In the days after New Year's, a senior White House staffer and a campaign aide told Newsweek, the people around Donald Trump were just hoping to get through the final two weeks of Trump's term without a major incident. "Hoping" was about all they could do, said the aide, since "there has never been anyone who can control Trump."

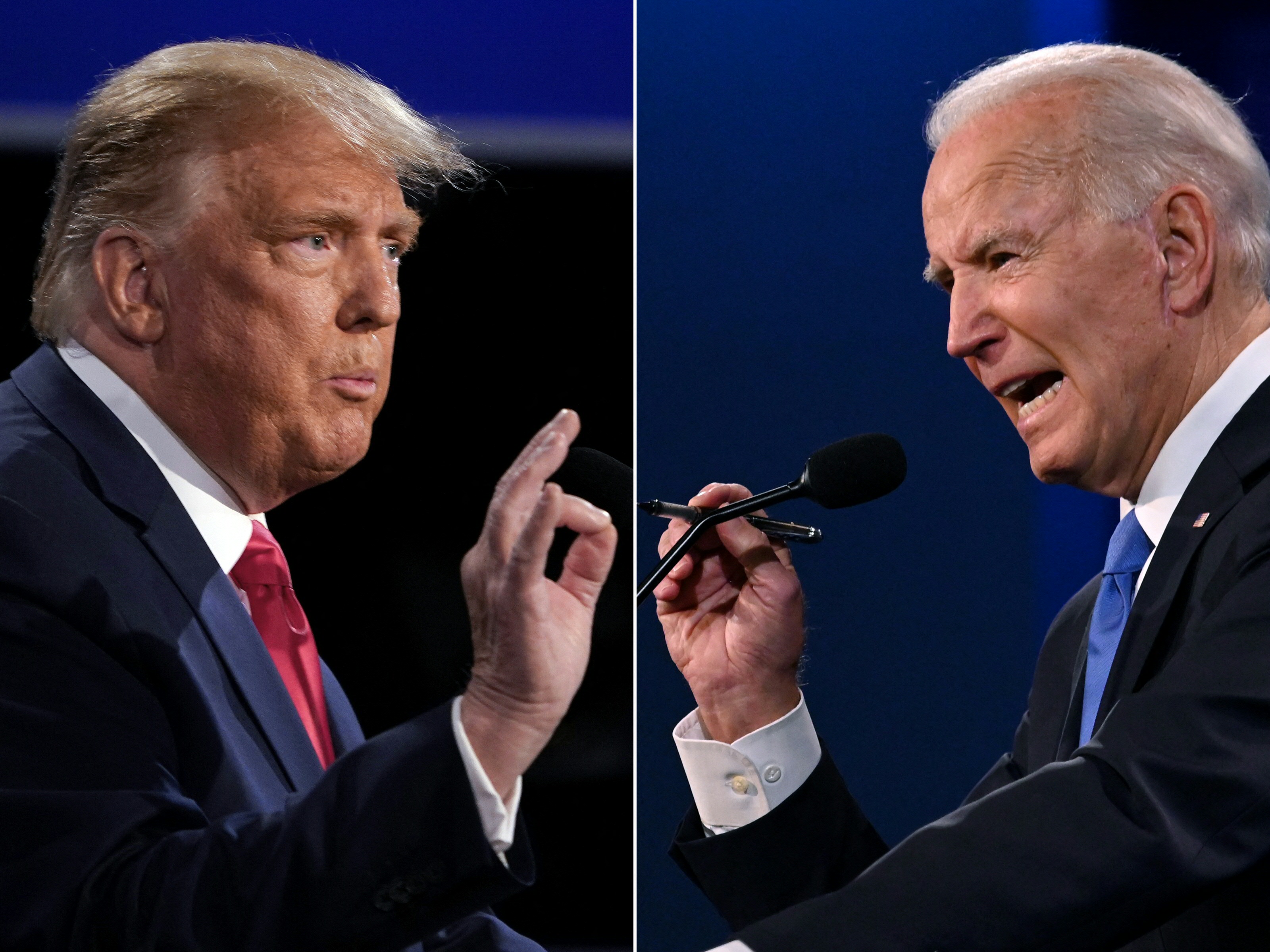

By the evening of January 6, after an angry mob of Trump supporters had ransacked the Capitol building, those hopes were in tatters. Since the November election, Trump had taken his bitterness over the outcome and, with the help of close aides and advisors, channeled it into a campaign to delegitimize Joe Biden and set up another run for the presidency in 2024. In the process, he fueled the belief among his supporters that the outcome of the election could be overturned. On January 6, reality intruded, and that hope turned into rage. And when it did, Donald Trump's hopes for a comeback died.

