A new documentary called Downwind shines a spotlight on the legacy of nuclear testing in the Nevada desert in the 50s and 60s and shares the stories of those whose lives were the most severely impacted.

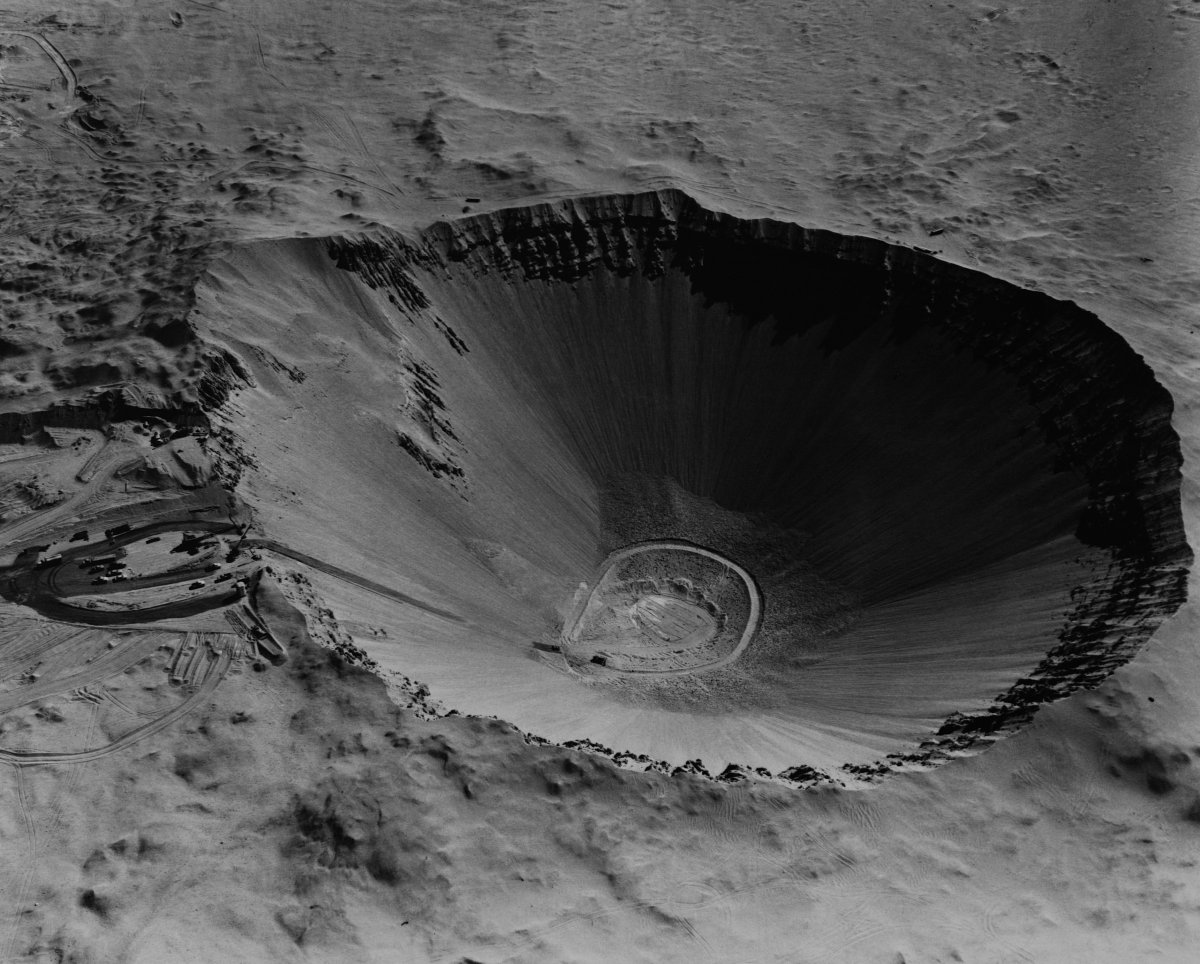

Between 1951 and 1962, nuclear weapons were tested above ground at the Nevada Test Site, based in the Nevada desert, 65 miles north of Las Vegas. Some "928 large-scale nuclear weapons tests [took place] on American soil," Mark Shapiro, who co-directed the documentary with Douglas Brian Miller, told Newsweek. "That sentence on its own is astonishing.

