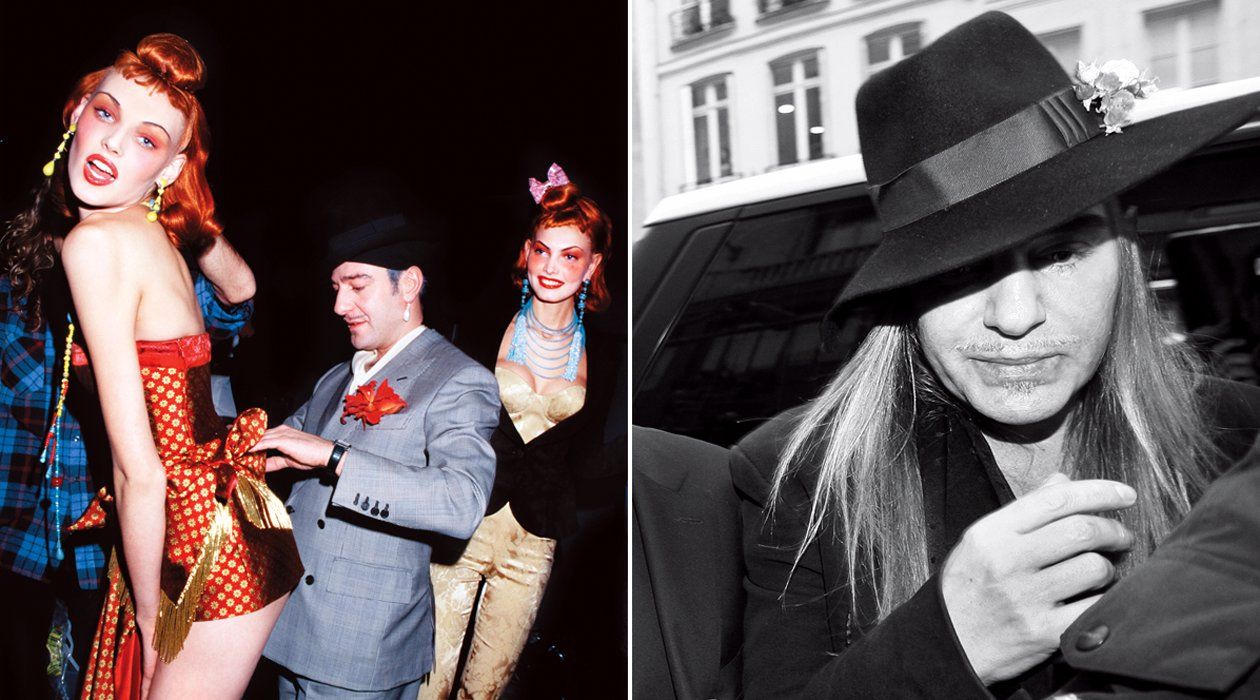

As John Galliano remembers the fateful February evening in Paris that destroyed his career, it began when the stranger at the sidewalk table next to him at La Perle café asked Dior's star designer, "Why don't you dress women like me?" As the woman herself remembers it, she had no idea who the longhaired man with the buccaneer look was. She thought he was homeless.

The scene turned very nasty very quickly. For the better part of an hour, Galliano allegedly tossed off anti-Semitic slurs and racist insults, as the café's other clientele tried not to hear. La Perle draws an arty crowd, but it has never gotten fancy: the counter is zinc, the décor has orange Formica accents, and the men's room offers only a bare hole in the floor, a squat toilet. To the extent it's chic, that's because the neighborhood around it—the Marais—has become so trendy. Galliano clearly felt he could say or do just about anything he wanted there.

But when the cops hauled him away that night and the world's media picked up on the story, an ugly history of just what he'd been saying and doing at that café began to surface. Another woman came forward to claim Galliano had called her a "f--king dirty Jew bitch" at La Perle four months earlier. Then someone sold a cell-phone video to a British tabloid showing Galliano, at his favorite battered table at La Perle, telling a couple of women he apparently thought were Jewish, "I love Hitler" and "People like you would be dead today. Your mothers, your forefathers, would all be f--king gassed."

In the eyes of his bosses at Christian Dior and the luxury conglomerate LVMH, Galliano might as well have plunged down the hole in La Perle's men's room. They fired him forthwith. When Dior CEO Sidney Toledano presented the house's prêt-à-porter collection—Galliano's collection—a few days later, he didn't even mention Galliano's name. The designer also lost the right to work for the Galliano clothing and accessories line, of which Dior owns 92 percent.

In the court of public opinion, Galliano was convicted without appeal. But this week, the tremulous 50-year-old from Gibraltar will have his day in a court of law. Making anti-Semitic or racist insults in France is a crime punishable by up to six months in prison and a fine of €22,500. A judge in Paris will be ruling on the facts of the case as laid out by investigators in a dossier that, under the French system, is shared by both the prosecution and the defense. NEWSWEEK has examined that confidential file in detail, and the story that emerges from it is not just a tale of hate, but also of fear and madness, compulsive self-indulgence and moral self-immolation. It's a tragedy that everyone around Galliano saw coming, but nobody could—or would—prevent.

The key event in the case isn't the scene in the vaguely sourced video, the origins and date of which are not well established, but the confrontation under La Perle's outdoor heat lamps the evening of Feb. 24. In the dossier, Galliano denies telling the woman at the next table, a 35-year-old art curator at the Arab World Institute in Paris named Géraldine Bloch, that she was "a dirty whore" with a "dirty Jewish face" and should die. For her part, the petite, pretty brunette alleges that Galliano pulled at her hair, made fun of her "revolting" eyebrows, and derided her "low-end boots and low-end thighs." And when the man with her, a 41-year-old receptionist named Philippe Virgitti, came to her defense, Galliano supposedly called him a "f--king Asian bastard" and "a dirty Asian s--t." (Another customer, a fashion student from Germany who was subsequently interviewed by police, said she heard Galliano ask the French-born Virgitti whether he had his papers, implying he might be an illegal immigrant.)

