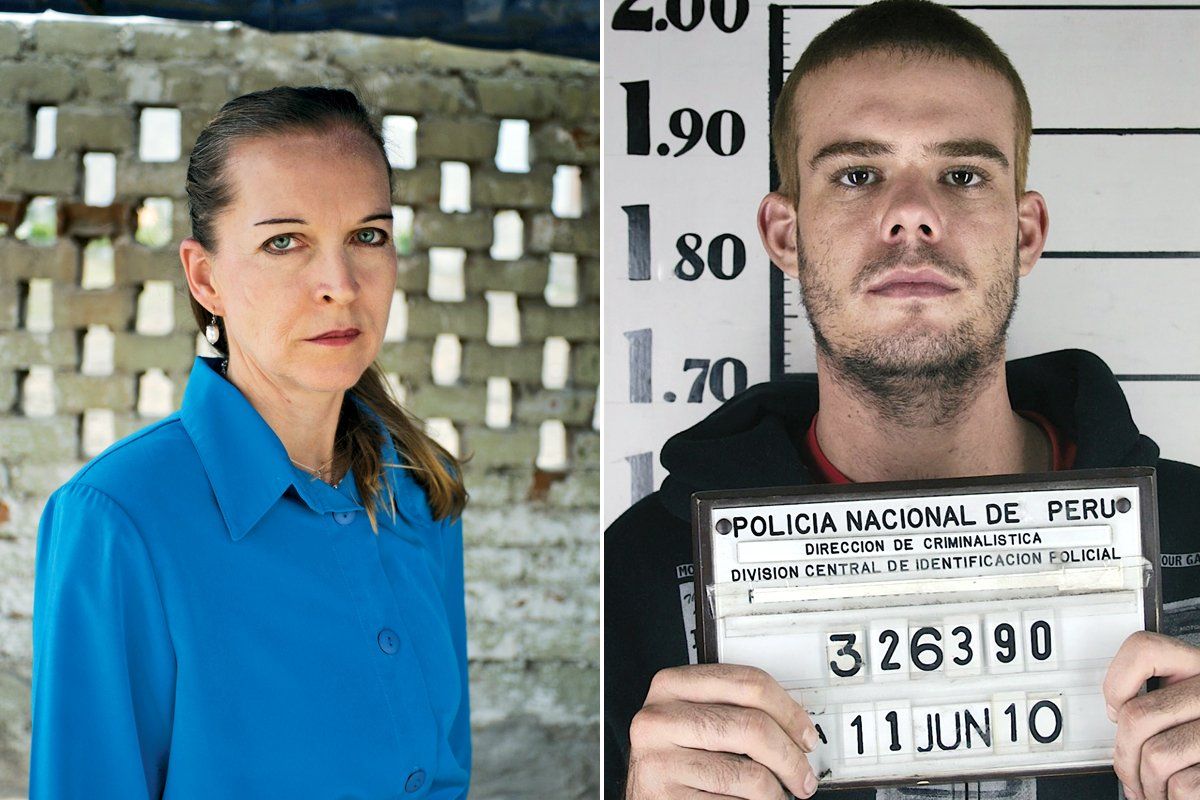

Dr. Mary Hamer, 55, dresses very carefully before she visits the prison. The young man she goes to see in the forbidding complex, where rats crawl out of the drains and the dust of the nearby desert settles on everything, is someone she's come to think of as a possible spiritual leader, maybe Gandhi, and she wants to make a good impression. If only he could spend a decade or so under her wing, she believes, he could realize his full potential. Already Hamer, a divorced radiologist from Lake City, Fla., is doling out her savings to pay his lawyers. She is buying him clothes. She is sending him care packages. If only he were released into her custody, she would cast out the violence like a gentle exorcist coaxing away the demons. And if he has murdered before, he would murder no more.

Hamer has styled herself the young man's guardian angel, but she could just as easily be his latest victim.

Probably you have heard the young man's name: Joran Van der Sloot. The 24-year-old Dutchman has been linked again and again to the disappearance of Alabama high-school senior Natalee Holloway, a pretty, blonde cheerleader who went missing when she accompanied her class to the Dutch island of Aruba in the Caribbean for a postgraduation blowout in 2005. Her body has never been found. The body of another young woman linked to van der Sloot was discovered, however, decaying beside his bed in the cheap hotel room in Lima he had taken in May 2010. Peruvian Stephany Flores, 21, had been savagely beaten. Van der Sloot was arrested in Chile days later and shipped quickly back to Peru, where his trial is due to begin Jan. 6. If convicted of killing Flores, he could spend 30 years in the harsh Peruvian prison system. But even now, from behind bars, he has proved strangely, frighteningly attractive. One woman in particular has been pulled into his orbit and seems to be suffering the consequences, even if it's not her life that's in danger. Hamer, apparently entranced by the young man suspected of killing two young women, has devoted her money, her adoration, and her time to him.