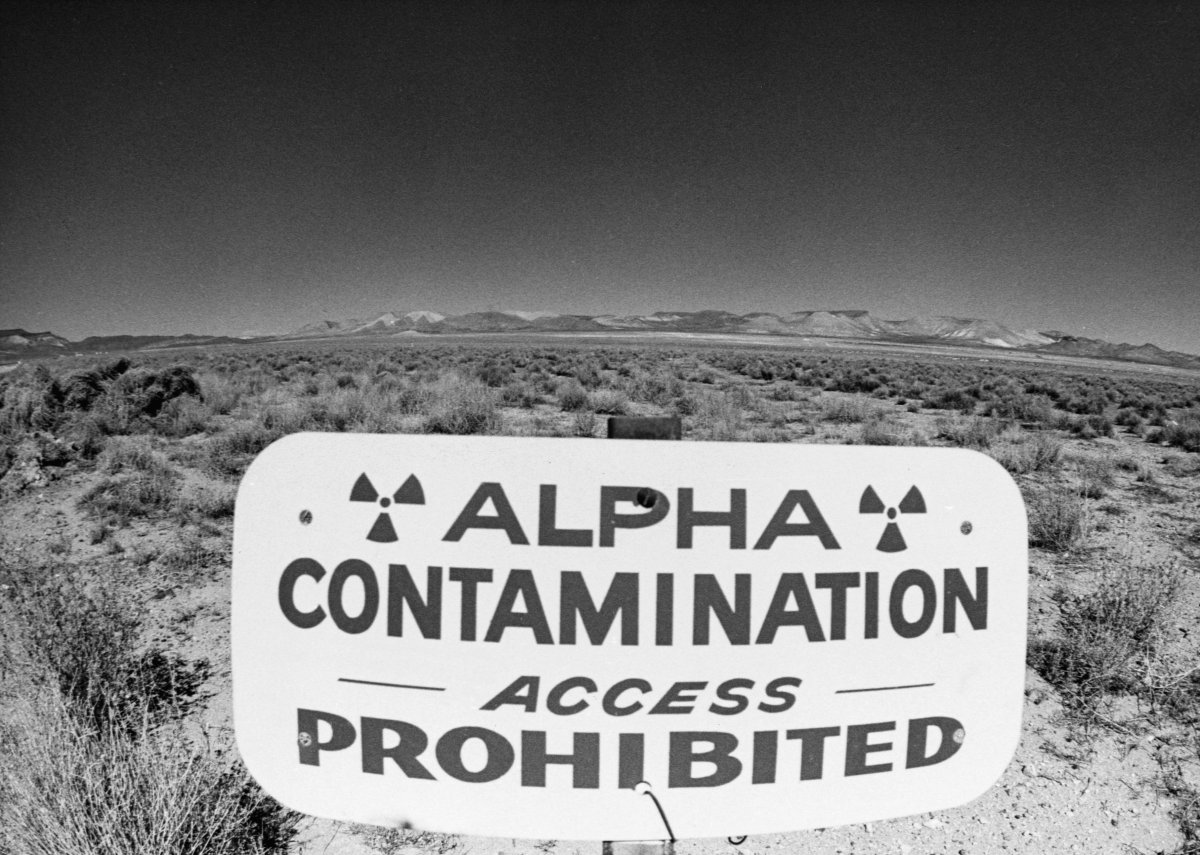

"We wanted to understand exactly who was impacted by the detonations at the Nevada Test Site, since winds dispersed radioactive fallout from atmospheric blasts and underground testing in a seemingly unpredictable manner."

