Mention the name Gloria Steinem to many women under 30, and if there is a flash of recognition at all, they put her in Florence Nightingale's league—an admirable figure from the history books. To them, feminism was a war won before they were born, the miniskirted 1970s revolution that freed their mothers and grandmothers from drudgery and discrimination, paving the way for their own generation's unfettered freedom.

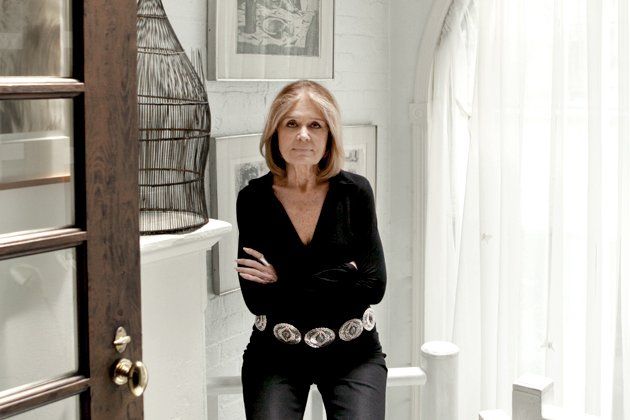

But in the living room of the funky Upper East Side duplex where she has lived for more than 35 years, Steinem, 77, is still on the front lines of a fight she considers barely half finished. Every day, the news pours in—from the Middle East, Africa, India, and Washington, D.C.—jamming her inbox and filling up her speaking schedule. The media haven't paid her much attention in the past 15 years (so many Kardashians, so little time), but the woman who has been the enduring face of feminism for nearly half a century insists her hands are as full as ever.

"Obviously we've come a long way on many fronts, at least for some women in this country," says the activist and founder of Ms.magazine as she curls her bare feet beneath her on a green velvet sofa she's had for decades, sipping a lukewarm cup of coffee and leaning against a needlepoint pillow that reads "Being on the Bestseller List Is the Best Revenge." "But then you have Anders Breivik," the Norwegian man who massacred 77 people in late July. "He was clearly motivated by woman-hating and the cult of masculinity. His own manifesto made super-clear that he hated his mother and stepmother for being feminists and 'feminizing' him, that feminists made 'men not men anymore.' How far have we come if that part of it barely got any coverage?"

Don't get her started on Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the former IMF chief who has been accused of sexual abuse by an African-born chambermaid assigned to clean his New York hotel suite. Even though the case may never be prosecuted because it is muddled by inconsistencies in the woman's story and background, Steinem considers the skirmish a victory. "Anyone can see this is a pattern of behavior," she says in her measured Midwestern tones, pointing to other women who have claimed Strauss-Kahn harassed them. "And now that has been exposed. He's gone from the job, disgraced. No matter what happens, it's a net win for us."

As for Michele Bachmann and Sarah Palin, women who wouldn't be riling up the Tea Party faithful had Steinem not paved their way out of the kitchen, she sees them as inevitable, as was (ERA opponent) Phyllis Schlafly at an earlier time. "You know what you're saying is important when the power structure brings in people who look like you and think like them."

Steinem's relentless focus, tidy theology, and talent for staying "on message" are what has enabled her to run the long race. Her rival, Betty Friedan, the fiery theorist whose 1963 book The Feminine Mystique jump-started the movement, burned out long before she died in 2006 at 85, and Germaine Greer, the Australian Marxist, is largely a footnote beyond the confines of women's-studies departments. Steinem may not be the ubiquitous cultural touchstone she once was, but she still speaks at dozens of college campuses, seminars, and community groups around the world each year.

The iconic aviator glasses have lately given way to rimless frames, but her longstanding belief that equality is a global issue—it was one of the points of friction between her and Friedan, who mostly concerned herself with the oppression of America's white middle-class married women—has been writ large in recent years. Such issues as human trafficking and genital mutilation, which she first wrote about in 1979, once evoked little interest in the mainstream. Yet post-9/11, even Americans have come around to her belief that it is folly to ignore repression abroad. Much of Mohamed Atta's rage came from being "ridiculed by this authoritarian lawyer father who told him that even his older sisters were more masculine than he," she says. "He became addicted to proving his masculinity. How clear is that?"

Steinem may soon be discovered by a new generation. Next week a documentary, Gloria Steinem: In Her Own Words, will debut on HBO. The film traces her life from her teenage years taking care of her mentally ill mother in rundown East Toledo, Ohio, to her early career as a trailblazing magazine writer in Mad Men–era New York and her 1963 undercover exposé of life as a Playboy Bunny. She recounts her feminist "conversion" at a 1968 abortion-rights rally and the founding of Ms. in 1971 in a one-room office littered with cardboard boxes. She even tap-dances, a skill she honed as a 10-year-old in the 1940s in smoke-filled music halls.

The film glosses over the more difficult issues, to be sure: Steinem's romantic relationships with influential men (JFK adviser Ted Sorensen, director Mike Nichols, media mogul Mort Zuckerman) that, to carping critics, undermined her "of the people" image; her decision not to have children; the 1990s backlash against the "political correctness" she was blamed for fomenting; how her father's obesity engendered in her an almost pathological fear of food that continues to this day.

