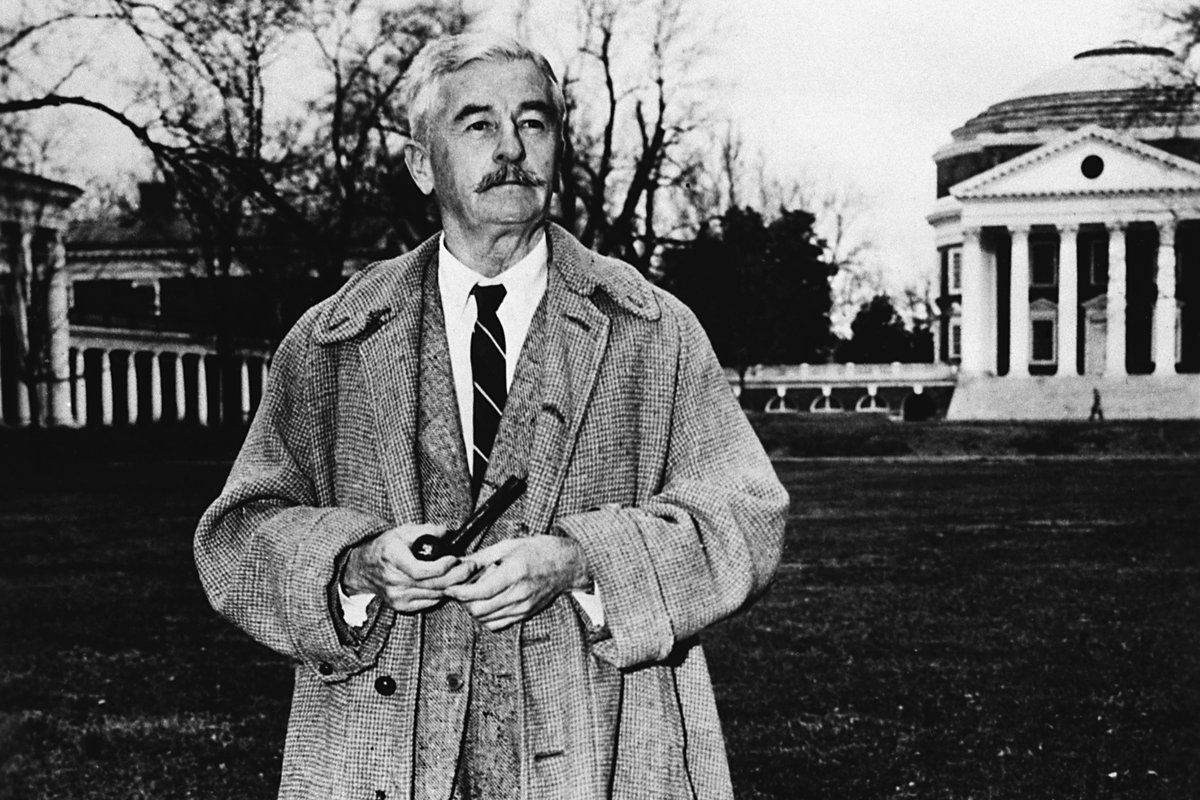

Faulkner speaks! Fifty years after he spent two years as writer in residence at the University of Virginia, the school has posted online recordings of the two addresses, the dozen readings, and the 1,400 questions that students, faculty, and interested townspeople of Charlottesville, Va., posed to the author. For Faulkner fans, these 28 hours of talking and reading are Christmas in July.

Apart from brief stints in New Orleans, New York City, and Europe, Faulkner lived in only two places, Oxford, Miss., and Charlottesville, Va. He must have liked college towns. In Oxford, where he grew up and lived for most of his 64 years, he was mostly taken for granted, ignored, or joked about. Count No 'Count was his local nickname. In Charlottesville, he was treated like royalty, and that, combined with the facts that his daughter lived there and that he loved the local hunting scene (pink jackets, bugling, and riding to hounds), surely influenced his wish, cut short by his death, to move to Charlottesville permanently. Given the warm reception he got there, so audible on these recordings, it's easy to see why.

A harder-nosed critic might argue that these recordings are nice, but do they really add that much to what we know about the books, which are, to be sure, the important things first and last? All I can say in response is that when it comes to one of America's greatest writers, I want to know all I can about how he lived, what he wrote, and what he thought about it all. Listening to his voice on these recordings, listening to him think out loud, I learned a lot.