Ken Smith, distinguished professor of family studies and population science at the University of Utah and investigator at the Huntsman Cancer Institute, told Newsweek that the people who were most affected by these detonations, known as "downwinders," were mostly based in Utah, southern Nevada and northern Arizona. "The number of people in that area at the time—[in] the mid-50s to the early 60s—is the concern," he said.

The testing released plumes of radioactive material into the atmosphere, which was carried hundreds of miles by the wind before falling back down to the ground. This "nuclear fallout" material takes many different forms, but one of the most concerning is iodine-131, which can increase risk of thyroid cancer.

It is impossible to accurately determine the dose of radiation and the resulting risk of this exposure, but a report in 1999 by the National Cancer Institute estimated that nuclear weapons testing at the Nevada site would have yielded between 11,300 to 212,000 excess cases of thyroid cancer over this period.

Exposure to radioactive material is mainly thought to have occurred through the consumption of contaminated milk: when iodine-131 falls down to the earth it can settle on vegetation, which is eaten by cows and goats. Over time, the iodine-131 builds up in the animal's bodies and accumulates in their milk, which is then consumed by people. Fresh produce and meat may have also contained small amounts of this radioactive material too, but it would have been less concentrated.

Overall, these concentrations are still very small, but some people would have been more vulnerable to this radiation than others. "It's the children who were the most affected," Smith said. "This is because they drink more milk and have smaller bodies. Your thyroid accumulates iodine-131, and they have a smaller thyroid."

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says that iodine-131 is not the only radioactive material in fallout that affects a person's health. For example, strontium-90 can affect the bone marrow and lead to an increased risk of leukemia.

In Downwind, Miller and Shapiro, spoke to people from Utah and Nevada about how this testing had impacted their communities.

One of the people they spoke to in the documentary was Ian Zabarte, Principal Man of the Western Bands of the Shoshone Nation, whose ancestral lands lie across the Nevada Test Site.

"Nuclear weapons of mass destruction have killed my family, my Shoshone people," Zabarte told Newsweek. "The U.S. secretly occupied Shoshone treaty land then tested 928 nuclear weapons of mass destruction.

"Downwind focuses light on the 45-year gap where the nuclear propaganda glamorized the bright future, over which time we exposed millions of Americans to radioactive fallout downwind and beyond."

Downwind also looks at the story of Mary Dickson, a writer, playwright and downwinder who grew up in Salt Lake City during this period. She ate locally grown vegetables and drank locally produced milk, never knowing the risks of her exposure. At age 29, she was diagnosed with thyroid cancer.

Dickson survived the disease, but others she knew were less lucky.

In a post for the anti-nuclear campaign group, #stillhere, Dickson said that two of her fellow classmates had died of cancer at 8 and 4 years old, and her own sister is now battling a rare form of stomach cancer.

"Sometimes I feel like I am forever piling up losses," she said.

On July 10, 2000, Congress established the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) which provides monetary compensation for the people who developed cancer in light of this exposure. It was due to expire in 2022 but has been extended for another two years.

To date, RECA has awarded nearly $2.6 billion in benefits to close to 40,000 claimants, as per statistics from the U.S. Department of Justice. However, over 13,000 claims have been rejected, and downwinders can only claim compensation if they lived in Utah, Nevada or Arizona during the period of above-ground testing.

Downwind premiered at the Slamdance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, at the end of January. "After our premiere [...] we had folks coming up to us on Main Street with tears in their eyes, thanking us for the story," Shapiro said.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about downwinders? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Update 02/16/23 10:20 a.m. ET: This article was updated to include comments from co-director Mark Shapiro and Ian Zabarte, Principal Man of the Western Bands of the Shoshone Nation.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Pandora Dewan is a Senior Science Reporter at Newsweek based in London, UK. Her focus is reporting on science, health ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.