By some measures, the world has never seemed more civilized. Murders, rapes, and even barroom brawls are down. Then came springtime in America, and with it kitten-killing, brain-eating, entrails-throwing, blood-spitting, naked al fresco face-devouring crimes that made Memorial Day feel like end times. After this "zombie apocalypse," as it was quickly dubbed, the federal government moved to restore order, noting no outbreak of a virus with "zombielike symptoms" and banning "bath salts," an amphetamine-like drug cocktail that may have played a role in some of the crimes. But the question remains: what's with all the craziness?

Every incident, of course, is its own sad story. But what if the cases, together, mean something more? Last fall Oxford research fellow Susan Greenfield warned that ignoring the way digital experience rewires the brain—literally "blowing the mind"—may one day be akin to doubting global warming. And in a video essay on YouTube, the writer Will Self argued that our wired world is "inherently psychotic," a place where a single screen hosts both the real and virtual life, with just a mouse click between them. Does the Internet cause insanity? No. But for some vulnerable souls, it may excite their already destructive states of mind.

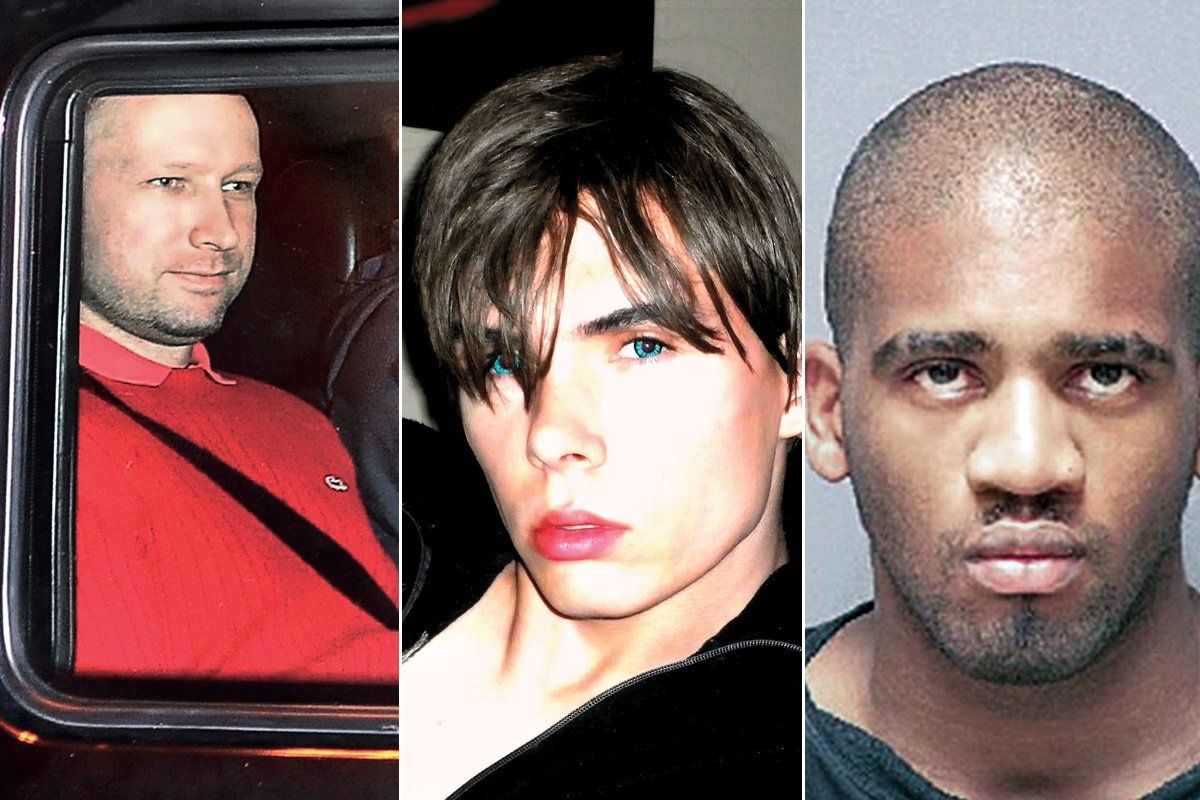

Consider two recent cases of zombielike depravity. Late last month, severed hands, feet, and a torso surfaced in three Canadian cities, along with a Web video of a young man eating pieces of his dismembered lover. The alleged killer, Luka Rocco Magnotta, was a social-media "whore," in the words of one criminal profiler, juggling several extreme online personas and reveling in the attention until he was arrested last week at an Internet café. He was reading his own news.

Then there's the ongoing trial of Anders Behring Breivik. Last summer, after several years of what he calls "full-time" Web surfing, including daily training on the shooting game Call of Duty, he killed 77 people in Norway. His virtual and real worlds became indistinguishable, according to expert testimony at trial. Andrew Keen, a Web entrepreneur turned critic of digital culture, agrees: "Breivik may be an extreme example," he wrote recently for CNN, but in a world where millions of people live as he did, "I fear there will be more young men like him."

Last June the U.S. Supreme Court acknowledged research showing that violent online videogames are a "social problem," even as free-speech concerns doomed a California ban on sales to minors. But last month a high-ranking British legislator suggested increased controls over some gaming content, following in the footsteps of China and South Korea. And yet the real issue may be broader: it is well established that city living—with its constant noise and lack of solitude—is linked to higher rates of insanity; now research is showing that our nonstop connectivity may duplicate this stress, pushing unsteady minds toward full-blown mental illness. A new study adds "The Truman Show delusion" to the ranks of Internet-related illnesses. As of press time, zombie delusions remain undiagnosed. But its sufferers already walk among us, these undead tech addicts, their armies always expanding.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.