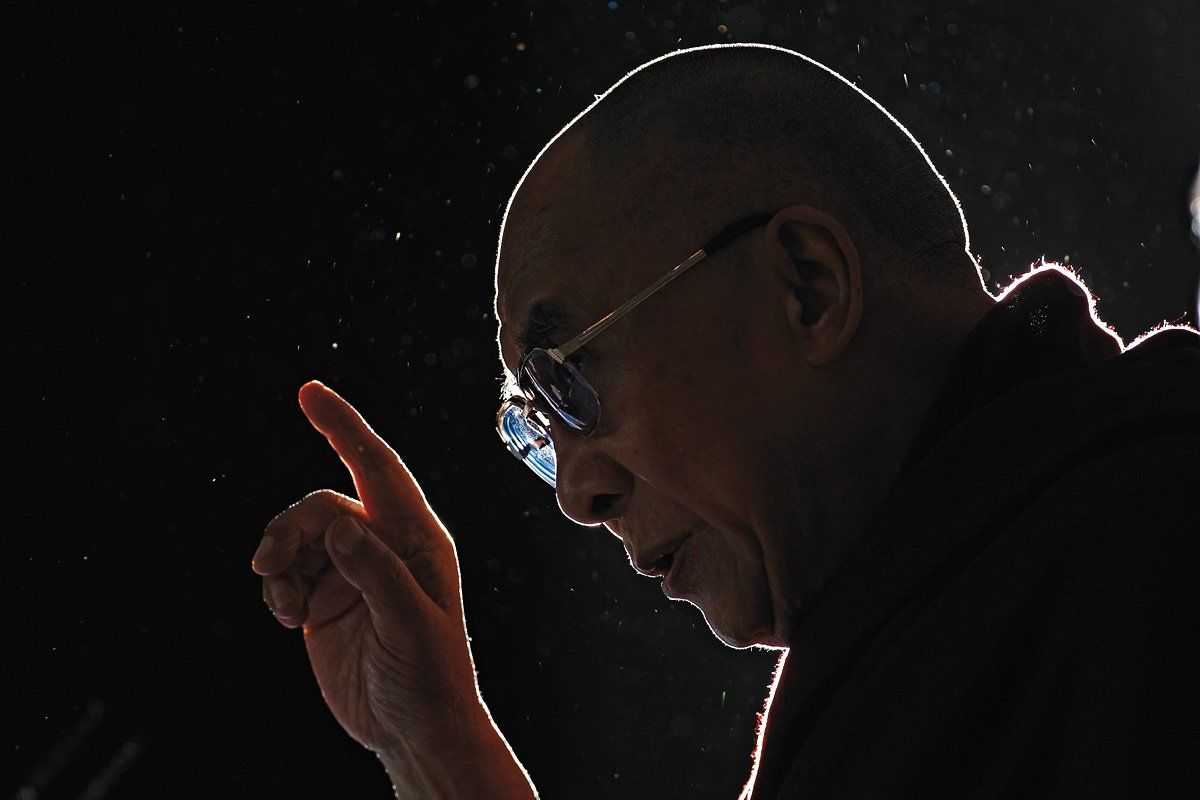

"I am a Buddhist-Marxist," says the Dalai Lama, and all the bankers in the room inhale sharply. "When I was young, I wanted to join the Chinese Communist Party." His Holiness gives a laugh like a kettle whistling, and reaches into the folds of his robes for a Kleenex with which to wipe his glasses. There are several other saffron- and maroon-robed monks in the conference room, all smiling benignly. They are joined by high-level financiers in pin-striped suits from the likes of JPMorgan Chase and Blackstone Group, and corporate lawyers, accountants, political pundits, entrepreneurs, and academics. The unlikely gathering takes place in London's Mayfair at the Legatum Institute, a think tank dedicated to finding innovative approaches to the free market in the 21st century. "Since the crisis, the search for a more ethical financial system has become a key issue," says Jeffrey Gedmin, president of Legatum. "We're looking for surprising perspectives on this."

