People remember where they were when important things take place. You remember where you were when Kennedy was shot or when men landed on the moon or where you were (and probably what you were wearing) when your husband proposed. Me, I remember where I was sitting the first time I saw Bonnie and Clyde.

It was the first matinee show on a Saturday at the Carolina Theater in Winston-Salem, N.C. My recollection is precise because Saturday mornings at that theater were devoted to what was called the Kiddie Show. Local disc jockeys hosted a morning's worth of entertainment that included cartoons, serials, and maybe a Hercules movie. The audience spent most of its time throwing popcorn or pouring drinks from the balcony onto saps in the orchestra seats.

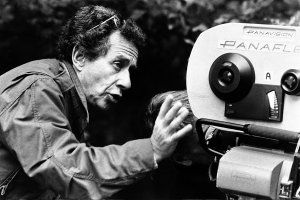

In the late 60s, movie-theater owners had not begun the practice of clearing the theater after every show, so the first Saturday matinee always had a few children left over from the Kiddie Show. So there I sat that Saturday, all of 16 but still the oldest person in the nearly deserted auditorium. I was there because I'd read a couple of rave reviews about a gangster movie starring two people I'd never heard of, written by people I'd never heard of, and directed by Arthur Penn. Him I knew about. He'd directed The Miracle Worker. I'd seen it on the late show. The other kids were there because they had nowhere else to be. None of us knew what was about to hit us.

I don't remember exactly when the first kid started screaming. For the first 20 minutes or so, they'd been laughing at the movie when they weren't ignoring it outright. They even laughed at some of the violence, although nothing too awful happens right away in that movie. I'd guess it was somewhere after the first big bank robbery, since that's the moment when I sat up and started paying attention. The bank robbery is more or less like any movie bank robbery until Bonnie and Clyde jump in the getaway car. As C. W. Moss drives them away, a bank official jumps on the running board and clings to the outside of the car. Clyde shoots him square in the face, and he falls out of sight. Someone in the audience laughed but it sounded almost like a scream, and after that things got pretty quiet in the theater. After the scene where the police corner the Barrow gang in a house and Clyde's brother and sister-in-law get shot up, I looked around and saw that most of the kids had left. By the time the movie ended, I had the place almost to myself.

Here's the thing: I didn't feel a bit superior to those little kids. Bonnie and Clyde scared me as much as it scared them. More precisely, it unsettled me. The people in the movie were likable one moment and loathsome the next. The tone was lighthearted, then pitch-dark. You didn't know when you were supposed to laugh, or when something funny was about to turn murderous. At 16, I had seen a lot of movies, but all the movies I knew about—Hollywood movies—telegraphed their punches in an almost ritual way. Since I had at that point never seen—or even heard of—any films made by the French New Wave directors, I didn't know that Arthur Penn and his scriptwriters, David Newman and Robert Benton, were tipping their hats to Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut (who'd been offered the job of directing Bonnie and Clyde and declined). I didn't know that for most of the past decade the French had been pioneering this intoxicating blend of improvisation, tragicomedy, and characters who charm and repel in equal measure. I didn't know that Bonnie and Clyde was Hollywood's bid to catch up with one swoop. But catch up this movie did, opening the door for Peckinpah, Altman, Bogdanovich, Scorsese, Coppola, and all the other young filmmakers who would turn the 1970s into one of the golden ages of American filmmaking.

Arthur Penn, who died Sept. 28, the day after his 88th birthday, made some good movies in his life (Night Moves, The Miracle Worker) and succeeded almost every time he directed a Broadway play (the younger brother of the great photographer Irving Penn, Arthur attended the experimental Black Mountain College and began his career in theater and the improvisational world of early television drama). But he never made anything as good as Bonnie and Clyde. It was an act you couldn't top, and I'm not sure I'd want to see anything that could. Much of what's good about the movie is in the screenplay, but Benton and Newman, together or singly, never did better. Neither Faye Dunaway nor Warren Beatty ever turned in a better performance (Gene Hackman and Estelle Parsons were just their usual excellent selves).

But what makes the move work is the blend of all these things. It's the acting. It's the story. It's the music (the Flatt & Scruggs soundtrack—thrilling and corny and apt—and again, is this a joke, is this real, what's going on here?). It's the photography (has a movie ever managed to look so simultaneously precise and dreamlike?). It's none of these things taken separately but all together, or, to quote a Faye Dunaway character from another movie, "My daughter, my sister, my daughter, my sister." Together, these elements gel into a startlingly original movie, and because these things never happen by chance, we have to credit Arthur Penn. Is one great movie enough to say a man is a great director? Yes indeed, if the movie is Bonnie and Clyde.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.