Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, the most powerful man in Pakistan, gazed across the parade ground of his country's equivalent of West Point. Row upon row of graduating cadets stood at immaculate attention in their green berets and khaki uniforms, their boots covered by pristine white puttees. "The terrorists' backbone has been broken, and God willing, we will soon prevail," the Army chief told the future commanders.

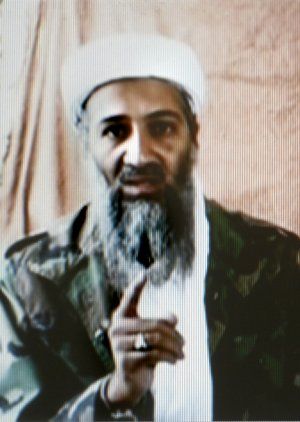

The leaders of the ranks saluted, their drawn swords glistening in the sun. Osama bin Laden may have heard the parade—and maybe even the speech. He was holed up in a three-story villa within a high-walled compound just down the street.

Nine nights later, after midnight on May 2, people in the hill town of Abbottabad heard the muffled flutter of helicopter rotors and the blasts of combat as U.S. Navy SEALs dropped behind those high walls. In less than 40 minutes, bin Laden was dead.

When President Barack Obama announced the kill that night in Washington, America erupted in celebration. "The war on terror is over!" shouted Jake Diliberto, a former Marine and opponent of the ongoing U.S. occupation of Afghanistan, outside the White House. But the elation was almost certainly premature. "It's not over at all," says a senior American intelligence officer who has tracked bin Laden for almost two decades. Few fights have ever been more complex and frustrating than the global campaign to eradicate Al Qaeda. And nothing has made that clearer than the long hunt for bin Laden himself.

That hunt has come to an end, accompanied by a volley of relief and jubilation. Pungent questions remain, however, as does the need for intense national self-criticism: what took us so long? Were we simply unlucky, or were we often ham-handed and overcautious?

After all, U.S. officials became aware of his potential for trouble in the early 1990s. He had been active in the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan, but after the Russians pulled out in 1989, he went looking for new targets. He moved to Sudan and began funding terrorist movements all over the Arab world. Washington pressured Sudanese leader Omar Bashir's regime until bin Laden was expelled in 1996. "We wanted him out of Sudan," says the senior officer, who dealt with the case and whose current position does not allow him to speak on the record. "The question was where would he go, and who would take him."

Bin Laden ended up back in Afghanistan, where he quickly allied himself with Mullah Mohammed Omar, whose Taliban fighters were in the process of gaining control over the war-torn country. "We should have left him in Sudan," says the officer. "Bashir you could work with. Mullah Omar you couldn't." Now bin Laden had a new sanctuary—and big plans for how to use it. He issued what he called a "declaration of war" against the West, and when few people took notice, he issued what he called a fatwa—a religious edict—approving the killing of "crusaders," meaning Americans and Jews, anywhere in the world. He joined forces with an Egyptian terrorist leader named Ayman al-Zawahiri, and Al Qaeda as we have come to know it was born.

The CIA saw what was happening, but it was painfully short on money and personnel. The agency had suffered one scandal after another. It had been penetrated by Russian agents. Powerful voices on Capitol Hill questioned whether there was still a need for the agency at all. Case officers who manage human sources of intelligence are vital when tracking someone like bin Laden, but in 1996 only six case officers were in training for assignments anywhere in the world. So the agency tried something new—it set up a special CIA station based in Virginia, focusing on just one man: Osama bin Laden. The hunt began in earnest.

Then simultaneous suicide bombings hit American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in August 1998, killing more than 200 people and injuring thousands. In retaliation, President Bill Clinton ordered cruise-missile attacks on targets in Sudan and Afghanistan, including a training camp where it was thought bin Laden might be hit. Nevertheless, he escaped unharmed. Clinton's critics accused the president of trying to divert attention from the Monica Lewinsky scandal.

