The Mughal empire's most famous legacy is the monumental architecture with which it stamped its rule across South Asia. But the fitting centerpiece of an intimate show filled with ravishing miniature paintings is a jade terrapin, 15 inches long. Found in a water tank in Allahabad, India, in 1803 by a lieutenant in the Bengal Engineers, the exquisite creature is believed to have been made two centuries earlier for the Emperor Jahangir, a dedicated patron of art that mirrored the natural world.

Jahangir, whose son Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal, is among the six "Great Mughals" who dominate scholarship and displays about one of the world's most magnificent dynasties, with its heyday in the 16th and 17th centuries. Mughal India: Art, Culture and Empire, the major fall exhibit at the British Library in London, which runs until April, is rare in spanning the entire arc of the empire. Its 15 major emperors ruled from 1526, when the Turkic-Mongol prince Babur from Samarqand conquered the sultan of Delhi at the Battle of Panipat, to 1858, when the emperor and poet Bahadur Shah II was exiled to Burma after the 1857 Uprising—known to the British as the Indian Mutiny.

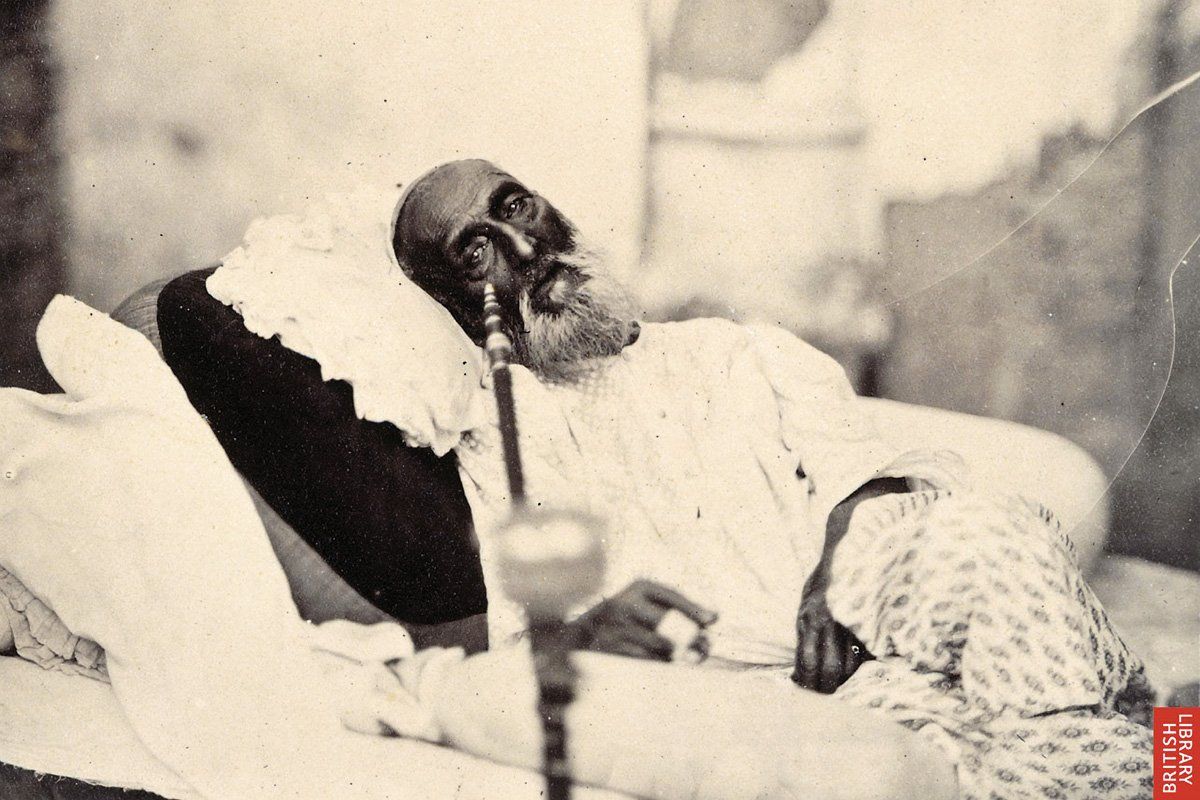

The images move from brutal battles and beheadings in an expansionist era, to a poignant photograph of the imprisoned last emperor, fatigued on a bed, awaiting trial by the British for treason. Like the Medici in Renaissance Florence, the Mughals combined statecraft and martial prowess—not least the savvy deployment of gunpowder and elephants—with a passion for knowledge and the arts. According to a Dutch traveler who marveled at its 24,000 volumes, the Emperor Akbar's library was worth as much in rupees as his armory.

