One of the greatest challenges of driving in Egypt is knowing when to stop at a stoplight. Cars flood past the red signals as if they weren't there, and earlier this month on the way to see Mohamed ElBaradei, the man of the moment in Egyptian politics, I asked my taxi driver what the trick was. "You stop when you see the police," he said, as if that ought to be obvious.

For generations, Egypt and virtually all other countries in the Arab world have been ruled as if that same principle applied to every aspect of society: the people are bent on chaos and only the iron hand of a police state can impose order. The result, after decades under the all-seeing eye of the security services, is a pervasive atmosphere of political intimidation—and stagnation. "The government makes people feel they should be thankful they are being governed," says ElBaradei, best known for winning the Nobel Peace Prize as head of the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna. "I would be happy if I could stir the water a little, make it move."

In fact, ElBaradei is trying to do much more than that. His design is to lead a mass movement for change that will force the government to jettison the draconian Emergency Law in place since 1981 and open up the political system in other ways that will ensure next year's presidential election is free and fair. Then—and only then—the 67-year-old ElBaradei might present himself as a candidate and ride the wave of popular enthusiasm right into the presidential palace.

ElBaradei has chosen the moment well. Egypt is on the cusp of dramatic change whether it's ready for it or not. President Hosni Mubarak, after almost three decades in power, has begun to show his 81 years. When he had a procedure in Germany earlier this year to remove his gallbladder and a growth on his small intestine, he was out of touch for long enough that people thought he might have died. He may or may not run for a sixth term next year. And, not to put too fine a point on it, he may or may not live that long. Mubarak has never yet named a vice president. So no one is sure who will succeed him in the long term.

Meanwhile, political opposition—fueled by educated, frustrated young people and facilitated by the Internet—has grown dramatically, if haphazardly, over the last decade. The credibility of Mubarak's 46-year-old son Gamal as heir apparent is in decline amid widespread feelings that he's smart, handsome, and sophisticated, but utterly uncharismatic. Some military man may be waiting in the wings—but which one? Gen. Omar Suleiman is the name most often mentioned, and for good reason: he is the head of the Mukhabarat, Egypt's most powerful intelligence service.

This is all very new for a country used to having its pharaohs, and it's disconcerting for Egypt's allies. Mubarak's regime has been propped up for decades by hundreds of millions of dollars a year in development assistance and well over $1 billion a year in military aid from Washington. That was a reward for its 1979 deal with Israel, which relies on Egypt to keep the peace. But Egypt's stability and its commitments can no longer be taken for granted, as they have been for most of the last two decades, and the way Egypt navigates the potential chaos of the next few years could well set the course for the rest of the region.

So accustomed have we become to Egypt's torpor that it's easy to forget just how much weight it really carries in Arab culture and politics. Its population of more than 80 million is greater than Iraq, Syria, and Saudi Arabia combined. It could continue to try to muddle along on the same stagnant track with someone from the Mubarak establishment; it could slide toward chaos or Islamization, or have order imposed by a military regime like the one that ran Pakistan for most of the last decade. Or Egypt could actually start to lead the way toward a more democratic and progressive future for the whole Arab world. That's where ElBaradei hopes to take it, and where his supporters pray they are heading.

These are nervous times, certainly, for anyone afraid of change. At the elegant bar of the Four Seasons Nile Plaza hotel in Cairo, the fin de règne mood hangs as heavy in the air as the smoke from Cuban cigars. For those with money, the country has never been so luxurious or so efficient; foreign investors continue to come, and the stock market continues to rise. But not much of that money trickles down, and the gap between rich and poor grows more striking every day. Twenty years ago, wealthy Cairenes lived among the people downtown or in nearby suburbs. Today they are secluded in gated communities—what ElBaradei calls "ghettos for the rich"—around golf courses built in the desert. Even among a group of businessmen with close ties to the government I heard grim speculation, over glasses of Spanish wine and plates of risotto, about some unseen, bloody revolution brewing among "the 60 million": that three fourths of the population living in misery or on the edge of it.

There have been real revolutionary movements in the past. Radical Islamists murdered President Anwar Sadat in 1981, and Ayman al-Zawahiri, a member of that conspiracy, led a group known as Jamaa al-Islamiya in a terrorist campaign against the regime that lasted into the mid-1990s. After the government repressed, infiltrated, and obliterated his organization, Zawahiri fled the country to become, eventually, Osama bin Laden's deputy and the man who actually runs Al Qaeda.

But most opposition groups are far less threatening. Indeed, the great paradox of the Egyptian police state lies in its long record cultivating a certain level of tame extremism—which it finds useful to justify its police tactics—while it crushes passionate moderation. It's a cliché of Egyptian political commentary that if Mubarak did not have the Muslim Brotherhood to oppose him, he'd have to invent it. And ElBaradei has walked right into the middle of this political twilight zone.

The Mubarak government allows about 90 members of the "outlawed" Brotherhood to serve as "independents" in Parliament, where, with 20 percent of the votes, they make up the single largest opposition group. The Brotherhood, for its part, plays any angle it can, and has glommed onto the strongly secular ElBaradei. "I didn't know a single Muslim Brother until I came [back] here. But the head of the Brothers' parliamentary faction, Mohamed Saad el-Katatni, has come to my house a couple of times," says ElBaradei, who adds that he was reassured when el-Katatni declared, "We are for a civil state, we are for democracy."