Days later, when police confronted Galliano with his accusers down at the station, as is normal practice in French prosecutions, not only did he contend he never said those things, he suggested he never would have. "How would I know she's Jewish?" According to the dossier, Galliano told the officer questioning him, "It isn't written on her forehead." (As a point of fact, according to her lawyer, Bloch isn't Jewish.) "It's clear that I'm neither a racist, nor an anti-Semite, nor a misogynist," the dossier quotes Galliano as saying. "It's possible this lady and her friend would like to profit from this chance [and] get some money and publicity in a sordid way." The facts suggest the contrary, since Bloch is asking only for a symbolic settlement of one euro and court costs, and her lawyer says her life has been seriously disrupted trying to hide from paparazzi and Galliano partisans.

It's apparent from the dossier that Galliano's recollections of that night are pretty vague, and it's clear why. After Virgitti threatened to hit him over the head with a chair, officers arrived on the scene and Galliano was hauled to the station. There, the report says, his eyes were glassy, his speech slurred. When they measured the alcohol on his breath, it came up four times the legal driving limit. Asked to explain, Galliano went back over his day: "I drank Champagne at lunch, during the afternoon I had a glass of Champagne while I did my shopping, I had dinner at a brasserie where I had some more Champagne, and finally at the La Perle bar I had a mojito." Later he said maybe he'd had some of a second mojito, too.

All this for a man who liked to make a big show of his fitness fanaticism as evidence he'd cleaned up his act. "I do not consume any drugs," he primly told the police. Galliano's defense is now expected to blame his behavior not only on the drinks that night but also on dueling addictions to booze and anti-anxiety medicine.

Galliano's promise has fallen prey to his appetites before. Early in his career, he developed a reputation for being a wildly eccentric and unpredictable party boy, with backers funding him and then abandoning him, again and again. By the early 1990s he was in Paris sleeping on the streets, literally, when Anna Wintour of Vogue rediscovered him and arranged for Galliano to put on a show that relaunched his career.

Bernard Arnault, the cool, strategic tycoon behind LVMH, decided to bet on Galliano as the man to bring fresh life into some of the company's classic couture brands—first Givenchy and then, in 1997, Dior. Galliano's designs were wild, with weird homages to gypsies and S&M, and they were très sexy. His creations boosted Dior's reputation, which in turn helped spur the hugely lucrative sales of perfumes and accessories, so that the house's revenues doubled to $312 million in just four years.

Galliano's efforts over those years to show that he was a reliable, disciplined, drug-free producer could be painful to behold. Joan Buck, the former editor in chief of French Vogue, remembers lunches with Galliano where "he was on excruciating best behavior. It was such good behavior it hurt my teeth."

Even so, Dior's Toledano, the corporate brain behind the company's success, rarely spoke to Galliano. The job of mediating between the two men and their two worlds fell to Galliano's close friend, Steven Robinson. When Robinson died suddenly in 2007, many of Galliano's admirers believe, the designer's personal decline began in earnest. His behavior grew more erratic, his tantrums all too predictable. The tension between Galliano and Toledano was exacerbated by what the designer saw as creative castration. With the global economy in free fall, Galliano's bosses had made it clear that he had to rein it in: hooker-chic was out; corporate couture was in. Even before the February incident, there was widespread speculation that Galliano's days at Dior were numbered. Neither Toledano nor any spokesman in his office would comment.

By the time Galliano got to La Perle that February night, his antics were so well known to the people who worked around him that when the "f--k you"s began to fly, his driver, watching from the sidelines, calmly called a lawyer and tried to put him on the phone with Bloch to calm her down or warn her off. She refused, and when she complained, a security guard told her it was Galliano and that she could just change seats, according to the dossier.

In the days that followed the incident, Galliano's friends tried hard to understand how the man they so often described as "sweet" could have spewed such repulsive, off-the-wall racist rhetoric. The alleged remarks are all the more offensive because of the venue in which they were made. The Marais used to be the center of Jewish life in Paris, but in the last 30 years it has become a gay haven popular with fashionistas. In the court dossier, Bloch and Virgitti say that during the argument they tried to calm Galliano down, but he kept insisting that they had to leave, that "the neighborhood belonged to him." It belongs at least as much to the history of the Holocaust: just a three-minute walk from La Perle is an elementary school where the Nazis rounded up 260 children and sent them to the death camps.

Some of Galliano's apologists think his rants were utterly incoherent, without any specific cause except to provoke, since provocation had always been his stock in trade as a designer and as a public personality. One infamous collection he presented for Dior was a paean to homeless chic, inspiring parody in the movie Zoolander, where a designer launches a line called "Derelicte." Others think his remarks were the twisted expression of hostility toward his boss Toledano, who is very proud of his Sephardic heritage. Still others say it may be self-loathing: Galliano reportedly told friends in the past that he thought he had Jewish blood in his own veins. But none of that can be confirmed in the dossier.

"The whole thing struck me as completely out of character," says Daphne Guinness, the British socialite and style setter. She sees an eerie parallel with the suicide last year of her friend, designer Alexander McQueen. In Galliano's case, "He was drunk and isolated and looking for the most outrageous thing he could say, and instead of hanging himself, he just said something," she said. "Maybe he has a secret stash of Nazi uniforms, but I just don't think so."

With Jacob Bernstein and Tom Sykes

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.