christine O'Donnell's defeat in Delaware. Or Linda McMahon's loss in Connecticut. Or even Rand Paul's victory in Kentucky. Instead, it was a single number buried deep in the exit polls: 23.

That's the percentage of voters Tuesday who were over 65 years of age, which explains a lot about how the Republican Party got here, and a lot about where it's going. The question now is whether this senior moment is a positive development for the GOP—or a sign of trouble ahead.

The first thing worth noting is that the number of seniors voting this year was extraordinarily high. Early in the night, many commentators made the mistake of marveling at the big jump

in turnout from 2008 to 2010. That's misleading. The geriatric set always makes up a disproportionate slice of the midterm electorate, so it's not really accurate to compare a midterm to a presidential election. But this year's slice was more like a hunk. In the last midterm elections, in 2006, over-65ers made up 19 percent of the voter pool; the same goes for 1994, the last time the GOP ran the board on a recently elected Democratic president. So this year's number—again, 23 percent—is a full 4 percentage points higher than the recent benchmarks. It was a historic night for early-birders.

And that's a major reason it was a historic night for the GOP. Obama has always had trouble with older voters; NEWSWEEK was writing about his handicap as early as April 2008. But after the initial excitement over his presidency wore off, seniors became a particularly glaring soft spot for Democrats. Sixty-three percent recently told New York Times/CBS News pollsters they were disappointed in Obama, and surveys have repeatedly shown that they "remain the group most resistant to Obama's health-care agenda and the most skeptical of him overall." As a result, Tuesday's exit polls showed that in contrast to 2006, when voters over 65 split their vote 49 percent to 49 percent between Democrats and the GOP, they now support Republicans 58–40, by far the largest pro-GOP margin of any age group. This means that retirees accounted for more than four of the estimated six percentage points that separated Republicans from Democrats in the national popular vote. The GOP has officially become the party of older people.

On Tuesday, this senior support helped Republican candidates get the results they wanted. But in the long run, it may prove to be a double-edged sword. It is difficult, for example, to fulfill your promises to balance the budget and reduce the national debt without enacting substantive reforms to Medicare and Social Security, and it's almost impossible to reform Medicare and Social Security if your most important constituents are the people who benefit the most from those programs. The result is a lot of hypocrisy—like Republicans resisting precisely the kind of Medicare cuts they've advocated for decades—and a potential split between spending-obsessed Tea Partiers and the establishment conservatives who know they owe their jobs to seniors.

And then there's the little problem of electoral math. Voters over 65 are, by nature, a dwindling voting bloc—unlike, say, minorities and younger voters, who tend to vote for Democrats (if more sporadically). The risk for Republicans, as Ron Brownstein has noted, is that "a strong 2010 showing based on a conservative appeal to apprehensive older whites will discourage [the GOP] from reconsidering whether its message is too narrow to attract those rapidly growing groups."

Chances are Republicans will be too busy celebrating Tuesday's big victory to ask any questions. That would be a mistake. Winning a single midterm election on the backs of disgruntled older voters in a time of severe economic anxiety is one thing. Basing your party's electoral future on seniors is something else entirely. If Republicans knew what was good for them, they'd start figuring out how to expand their reach beyond retirees before the next election rolls around.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.