When I was a teenager, I became addicted to Faulkner's stories and novels. It was then my habit, when I liked a writer, to read everything he or she wrote. With someone as prolific as Faulkner, that took some doing, but I persevered. What I was not able to do was to find out much about the man himself. There was lots of criticism available, but none of the major biographies were published then, in the late '60s. At some point, though, I stumbled across a paperback called Faulkner in the University, a collection of the classroom interviews conducted with the author at the University of Virginia from 1957 to '58. I read my first copy of that book until it came apart in my hands.

Here he was, talking freely about his work and his work habits. No one in that time and place would have thought to pry into his personal life, but I hardly noticed, because he was so forthcoming about his work. It was the first chance I'd ever had to hear how a writer thought about what he did. In Faulkner's case, the lesson was simple and pure: he thought about his characters as though they were real. In his mind, and he seemed not the least bit coy or fanciful about this, he was not creating a world, he was reporting on it.

Everyone was polite. The students were respectful but not servile—the greatest evidence of their respect was how well prepared they were. For his part, Faulkner was unvaryingly courtly and treated every question, no matter how naive, with serious consideration. Even as a teenager, though, I recognized that there was more than a little ham in the man. I'd spent most of my life in classrooms at that age, and if I had any expertise under my belt, it lay in knowing how various teachers worked a room. I'd never seen anyone who could match Faulkner. He answered the questions he wanted to answer, no matter what had been asked. He maintained a thrilling balancing act, tacitly acknowledging that his achievement was real and significant (he'd won the Nobel by this time) but managing at the same time to suggest a deference in his answers. He spoke as a no-nonsense craftsman who took pride in his tools and an honest job of work, and if you wanted to call him a great artist or a genius, well, that was your business. It was quite a show.

I went back to Faulkner in the University over and over. I reveled in learning his favorite books (Don Quixote, a lot of Conrad, Moby Dick, the Old Testament) and his habit, as he grew older, of going back to certain novels merely to keep company with particular characters. He was very fond, I remember, of Dickens's Mrs. Sarah Gamp, the umbrella-brandishing woman with the imaginary friend who confirms all her opinions in Martin Chuzzlewit.

Faulkner in the University was a revelation to me, because I knew no authors. From my perch in Nowheresville, N.C., as I thought of it then, I had to imagine the literary life pretty much from scratch. That book of interviews made a big world a little smaller, because here was a great author who made great literature seem a little less daunting. There was no tetchiness in his responses, but again and again, he plainly implied that he was not talking as a scholar but an author, and while he was, as he once put it, "sole owner and proprietor" of what he'd made, he was not there to explain it all away, that it could not be explained or illuminated any better than he already had in the books. He wasn't being naive or simple. He was merely saying that he thought differently about his work than a scholar would.

It was in this spirit that he said that it was all right to think of characters as people, to not worry too much about symbolism, and to be suspicious of ideas in fiction.

Question: Sir, to what extent are you—were you trying to picture the South or Southern civilization as a whole, rather than just Mississippi, or were you?

Faulkner: Not at all. I was trying to talk about people, using the only tool I knew, which was the country that I knew. No, I wasn't trying to—to—wasn't writing sociology at all [audience laughter]. I was just trying to write about people, which to me are the important [. . . ]. Just the human heart. It's not—not ideas. I don't know anything about ideas, don't have much confidence in them.

What I couldn't do, reading that book, was hear how he said what he said. There was no intonation, there were no pauses, there were only the words on the page, and while I devoured them, that was as far as I could go. Of course, at the time it never occurred to me that I could go farther, that a book of classroom interviews had to have a taped source. I didn't know what I was missing. Now I do.

Even in a world where we're drowning in information and have our attention tugged a thousand ways from Sunday, it can only be a good thing to have these recordings so readily available. Even a bookish 16-year-old kid, 50 times more sophisticated than I was at that age, can't help but know that.

In a soft-spoken and not so much slow as thoughtful drawl punctuated frequently by long pauses (the man who wouldn't let his teenage daughter have a radio in her bedroom was no stranger to silence), he answers questions both complex and simple-minded with equal amounts of patience, wit, and diligence. Some of his answers are canned (he'd been a fairly public figure since winning the Nobel in 1949 and thus had plenty of time to polish up his answers to the usual questions of how he came to write and what he thought of Ernest Hemingway, etc.). Most of his responses, though, are unrehearsed, and sometimes he almost gets excited, as when he's trying to remember why one character doesn't call another in a poker game in Go Down, Moses. Most of the time, it sounds like he's enjoying himself, and this is an impression that can only be formulated by listening to the recordings. He sounds pleased, but never smug, as though he's delighted to be there. Having only begun to tap these 28 hours of talk, I can see I have a lot to learn all over again.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.