Writing on Foreign Policy's Web site, Ilan Berman of the conservative American Foreign Policy Council in Washington suggests the Brotherhood is just using ElBaradei for political cover while continuing to push a radical agenda. "ElBaradei has begun a dangerous flirtation with Egypt's main Islamist movement," writes Berman. But ElBaradei says he has no illusions. "Of course there is a lot of suspicion about them," he says. "But I believe in a policy of inclusion to empower the moderates. Exclude them and you get the hardliners." In any case, he says, "I cannot ignore them. They have a lot of credibility in the street."

Meanwhile, Egypt's desperate moderates are taking the heat. Members of groups like the April 6 Movement and Kifaya, who were agitating for an end to the Emergency Law and constitutional reforms to open up the system long before ElBaradei's return to Cairo, have faced arrest, torture, and prison time. When a few hundred demonstrated in downtown Cairo earlier this month, truncheon-wielding police cracked heads and broke the bones of women and men alike before dragging scores away to jail. "No one will hurt ElBaradei," said a prominent moderate opposition figure who asked not to be named for fear of government reprisals, "but many of the people who support him are going to get hurt." ElBaradei himself was not at the protests, but condemned the violence on Twitter: "Detentions and beatings during peaceful demonstration is an insult to the dignity of every Egyptian. Shame."

At ElBaradei's house in a gated community near the Pyramids a few days ago, he was relaxed and funny. His bald head and his glasses have caused some admirers to compare his looks to Mahatma Gandhi's, but his Ralph Lauren pullover and penny loafers without socks don't quite fit that image. He had just retired from the IAEA last fall to write his memoirs and lecture around the world on such hot topics as disarmament and Iranian nukes when he found himself the focus of so much long-repressed hope for change in his homeland that he could not, or at least did not, resist the call to speak out against the government. "The first thing is to say the emperor has no clothes," he told me.

Among the intelligentsia and the young, he's hailed as a dream come true. A fan site set up for him on Facebook now has more than 100,000 members. "I was born when Hosni Mubarak was president and until now he's still president," says Abeer Soliman, who comes from a working-class family and writes an edgy blog about being a single woman. "For the first time we find someone who is brave enough, with such international credibility, that they can do something."

But the "something" he is trying to do is not what many Egyptians expect. Historically, theirs is a stunningly passive political culture. From the time of Alexander the Great until the rise of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the country was governed by Greeks, Romans, warriors from the Caucasus, Albanians—never an Egyptian. The history of pharaohs, kings, and tyrants goes back so far that, naturally, "people are looking for a leader," says veteran politician and activist Mona Makram-Ebeid. "They're looking for a savior." ElBaradei says that's precisely the mentality he's trying to change. "The pharaonic style of government, where you have a savior and you sit down and just watch—this is not going to happen," he says.

Out on the street, in fact, it's hard to judge just how much momentum ElBaradei's campaign really has. When he visited the city of Mansura in the Nile Delta recently, all the hopes and contradictions he's inspired were on show. And so was the government's ability to manipulate the system against him: the police prudently kept a low profile—they're not going to make him a martyr—but the university gates were locked and no El-Baradei supporters were allowed to enter; the prayer leader in the mosque where ElBaradei went to worship was imported from Cairo to preach obedience to power.

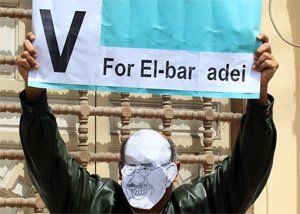

ElBaradei walked a couple of blocks through town surrounded by the crush of a few hundred supporters, but he gave no speech lest he be charged with illegal assembly under the Emergency Law. ("We are very 'virtuous' about such things," he told me afterward.) His strategy was just to be there drawing attention while young supporters tried to collect signatures. Some women wore ElBaradei T shirts with his trademark glasses and mustache printed on them; some carried ElBaradei paper masks. But they soon discovered that the peasant farmers on the edges of the crowd, the fellaheen, had mostly never heard of Mohamed ElBaradei, while many of those who had were afraid to put down their full names in support of his campaign. "The ghost that haunts Egypt is the police," said Amr Abbas, 27, an engineer from the nearby city of Sharqiya. "People tell you that you have to accept the system or you will be crushed by the police. People don't want to sign or protest. They say, 'I have children, I have a wife.' But how else will change come?"

Wilaa el-Abasy, a 22-year-old student who wears the black niqab, which covers a woman from head to foot and reveals only her eyes, laughed when a friend claimed to have gotten 60 signatures over the previous few days. "I couldn't collect that much," she said. "I got less than 10, and they were all my relatives. Everybody else I asked was frightened." But she still had hope, she said, because she had to have it. "All we want is good elections from glass boxes," she said, meaning ones where the number of ballot papers are there for all to see.

ElBaradei knows that to make that happen, he has to build enough public confidence in the power of a mass movement to defeat the climate of fear, then move on from there. But as things stand, his chances of getting on the ballot himself next year are diminishing day by day under the present constitutional system, which is designed to favor only the current regime and official opposition. ElBaradei says he doesn't want to legitimize the Mubarak government by running against its candidate in 2011—whether Hosni himself, his son Gamal, or some other handpicked successor—if the rules are not changed. If they stay as they are, ElBaradei will call for a boycott.

In the meantime, the loose coalition of opposition figures that came together around him earlier in the year will be prone to fractures. Already Ayman Nour, who ran against Mubarak in 2005 and spent the next four years in jail on trumped-up charges, has invited ElBaradei to quit standing outside the ring like a boxing promoter and get inside the ropes with people who take punches.

Amid so many uncertainties, other Egyptians are just hoping that the octogenarian Mubarak, the pharaoh they know, can hold on a while longer. "I like Mubarak and hope he runs again," said the taxi driver as we pulled to a stop near a red light. He nodded to the policeman.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.