Medical research typically is a cautious, restrained affair—but every once in a while, scientists try out a radical idea. Take this one for example: injecting a live virus into someone with cancer on the off chance that the virus might go ahead and kill some cancer cells.

Nuts? Actually this approach, called viral oncolysis, has been around since at least the 1950s, when West Nile virus, thought harmless at the time, was injected into people with an array of advanced and seemingly hopeless cancers. Some got a little better, some a little worse, but the approach fell away, eclipsed by the promising new field of chemotherapy. Safety concerns related to handling and injecting a live virus were of little import at the moment, at least to scientists. (Those who have seen the 2007 Will Smith film I Am Legend will remember that in that fictional scenario, using a virus to treat cancer didn't work out so well, a plot that speaks to fears of a virus gone haywire.)

Well, time to pay attention once more—live virus cancer therapy is back. In a recent preliminary report from San Diego, a small group of patients with advanced liver cancer received doses of vaccinia virus, the same virus injected for more than 200 years to prevent smallpox. Patients were given either a high or low dose; those receiving the larger amount lived significantly longer, suggesting that perhaps the vaccinia was beneficial.

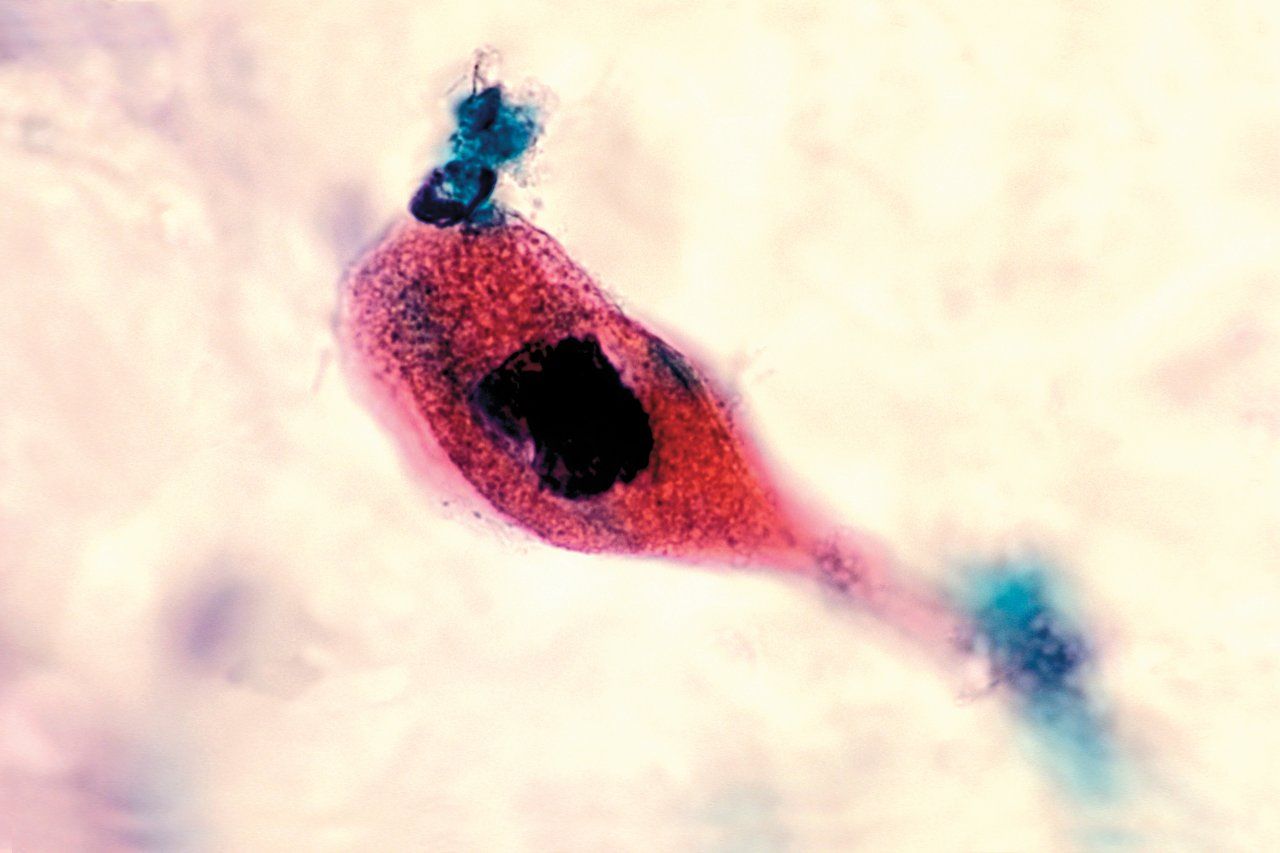

Viruses other than vaccinia are being examined as well, including herpes and adenovirus; the latter is a common cause of gastroenteritis and of pinkeye. Despite the extremely high-tech nature of the work, little is understood regarding how a virus kills a cancer cell. Some attack it directly. Others require scientific manipulation, which involves splicing in a bit of genetic material that is then delivered to a cancer cell, making it more susceptible to subsequent chemotherapy or radiation. Still others viruses are engineered to trigger a more pronounced inflammatory response from the patient's own immune system.

Each of these approaches is being actively developed, and many trials against a variety of advanced cancers are underway at hospitals in the United States and Europe. As with the San Diego findings, early reports can be intoxicating; almost unimaginable promise feels just around the corner. And viral therapy—using one disease to treat another—has a certain odd, irresistible logic to it.

Yet the thrill created by a wild and crazy concept must be converted into a workaday study. This includes enrollment of hundreds of patients into a meaningful clinical trial and the familiar slow grind of methodical science: measuring and remeasuring, anticipating and avoiding large bumps, changing plans while in midair. It is only here, in the dull gray overcast of scientific work, long after the sparkle of the big idea has worn away, that true progress is made.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.