For months before the election, Trump had tweeted his concerns about mail-in ballots, viewing them as invitations to widespread voter fraud. When he woke up on November 4 to find that his lead the previous night in key battleground states had evaporated thanks in large part to mail in ballots, Trump concluded that he'd been "screwed," as he told a friend later. (Newsweek spoke to more than a half-dozen White House staffers, campaign aides and Trump family friends for this story. They were granted anonymity in order to speak candidly.)

That conviction spurred a chaotic, scatter shot effort to try to challenge the results in multiple states, one marked by disarray and dysfunction among an ever-changing cast of legal advisers, only some of whom had expertise in election law. The president was encouraged by a variety of insiders and outsiders to fight against the election result. One influential voice was that of John Eastman, a professor of constitutional law at Chapman University who had come to Trump's attention by writing a Newsweek opinion piece that questioned whether Kamala Harris was eligible to be vice president—an analysis that was widely rejected.

Others in the circle included Trump's son Don Jr. (described by one White House aide as "more pugnacious" than his siblings); White House aide Stephen Miller; personal attorney Rudy Giuliani; campaign aides Jason Miller and Steve Cortes; former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn; former White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon and conservative chat show host Mark Levin. Bannon and Levin used their popular radio and podcast platforms to incessantly push the claims of fraud.

The White House insiders and family friends say daughter Ivanka and son-in-law Jared Kushner, among others, were more wary of the fight about voter fraud. They wanted the president to commit publicly to a smooth transition of power should his legal challenges fail. Says a friend of the couple: "They weren't telling him not to do what he was doing—they wouldn't do that—but both were concerned that the president's standing would be hurt if he didn't stand down when the time came. As far as I'm aware he told them that he would, and that was the end of it. I think they had maybe two conversations with him about it, and that's it."

Trump is said to have reassured them early on that he would leave office peaceably. He stated so publicly to reporters on November 25, when asked if he would leave office if the electoral college vote was certified. "Of course I will, you already knew that." But then he couldn't help adding, "But I think a lot of things will happen between now and January 20. A lot of things," he said. "Massive fraud detected. We look like a third world country."

By then his pursuit of that alleged fraud was already a mess. Trump had brought in attorney Sidney Powell, who had come to his attention through her representation of Flynn in his effort to get the Justice Department to drop the case against him for making false statements to the FBI. (He had pled guilty; Trump subsequently pardoned him.) Flynn arranged a meeting for Powell at the White House, and by mid-November, standing next to Rudy Giuliani and campaign attorney Jenna Ellis, she was spinning out a variety of conspiracy theories about the election, including one about Venezuelan influence over the voting machine company Dominion Voting Systems.

Her performance was so unhinged that White House Counsel Pat Cipollone, whom Trump trusts, told him she shouldn't be speaking on behalf of the campaign. Members of the president's family were also taken aback, says the White House official. "They thought she came across as a wack job." Trump reluctantly agreed, and on November 22, Giuliani and campaign attorney Jenna Ellis put out a statement saying "Sidney Powell is practicing law on her own. She is not a member of the Trump Legal Team. She is also not a lawyer for the president in his personal capacity."

But Trump was transfixed by the belief that the election had been stolen. Giuliani and Ellis had begun a scramble in key swing states seeking evidence of voter fraud. The president liked Eastman's appearances on Fox News and Newsmax TV, where he promoted the notion that in several states, the electors put forth were not constitutionally valid because local courts had changed a variety of rules regarding mail in ballots—for example, not requiring signatures to be matched to those on voter registration files—without the approval of state legislatures. (The Constitution specifically states, in Article II, that "each state shall appoint, in such manner as the legislature thereof may direct, a number of electors, equal to the whole number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress.") In Pennsylvania, Georgia and Arizona, Eastman would argue, the legislature's role had been usurped by either courts or secretaries of state, thus making the electoral votes submitted from those states unconstitutional. Talk show host Levin made this argument night after night starting in late November, and it would become central to Trump's hope that Pence might send some of the electors back to the states on January 6.

Whatever the merits of that case, White House officials, including Cipollone and others in the office of legal counsel, thought the legal strategy was half-baked. The White House joined a case filed by the state of Texas—with Eastman as the lawyer of record—seeking to overturn the results in Michigan, Pennsylvania and elsewhere based on this notion. It wanted the Supreme Court to hear it. But it was obvious the state of Texas had no standing to challenge electors in other states. "There was never a chance the court would hear that case, it was preposterous on its face," says a recently departed member of the office of legal counsel. "It really made it seem that the campaign, and those representing it, had no idea what they were doing."