Van der Sloot was born in the Netherlands but raised in Aruba, growing up in a vacation paradise where easy hedonism was on offer just about everywhere you looked. When Van der Sloot met Natalee Holloway in the Holiday Inn casino in Aruba on the night of May 29, 2005, she was 18 and he was only 17. At the end of the evening, Holloway, a straight-A student with a high-school résumé full of charity work and Bible study, wound up at a bar talking to the 6-foot-4 Van der Sloot. She has not been seen since.

In 2008 Van der Sloot was recorded by hidden cameras while riding in a car with a buddy who'd sold him out to Dutch TV, and he half-explained what might have happened. He claimed that Holloway and he had gone to the beach and that she was very drunk and had some kind of seizure. He said he panicked and decided to dump the body at sea.

The tape, watched by millions of people around the world, still didn't send Van der Sloot to jail. Without a body there was no case. But the video made Van der Sloot an international pariah.

Van der Sloot didn't exactly lay low. In 2010 he allegedly tried to squeeze $250,000 out of Beth Holloway, Natalee's mother. In return, he promised to reveal "the location of Natalee Holloway's remains in Aruba and information regarding the circumstances of her death," according to a criminal complaint filed later that year. Beth Holloway tipped off the FBI. She also gave Van der Sloot a down payment of $25,000.

He took the money and ran. From Aruba Van der Sloot headed to Lima, where a big poker tournament was coming up in early June. Playing in games before the tournament, Van der Sloot lost. He allegedly then set his sights on Stephany Flores. They had a mutual acquaintance at the casinos. She was from a relatively well-to-do Lima family, and rumor had it she'd made some recent big scores gambling.

He and Flores arranged to spend the predawn hours of May 30, 2010, together at the tables. At about 5:30 a.m., Van der Sloot persuaded Flores to go back to his hotel with him to keep gaming on his laptop. As they started to play, an email or Facebook message popped up on Van der Sloot's screen: "I am going to kill you, mongolito [little mongoloid]," it read. Who sent it remains unclear, but May 30 happened to be the fifth anniversary of Holloway's disappearance.

Van der Sloot, by his own account, told Flores some of the story. According to the confession he gave Peruvian police (and later recanted), Flores hit him. He swung his elbow around and smashed her nose, which started gushing blood. Then, he said, he just lost control, smothering her with a bloody shirt and throttling her. He took all the money she had on her, he said, about $300.

Van der Sloot fled for Chile. Soon after he got there his picture appeared all over the front pages. The Chilean police arrested him and turned him over to the Peruvian police. They took him to the overcrowded Miguel Castro Castro Prison on the outskirts of Peru's capital. At last, it seemed, this alleged killer was finally in a place where he could no longer hurt women. But his lure remained strong.

In the early days of his detention, the Lima papers were full of reports about him reading reams of letters from women who claimed to be in love with him. "I get more letters every day," he bragged to the downmarket Dutch paper De Telegraaf. "One of them even wanted me to get her pregnant."

His spell reached all the way to Florida.

The first time Mary Hamer saw Van der Sloot on television and the Internet after his arrest in Peru, she instantly felt a need to reach out to him, to help him, to stand by him. At her radiology practice in Lake City she sees a lot of veterans. (She didn't want to give the precise name of the hospital.) She's trained to spot signs of posttraumatic stress disorder, she said, and claims she could see just from the pictures in the news that Van der Sloot was suffering from PTSD. The media and the lawyers, she concluded, had broken him down after the Holloway case.

Of all the women who reached out to Van der Sloot, Hamer was the one who got through to him in person. First she contacted the high-profile American attorney who had helped Van der Sloot in Aruba. Eventually, she says, he put her in touch with Van der Sloot's mother, Anita Van der Sloot, who was living in Holland. The two women got along well long distance. (Despite repeated email requests, Anita van der Sloot declined to speak with us for this story.)

At first Hamer sent care packages to Van der Sloot for his birthday in August 2010: tomes on how to quit smoking and gambling; self-help books by Wayne Dyer and Deepak Chopra; works on Gandhi and Mother Teresa. "I love sending him packages," she says. She kept thinking of things he might need, even if he didn't ask for them. For his hygiene she sent him "boatloads of Germ-X and boatloads of lemon wipes," she says. She bought him a shirt to wear in court, and pants: "You can't find 34–36 most places, but I keep trying."