An animated map in the exhibit shows the empire expanding from Kabul and Lahore to Calcutta, then shriveling until the last emperors were confined to a corner of Delhi. As Malini Roy, curator of visual arts at the British Library, tells me, her aim was to chart the "rise and decline of power" along with the eclectic culture that thrived through imperial patronage. On display are more than 200 paintings and manuscripts, including the "Johnson albums" amassed in the late 18th century by an East India Company official.

Namas, or illustrated chronicles of the emperors' reigns, are the most precious sources, painted with opaque watercolors in sumptuous mineral and earth pigments. Borrowed objects—such as the last emperor's bejeweled gold crown, sold to Queen Victoria by the Bengal infantryman who nabbed it at auction (and now on royal loan)—form illuminating correspondences with the art. The peacock feathers missing from a gem-encrusted jade morchhal (flywhisk) spray from its twin in a portrait of Bahadur Shah II smoking an improbably elaborate hookah.

Designed like a garden, a passion of Babur's, the exhibit has an intriguing central section on the emperors and their personalities, while outlying displays range from court life to religion and science. The dynastic founders vaunted their descent from Genghis Khan and Timur (Tamerlane), depicting themselves at Timur's feet. Babur's son Humayun died after falling down the stairs of a cherished library, but others perished in fierce succession wars—blinded or poisoned. Jahangir, the nature lover addled by opium and wine, set up a rival court in Allahabad to his father Akbar's, and was found by King James I's ambassador to be "very merrie and joyfull." A century on, Muhammed Shah, the "pleasure lover," is pictured in flagrant coitus on a four-poster bed. But there are also humbler records, such as the memoirs of Humayun's servant Jauhar, or a pigeon-fancier's poetic manual. Among gorgeous miniatures are A Young Nobleman Enjoying the Festival of Holi With His Consort" (1760), a sensuous riot of red and yellow, and Squirrels in a Plane Tree, (1605-08) a masterpiece of naturalism by Abu'l Hasan, an artist given the title of the "Wonder of the Age."

In an Islamic dynasty ruling over a Hindu-majority multifaith empire, Akbar forged a Mughal tradition of religious tolerance, holding interfaith debates and espousing a "universal religion." Akbar Ordering the Slaughter to Cease (1578), from the Akbarnama, shows the emperor in a moment of spiritual insight, stopping a cruel hunt. But he was also shrewd, winning over Hindu Rajput kingdoms with strategic intermarriages. The jizya, a poll tax levied on non-Muslims, was abolished during his rule, then reinstated by Shah Jahan's son Aurangzeb, purveyor of a more austere Islamic supremacy, under whom art patronage withered.

Strong sections on painting and literature reveal how Mughal art evolved from Persian and Indian cultures. Humayun brought Iranian artists to court, while his son Akbar gave them a formal artistic studio to lead, with Muslim and Hindu artists and calligraphers from across the subcontinent.

Completed in 1577, the Hamzanama's 1,400 paintings took 15 years and created a unified style. Elements of perspective were gleaned from Westerners, such as Portuguese Jesuits from Goa who came to spy on the court. Far from figurative art being forbidden, Akbar said that when a painter "draws a living being he must ...perforce give thought to the miracle wrought by the Creator."

The founding Mughals spoke the Turkic language Chaghtai, but Persian became the language of the court—and these manuscripts. There were sometimes more Persian books produced in India than in Iran. Rather like the Arabs, whose transmission of ancient Greek texts helped spur Europe's Renaissance, the Mughals were omnivorous translators. The Mughals were also omnivorous translators. In the 1590s, Akbar not only ordered his grandfather's memoir, the Baburnama, to be translated from Turkish, but he commissioned the Razmnama, or Book of Battles, a Persian version of the Hindu epic the Mahabharata—complete with paintings of the blue god Krishna. The Upanishads, the basis of Hindu philosophy, were introduced to the West not in Sanskrit but in the Persian ordered by Shah Jahan's son, who aspired to reconcile Hindu and Muslim doctrines.

In a blow to the declining empire, the Afghan invader Nadir Shah stole the gold Peacock Throne in 1739, also ransacking libraries. But as Mughal patronage declined, artists found other backers, turning to more literal studies such as the Pangolin painted in 1779 for Lady Mary Impey, to document her Calcutta menagerie. By the time the jade terrapin was found, the Mughal empire had shrunk to the confines of the Red Fort in Delhi. But its splendor still dazzles.

Maya Jaggi is a cultural journalist and critic in London whose award-winning writing ranges from global literature and cultural comment to travel. She is chair of the 2012 Man Asian Literary Prize.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.