According to Paul Pillar, who was then at the Counterterrorism Center, a plan was drawn up to capture bin Laden. But senior administration officials including George Tenet, the CIA director at the time, refused to sign off on it. "It came to the point of being all set, ready to go, coming down to the final decision of do we take a chance on this," says Pillar, "and the final decision was no." The plan relied on local agents, not U.S. operatives, and the risk of failure seemed too high.

In 2000 another Qaeda attack followed: a suicide bombing in Yemen that killed 17 American personnel aboard the USS Cole. The CIA and FBI pursued leads all over the world, searching for the terrorists responsible, but they missed a group of Qaeda operatives attending flight schools in the United States. And on September 11, 2001, bin Laden struck again.

In a matter of weeks, U.S. forces and their Afghan allies toppled the Taliban government and closed in on bin Laden in the desolate mountains of Tora Bora, near the Pakistan border. But somehow he got away. British Prime Minister Tony Blair, Bush's closest ally, remembers the intense sense of frustration. "The hunt was on, the search was on," he says. "But the weeks turned into months, turned into years. People found it hard to believe that someone could be scrubbed off the face of the world, could simply sink into obscurity."

Where had bin Laden gone? The best guess seemed to be the mountains of Kunar province, in eastern Afghanistan—remote, sparsely populated, lacking good roads, crisscrossed with smugglers' trails, and largely covered with evergreens and shrubs (unlike the more open, largely treeless hills on the Pakistani side of the porous border). "It's impossible to access the areas where Al Qaeda is hiding," Kunar's then chief of police, Col. Abdul Saffa Momand, told NEWSWEEK in 2003. "Even from a helicopter you only see mountains, rocks, and trees."

Khan Kaka, a gray-bearded, almost toothless man living in a mud house with a weather-beaten pine door, told NEWSWEEK in 2003 that his son-in-law, an Algerian, was a senior bodyguard to bin Laden and brought news from the hideout every few months, Asked where bin Laden was right then, Kaka grinned and waved silently toward the 12,000-foot peaks surrounding the valley: up there.

But "up there" may not have been far enough. In late 2004, an Al Qaeda sentry near bin Laden's camp spotted a patrol of U.S. soldiers who appeared to be headed straight for the Qaeda leader's hideout. Word quickly passed among bin Laden's 40-odd bodyguards. As an Egyptian Qaeda operative later recounted, the anxiety level grew so high that the bodyguards prepared to issue the code word to kill bin Laden and commit suicide, in accordance with his decree that he would never be captured. The secret word was never given. As the Qaeda sentry watched, the patrol moved off in a different direction. Bin Laden's men concluded that it was only by accident that the soldiers had nearly stumbled on their hideout. (A former U.S. intelligence officer tells NEWSWEEK he was aware of official reporting on this incident.)

After that close call, bin Laden shrank his security staff and employed only faithful Arabs, according to Omar Farooqi, a Taliban liaison to Al Qaeda. A Western military official who has worked both sides of the Afghan-Pakistani border tells NEWSWEEK that bin Laden may have deployed small groups of decoy bodyguards all along the frontier, each with the same "signature": small security detail, secretive, saying little to local villagers, always moving on. That's a perfect disinformation campaign, says the official. The nearby locals start whispering that bin Laden must be nearby. "Word gets around that it must have been him," he says. "We react. It throws us off the trail and makes us waste assets following bad leads. And it's a cheap and easy way to do it."

In Washington, the frustration was almost palpable. U.S. Navy SEALs and other American Special Operations teams mounted repeated missions into Kunar's rugged mountains, only to come up empty-handed. In June 2005, President Bush approved what was called Operation Redwing. One of those on the mission had worked with Homeland Security adviser Frances Townsend. The aim was to capture a Taliban leader who was supposed to know where bin Laden was hiding. But the operation was compromised during a reconnaissance patrol when they ran across some shepherds. After the Americans let them go, the shepherds told the Taliban, who quickly launched an attack, killing three of the four Americans. Another 16 U.S. Special Ops soldiers, including Lt. Cmdr. Erik Kristensen, the son of an admiral, died when their helicopter was shot down trying to rescue the sole survivor. Townsend says her most intense memory about the event was "writing letters to the families of those who were killed."

