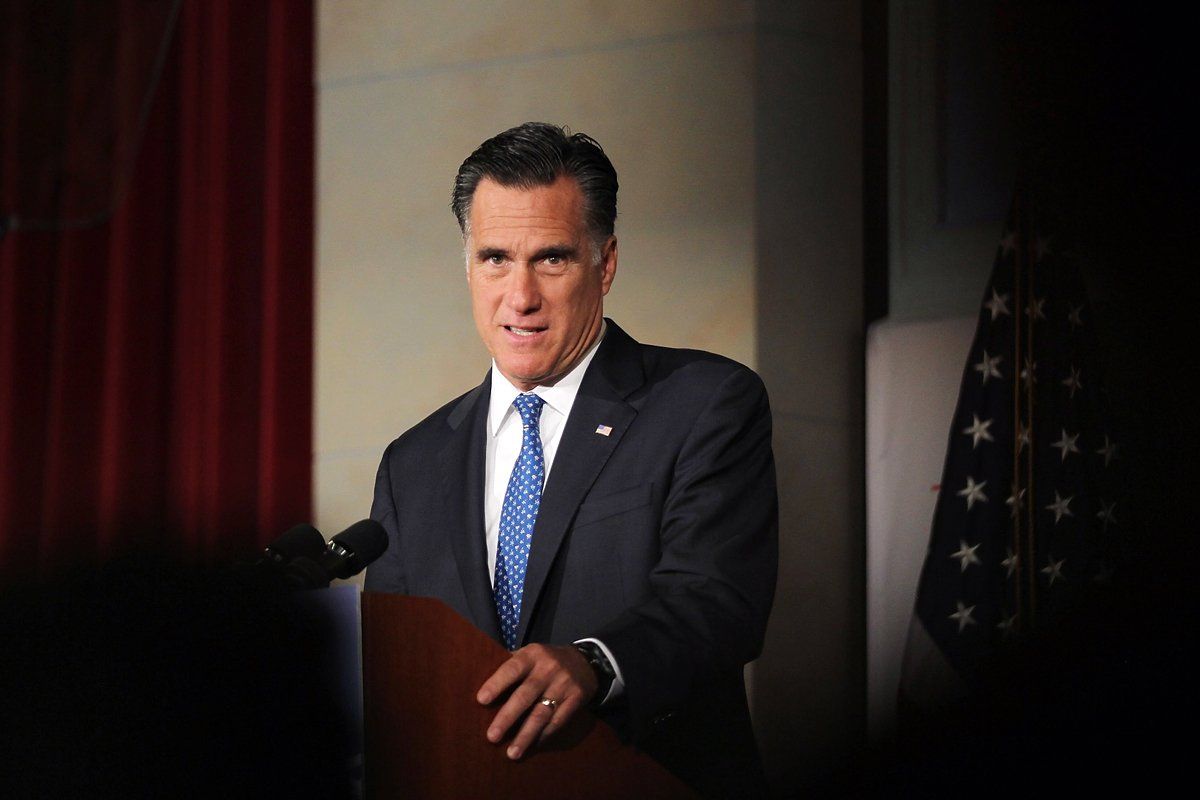

Voters are likely to know two things about Mitt Romney: that he's rich and that he's a Mormon. At the same time, more than one fifth of Americans tell pollsters they won't vote for a Mormon for president. Yet if Americans understood Mormonism a little better, they might begin to think of Romney's faith as a feature, not a bug, in the Romney candidacy. If anything, Romney's religion may be the best offset to the isolation from ordinary people imposed by his wealth.

It was Romney's faith that sent him knocking on doors as a missionary—even as his governor father campaigned for the presidency of the United States. It was Romney's position as a Mormon lay leader that had him sitting at kitchen tables doing family budgets during weekends away from Bain Capital. It was Romney's faith that led him and his sons to do chores together at home while his colleagues in the firm were buying themselves ostentatious toys.

Maybe the most isolating thing about being rich in today's America is the feeling of entitlement. Not since the 19th century have the wealthiest expressed so much certainty that they deserve what they have, even as their fellow citizens have less and less.

To be a Mormon, on the other hand, is to feel perpetually uncertain of your place in America. It's been a long time since the U.S. government waged war on the Mormons of the Utah Territory. Still, even today, Mormons are America's most mockable minority. It's hard to imagine a Broadway musical satirizing Jews, blacks, or gays. There is no Napoleon Dynamite about American Muslims.

This uncertainty about Mormonism's status in America no doubt contributes to the ferocious work ethic typical of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Mormons are taught to be "anxiously engaged in a good cause," in the words of Mormon scripture. Stephen Mansfield, the (non-Mormon) author of The Mormonizing of America, explains: "Mormons believe they are in life to pass tests set for them." The passage of repeated tests leads to self-improvement, ultimately to the point of perfection. In the words of early Mormon leader Lorenzo Snow: "As man now is, God once was; as God now is, man may become." From the point of view of Christian orthodoxy, that idea may be unsettling; as a spur to effort, it's unrivaled.

Like their Calvinist forebears, Mormons are inclined to interpret economic success as an indicator of divine approval, a fulfillment of the Book of Mormon's promise that the faithful will "prosper in the land." This prosperity gospel may explain some of Romney's defiant pride in his material success. Yet Romney's attitude toward money seems also to have been shaped by the LDS church's emphatic hostility to conspicuous consumption and lavish display.

According to his biographers Michael Kranish and Scott Helman, Romney was horrified when one of his Bain partners purchased himself a private plane. Yes, Romney bought a $55,000 car elevator. But for every story of a rich man's extravagance, there are many more of Romney's frugality: patched gloves, dented cars, and $25 haircuts.

If Romney's attitude toward money is influenced by his church, so is his outlook on how money should be used to help those in need. Mitt and Ann Romney have donated millions to the LDS church, a substantial portion of which has gone to its own internal welfare state for members in need. Unlike government aid, those who receive LDS welfare are expected to "give back"; they contributed almost 900,000 person-days in 2011. Here may originate some of Romney's skepticism about federal welfare programs.

Of course voters may also want to weigh some of Mormonism's more worrisome features. Just as 19th-century Mormons found themselves in profound conflict with the United States over the issue of polygamy, so could the theologically grounded commitment of today's LDS church to one-man-one-woman marriage place its members on a collision course with the 21st-century American mainstream, which increasingly accepts same-sex marriage.

And then there is the uniquely problematic character of Mormon scripture, which makes claims about people, events, and even whole civilizations for which there is no external evidence at all. Many Mormons maintain their faith by insisting that the best evidence of ultimate truth is found in a personal feeling that one's beliefs are correct. As a businessman, Mitt Romney was a brutally realistic analyst. But on the most important questions in his life, he may have closed his mind to unwelcome facts.

Yet, all told, the influence of Mormonism on Mitt Romney's attitude and outlook is far more positive than negative—and far more positive than millions of anti-Mormon voters seem to understand.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.