While the legal strategy stumbled, political operatives around Trump—and the president himself—came to the realization in late November that what one aide called the "we was robbed" theme was politically useful. This included Don Jr., multiple sources say, who always understood that the Trump political brand came down to one word: fight.

"There was no 'aha' moment, when someone sitting around a table said, 'you know, this might work setting the table for a 2024 run,'" says one of the White House staffers. But it became apparent by early December that the idea of a stolen election had gained traction. Despite the mainstream media consistently calling the claim "baseless," some 77 percent of Republicans by late December believed Trump was right, that the election had been "rigged." So Trump would fight to the bitter end.

Trump loved the idea: delegitimize Biden from the outset by contesting the result of the election, and begin to plan for a 2024 rematch. That's why, at a White House Christmas party on December 3, he told supporters, "We are trying to do another four years. Otherwise, I'll see you in four years." The crowd whooped and cheered in response.

By the end of December, in the eyes of Team Trump, the political strategy was working. Trump's base was solid in support of his contesting the election. But the legal effort was flailing. None of the cases Trump and his allies brought around the country amounted to anything, though as Eastman pointed out, the vast majority of those were dismissed on procedural grounds not on the merits. On December 18, Flynn had brought Powell back to the White House for yet another meeting. This time, Trump was considering appointing her as special counsel in order to investigate election fraud. Cipollone and Meadows attended the meeting as well, and were strongly opposed to the idea. Giuliani, piped in over the phone, also objected. And though they were not present, Ivanka and Jared Kushner also were appalled at the idea, says a friend of the couple. The meeting devolved into a shouting match, according to multiple sources. Powell urged Trump not to "quit" fighting to overturn the election results. But in the end, Trump relented and dropped the idea.

The family retreated to Mar-a-Lago for Christmas, but the fight over election fraud was uppermost in Trump's mind. One of his favorite occasions each year is a New Year's Eve party he hosts at the resort for his friends. This year he blew it off, returning to Washington on December 31. In part, say one White House official and one senior campaign aide, that was because he wanted to be seen as pushing for a $2,000 per person Covid-19 relief check. "But mostly he wanted to put some heat on congressmen and senators about the sixth," says the campaign staffer.

"The sixth" was a reference to Congress's gathering to certify the count of electoral votes—the last step in the process of affirming Joe Biden's victory. Eastman, according to multiple sources both inside and outside the administration, had convinced Trump that Vice President Pence had the authority to send the votes back to state legislatures in states like Pennsylvania. Steve Bannon kept saying on his daily podcast, War Room Pandemic, that Giuliani and the other lawyers "had the receipts" proving voter fraud, and that Pence needed to stand up and "do the right thing." Campaigning for Republican Senate candidates in Georgia on January 4th, Trump issued a veiled threat to Pence, saying if the vice president didn't act, "I won't like him quite as much." This, aides say, was Trump acting from what he perceived to be his position of strength. He would be the front runner in 2024, and even if he decided not to run, he would be the most powerful force in the party, able to determine who his successor would be. No one, after all, could draw a crowd like him.

That was clear enough on January 6, a cold sunny morning in Washington, when tens of thousands showed up for the "stop the steal" rally. In a matter of hours, after directing his followers to march to the Capitol to "peacefully and patriotically" protest in hope of persuading Congress not to ratify Biden's victory, Trump would be in the White House, watching the television images of the Capitol being stormed. Pence would have to be hustled out to protect his safety.

The events, for Trump, his family and his loyal aides, were catastrophic. The rally was all about Trump's political future; it was him fighting to the end, as his brand required. But by the end of the day, that political future no longer existed. Of the family's friends, says one, "only the most sycophantic still resisted the notion of what an absolute disaster this was."

For the Trump clan there was a personal cost as well. Jared Kushner's sister-in-law, supermodel Karlie Kloss, called out the president on Twitter: "accepting the results of a democratic election is patriotic. Refusing to do so and inciting violence is anti-American." When a respondent asked, why don't you tell your brother- and sister-in-law, she tweeted, "I've tried." Kushner and Ivanka were said to be angered by the public exchange. In Trumpworld, loyalty comes first. But they also knew that many in their social circle felt the same way Kloss did. "They know they've got work to do to repair relationships," is how one New York friend of theirs put it. "They're not idiots."

A week after the Capitol riot, the House was impeaching Trump for a second time and Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell, with whom the president had worked closely for four years, had let it be known that he thought Trump had committed an impeachable offense. A dispirited Trump aide, who had been with him from the beginning, said: "For a time, even though we knew we weren't going to overturn the election results, we still thought we were winning. We were winning. And then, all hell broke loose."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.