In 2006 the Americans thought they had another lead—a grainy photograph of someone who looked like bin Laden, supposedly snapped in the tribal areas of Pakistan. But the Pakistani government made excuses, rather than acting on the lead. In 2007, another tip seemed promising when a previously reliable source claimed to have bin Laden's itinerary. Units were dispatched to intercept him, but came back empty-handed.

By then, U.S. officials now believe, their quarry had moved into the villa in Abbottabad, hiding under the very noses of the Pakistani military. All he had to do was to adopt the lowest profile and rarely if ever leave the house. (When local boys kicked a soccer ball over the wall, they were given money rather than allowed to retrieve it. When local public-health nurses made rounds to check on women, they were always turned away.)

But perhaps most important, bin Laden allowed no phones or Internet connection into the compound. He had learned from bitter experience that the key to survival was to cease all electronic communications. Both his operations chief, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, and KSM's replacement, Abu Faraj al-Libi, were tracked down by U.S. intelligence using sophisticated electronic intercept and eavesdropping equipment. "Every time he named a 'No. 3' who had to communicate with the outside world, that shortened the guy's lifespan," says Townsend, "and bin Laden realized this." But he continued using trusted couriers to hand-deliver messages to and from his lieutenants in the field.

Since the 1990s, American intelligence agencies had known that bin Laden used this method. "The notion that couriers would be the key to finding him was there from the start," says Jane Harman, who sat on the House intelligence committee as the hunt began in earnest after 9/11 and is now on the board of directors of The Newsweek/Daily Beast Company. Not until 2007 did patient investigation and endless interrogations finally yield the identity of bin Laden's most trusted courier, a man who used the nom de guerre Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti. By then, however, the CIA had developed the people it needed for the job of tracing his movements. For years the CIA had been "churning out case officers," says Townsend. Now many of them had the kind of experience needed for the hunt's last phase, which took months of surveillance on the streets, together with satellite photos and electronic monitoring of Abu Ahmed's movements.

As negotiations to free the U.S. intelligence contractor Raymond Davis were wrapping up on March 14, CIA director Leon Panetta presented President Obama with three options for hitting the bin Laden compound: a B-2 stealth-bomber strike that would obliterate it, a U.S. Special Operations attack, or a combined U.S.-Pakistani assault. Obama took the second option. He wanted no questions about whether or not bin Laden was dead, and nobody trusted the Pakistanis not to leak what was being planned, and perhaps even tip off bin Laden.

On Sunday morning, May 1, Obama played nine holes of golf, rather than his usual 18, and headed back to the White House. He and other senior officials, including Vice President Joe Biden, Defense Secretary Robert Gates, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton watched mesmerized, and sometimes horrified, as video cameras with the special forces relayed the action back to Washington. Panetta watched from CIA headquarters at Langley, Va. The SEALs searched the house floor by floor, room by room. As they climbed to the top floor, bin Laden's son came onto the stairs, brandishing a weapon. They took him down. As they entered the bedroom, bin Laden's wife rushed at them. She was shot in the leg. And then there was the man himself, unarmed and dressed in a loose-fitting shalwar kameez.

"Geronimo," one of the SEALs reported, using the code name given the world's most wanted terrorist. Bin Laden took a bullet to the chest. Then another to the head. "Geronimo EKIA," came the report heard at Langley and the White House. Enemy killed in action.

U.S. helicopters picked up the SEALs and bin Laden's corpse. It was 1:15 in the morning of May 2 in Pakistan. The choppers flew to Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan, where the body was identified conclusively. A few hours later he was buried at sea. No shrine will ever mark his tomb.

The hunt was over.

With John Barry, Mike Giglio, R. M. Schneiderman, and Nazar Ul Islam

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.