Then, in December 2010, having won approval from his mother and his lawyers, Hamer made her first of three trips so far to Peru to see Van der Sloot in person. Her third visit was this month. "Since I don't have children, I have all this extra free time," says Hamer, who has devoted herself to many causes, from saving wild mustangs to the people of Gaza. "I have a very strong feeling about protecting. It's a very deep natural instinct of mine that is driving me—not driving me, but allowing me the freedom—to help Joran."

Hamer is wary of any suggestion that there is sexual attraction in this relationship. She doesn't even like to describe Van der Sloot as a friend, which "has many meanings." She refers to herself as his "spiritual guide," or "mentor." "Everybody in life needs one mentor," she told a reporter one recent morning before heading to the prison. "A person who believes in you and loves you—agape love, spiritual love—not sexual love. Be careful! Spiritual love." She thinks that feeling is reciprocated by Van der Sloot. "He's not manipulating people, he's genuine," she insists.

When Hamer came out of the prison, she seemed almost inspired. Van der Sloot had told her that making peace with Ricardo Flores, Stephany's father, "is much more important than the trial." He told her, "I've learned from you that revenge is not the way." Hamer vowed on the dusty road leaving the prison that she would never let Van der Sloot down: "I come every six months. I will come for the rest of my life. I have even told Joran I will move here. I will tell them [the authorities] I will move into that prison and live with him, because I am committed."

But even during that visit there were signs of trouble. She was not allowed to go to Van der Sloot's cell as she had done on previous trips. That frustrated her. Among other things, she wanted to play him a CD of her own songs that she had written and recorded. She wanted to get his reaction to "Rescue," which she wrote for him, and to such titles as, "Come Ride With Me," "Haven't Kissed You Yet," "Zen Calm," "Caretaker," and "Gandhi."

Hamer and Van der Sloot had to meet in the prison cafeteria. As they talked she wrote down what he said. Soon the prison authorities called him into their offices for a reprimand. Reporters are not allowed to talk to Van der Sloot, and they were suspicious. When he came back, as Hamer tells the story, there was an emotional scene. "Joran was shaking, scared, nervous," she said.

That same day children with their grandfather visiting another inmate started playing around with van der Sloot, trying to take his chair from him. Everyone was laughing. Then Van der Sloot walked away to talk with the grandfather. Hamer didn't hear that conversation, but when Van der Sloot came back he said, "Mary, guess what? They named their newborn grandson Joran." Hamer was thrilled as she told the story. It didn't occur to her that Van der Sloot might have made it up. It was so much the kind of thing she wanted to hear. "When people know Joran," she said, "he's lovable."

Toward the end of that afternoon, Hamer noticed what looked like a recent scar on van der Sloot's upper lip. She reached out and touched it. "What happened?" He said someone had hit him in the back of the head and slammed down his face, driving a tooth through his lip. Hamer asked if his attacker was a guard or another prisoner. "He didn't answer and he started shaking," she said. Later Hamer retracted her suspicions, saying she believed the scar is visible in a June 2010 photograph of Van der Sloot.

Hamer, it would seem, is hooked. And the experience of trying to look after Van der Sloot was clearly taking its toll on her. Each subsequent day became more difficult—a protracted set of petty negotiations that ended again and again in failure to see the man she so wanted to protect.

Under the hot sun outside the prison, Hamer started airing in public her unproven theories about conspiracies against Van der Sloot. She started talking to television cameras—which made the authorities even more suspicious that she might be a journalist. She denounced Peruvian government officials, including the ex-president. She shared her suspicion that the prison doctor was giving Van der Sloot dangerous drugs, and word got back to the prison administration. Van der Sloot's lawyer was then notified that Van der Sloot had been taken to the prison hospital to be monitored for the drugs that Hamer had accused the prison doctor of administering. Hamer looked under great strain, and she appeared to be reaching the end of her usefulness to van der Sloot.

And so finally Van der Sloot delivered a painful blow. He rejected her. Through a third party, Van der Sloot sent word to his attorney: please get Hamer to back off.

On Wednesday afternoon, the day she had booked herself to leave Peru, Hamer sent a text message to a reporter to say she wasn't being let inside again because "I'm talking to the media." She said her freedom of speech was being limited. She said Van der Sloot was being punished. She was going to up her demands for a lawsuit against the U.S. Justice Department, which had not answered her questions about an FBI plot she believes targeted van der Sloot. But she was committed to Van der Sloot, she said. She would stay with him as long as he wanted her to.

That evening Hamer went back to Florida.

Additional reporting by Barbie Latza Nadeau, Jessica Bennett, and Nadette de Visser.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.