On vivid display are the strengths that Steinem shows in person: her soothing tenacity and lack of ego, her rejection of pretentious academic language, a marathoner's even keel, her skill as a popularizer of difficult ideas. With her sloe-eyed glance and easy manner, she was sometimes accused by more radical feminists during the 1970s and '80s of being overly conciliatory. But her use of the carrot as well as the stick was undeniably effective in making the message palatable. ("How could you not love Norman Mailer?" she says, picking at a bowl of organic pistachios a friend brought from Iran. "He was a total chauvinist, but also so vulnerable.")

But Steinem has also been accused of ignoring cultural complexity. Her views, sculpted in the 1960s and largely unchanged, have drawn fire from those who say the modern world is more complicated than she thinks. In 1968 the veil that masked women in the developing world seemed as clear a target as a bullfighter's cape, an obvious sign of the patriarchal death grip. Now many young women in Europe and the Arab world insist that choosing the headscarf or hijab is a feminist issue. Sure, sex trafficking may be an obvious evil with virtually no defenders except those who stand to profit financially, and arresting Saudi women for driving provokes easy outrage. But genital mutilation has proved more intricate, with some factions—and even some women who have suffered the practice—arguing that it is cultural imperialism to oppose it. Yet Steinem remains unbowed, seeing it all as internalized repression. "It's heartbreaking," she says, "to watch people working against themselves."

The documentary fails to shed light on the intriguing contradictions in Steinem's persona. A master at creating instant intimacy, she remains a sphinx even after half a century in the klieg lights. While it is impossible to doubt her sincerity as she levels her warm, unhurried gaze, after nearly 50 years on the stump she has the practiced charm and seeming spontaneity of a skilled politician. Her tendency to turn even the most dispiriting event into a learning moment (among her four books is the 1992 The Revolution From Within: A Book of Self-Esteem, a hybrid memoir and self-help tome) can make her seem -superhuman, more placard than flesh. She mocks herself gently as a "hope-aholic," encapsulating both her optimism and her weakness for a peppy catchphrase.

Yet Steinem hasn't lost the urge or the ability to shock. In 2000 she married for the first time, at the age of 66. She and her husband, 59-year-old David Bale, a South African activist whose son is the actor Christian Bale, wed mostly for the sake of his immigration status, she says, but diehards accused her of betraying her reputation as single by choice. "People have to remember that the laws have changed, that marriage has changed," she says. "I was never against marriage per se. Before feminism, I didn't think you had any choice. In fact, for a long time I always assumed I would get married. I just didn't see any marriages I wanted to emulate, so I kept putting it off. Then, once I realized how bad the laws were, that you lost your name and had to go to court to get it back, it was obvious it didn't make sense. But that's not the case now."

In 2003, less than three years after the wedding, Bale died of brain cancer. The woman who had never lived with a man full-time, and feared having to take care of anyone as she had her own mother, wound up nursing him until the end. "It was actually very good for me," she says—as always, making sense and soundbites out of what might make others bitter. "It was as though life had given me a chance for a redo. Being an adult taking care of an adult was very different than being a child doing it." Could she have healed the scars of childhood by having a child herself? "Yes, I suppose I could have," she says, wavering a bit. "But I was always too young, not ready. By my 60s, I guess I was old enough."

Today she is single, happily. "I'm not lonely; in fact, I'm looking for loneliness," she says, laughing her famous laugh, as cozy as a pair of cashmere socks. But aging has not been without its pains, she concedes. Her 50s were rocky, emotionally. She "had been very defiant, thinking I would do -everything I had always done," an approach that led to burnout and a bout of depression. She spent a few years on billionaire Zuckerman's arm, a rare regret; he is the only one of her ex-lovers with whom she is not still friendly. ("Why did I go with it? I was tired. He was a great dancer and very funny. We just didn't have enough free time early on to realize we didn't agree on anything.")

Her 70s have been "surprisingly freeing." It is a relief, she says, no longer having her looks be such a central issue. While her prettiness was instrumental in getting her message across initially—it forced mainstream America to question the trope of feminists as unattractive man-haters—it was often a burden, she says. That many of her pals, including Marlo Thomas and Jane Fonda, have availed themselves of cosmetic surgery is a matter of public record; she has demurred. But, as always, she is careful not to publicly condemn the path of other women. "I'm lucky I don't make my living in front of the camera," she says, adding that her fear of bad surgery is far greater than her aversion to aging. "It's like a bad toupee. When someone's speaking, you can't think of anything else. For me, that kind of distraction would be a disaster."

As summer winds down and her autumn speaking schedule looms, Steinem struggles to finish her fifth book, about life on the road (working title: Road to the Heart). It's 15 years overdue. She deadpans that life on the road intervenes. And then there are the op-eds, statements of protest, and letters of solidarity to craft. (Her assistants are bugging her to start tweeting.) She claims that in her will she's leaving her apartment to "feminists, men or women, who need somewhere to stay when they're in New York." For now she hunkers down at the computer among the African artifacts. Soon she will gear up to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Anita Hill's run-in with Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas and prepare for a trip to Zambia.

"I think one of my problems is that I still have a hard time acknowledging age, accepting how little time remains," she says. "I mean, a new situation evolves somewhere in the world, something outrageous or troubling that really makes the point, and you feel you need to write about it, talk about it. There's progress, but it's much slower than people think. You never run out of things. At least I never do."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.