"We've got to get people to trust us again," says a managing director of a large U.S. investment bank (most here speak on conditions of anonymity).

The bankers seem star-struck by the Dalai Lama's presence, though a touch cautious. ("He's a bit casual with the word greed," notes one.) His Holiness talks in Yoda-like epigrams—"Charity given without heart is like cheap clothes from China: looks fine at first but soon falls apart"—followed by those kettle-whistle-giggles.

"Will the financial system be improved by introducing more rules?" inquires Dalibor Rohac, a Czech economist and deputy program director at Legatum, who sports a yellow polka-dot bow tie.

The financiers smile at this. "You can make all the rules you want, but people will always find a way around," says an accountant. "After all, there's nothing illegal about off-shore accounts."

"Government cannot be a mother," says the Dalai Lama. "This is like feudal times, looking to a divine leader to tell you what to do." His attitude relaxes the financiers somewhat. "What do you think of high taxes on the rich, Your Holiness?" asks someone. "Rich should give to poor, but voluntary giving is much better," he answers. "Most important is for the poor to believe they can achieve something themselves."

"We're not all like Bernie Madoff," insists the director of an international-asset-management fund. "The trouble is structural: the earnings cycle has become so short you can only think about quick money. In the past you had companies which were family-owned, religious, rooted in the community. But in a globalized world, none of that holds."

Since the financial crisis, there have been attempts to return to some of these values. Companies classed as "benefit corporations," such as outerwear company Patagonia, are required by law to generate benefits to society as well as to their shareholders. Jitesh Gadhia, a director at Blackstone and a participant of the Legatum meeting, helped introduce the global business oath, part of which reads: "I will manage my enterprise with loyalty and care, and will not advance my personal interests at the expense of my enterprise or society."

Though marginal at present, such initiatives chime with the Dalai Lama's message, which emphasizes changes to individual behavior rather than a reliance on regulations. As he writes in his latest book, Beyond Religion: Ethics for a Whole World: "Ultimately the financial crisis was generated by greed itself —by the failure to exercise appropriate moderation and restraint in the blind quest for ever greater profits." The Dalai Lama proposes "secular ethics" training to counteract this. "Blood pressure goes down when there is more ethical behavior—studies have shown this," His Holiness tells the bankers with a chortle.

"Ethics training in financial institutions isn't necessarily new," says Jules Evans, author of Philosophy for Life and Other Dangerous Situations and an academic at Queen Mary, University of London. He cites Citigroup's five-point ethics plan devised by its former CEO, Chuck Prince, and launched in 2005 on the heels of a regulatory scandal. Practices included an ethics hot line and required training for all 260,000 staff members. Yet, as Evans notes, three years later, Citigroup was betting high on the U.S. housing market and selling toxic mortgage bonds to its clients.

"Most ethics training is performed perfunctorily," says Evans, who is designing new, more fundamental trainings. "The idea is to create a space where individual employees can regularly ask themselves whether their actions are ethical, and— just as important—can tell their bosses if they think their behavior is wrong."

The Dalai Lama says ethics training should take place in schools, with secular ethics classes worked into curriculums. Yet the issue starts even farther back, he adds: "If you have affection from your mother, then you are content. But if there is no affection from mother, then people become greedy, angry, insecure." Stressing family values, personal responsibility, and skepticism of government, the "Buddhist-Marxist" sounds like a compassionate conservative. The Lama and the bankers have more in common than one might think.

The Dalai Lama takes his leave, and the bankers, academics, entrepreneurs, and pundits rush to have their photo taken with him. "Can I have a picture with you for my mother?" asks one. "She doesn't believe I'm meeting you." As the monks file toward the door, the directors of investment banks and international asset managers stretch out their hands to say goodbye. Instead of shaking them, the monks grip the men's hands, pull them into their robes and press them to their hearts, holding them there just a little too long, all the while nodding at their counterparts with smiling eyes.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.