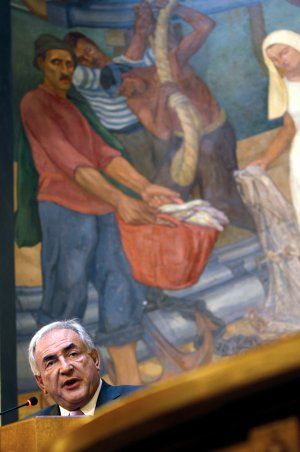

Dominique Strauss-Kahn is on top of the world right now, but maybe that's not where he really wants to be. Almost by default, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund keeps accruing power in the midst of crisis.

Two years ago, when the global economy teetered on the brink like a house in a mudslide, the newly formed group of the world's 20 richest countries turned to Strauss-Kahn and the IMF to help shore up the foundations. Late last month G20 ministers went back to Strauss-Kahn, seeking his assistance to avert a currency war and proposing to double the IMF's fiscal resources.

Strauss-Kahn, 61, has never experienced quite so much adulation, nor, indeed, affirmation of his centrist political and economic views. As France's finance minister in the Socialist government of Lionel Jospin during the 1990s, Strauss-Kahn was obviously at odds with his party's own ideologues. He managed to get the government to embrace the euro, he pushed through massive privatizations of state industries, he cut taxes, and he allowed stock options. Indeed, such was his record that even The Economist bid him a "sad adieu" when he resigned. But his subsequent career sank into a mire of public confusion about his policies and motives.

Now DSK, as he's called, finds himself not only at the top of the international financial system, but at the top of France's opinion polls. And that presents him with a problem: should he try to stay on at the IMF in this pivotal role on the world scene when his first term there expires in late 2012? Or should he resign and return to France next year to run for president in early 2012? The clock's ticking.

Those same polls show that if the French vote were held today, Strauss-Kahn would have a commanding lead over the wildly unpopular right-wing incumbent Nicolas Sarkozy. As a columnist in the French weekly L'Express articulated Strauss-Kahn's enviable choice: "Either DSK serves France by declaring his candidacy for the presidency, or he serves it, as well, by saving the global economy at the IMF. It's a grandiose dilemma of the sort any politician might dream."

Close friends and colleagues of DSK, requesting anonymity in order to speak more candidly, feel sure he'll be on the hustings at some point. A few, after reading political omens—and the man—think they can predict when. "He's very careful not to say it, because the moment he gives an indication this is what he's planning, he will have to leave the [nonpartisan] IMF," says a friend whose relations with DSK go back decades. One of his female acquaintances points out "the diet he's on at the moment," which she said is most likely the portly politician's preparation for television appearances. More substantively, a former adviser suggests he would want to make the announcement of his candidacy in June after a G20 summit expected to be held in France in May where he could "be at the helm of the IMF and use it as a platform."

But, as DSK knows only too well after a miserable failed bid for the Socialist Party's nomination in the 2006–07 political season, becoming a candidate is not the same as becoming president. And the IMF platform may have become so important over the last two years that it will be hard to give up if, as seems likely, he has a good chance to keep it for a second term.

One of the ironies of French political life is that in 2007 DSK landed the IMF post with solid support from the newly elected Sarkozy. Indeed, the French president was credited with a Machiavellian masterstroke that showed his willingness to work with prominent Socialists while at the same time eliminating, or at least compromising, them as potential rivals. At the time, as seen from Paris, the IMF seemed a sort of bureaucratic backwater of accountancy on the far side of the Atlantic.

Only months into his new job, however, DSK had a clear and alarming vision of the clouds gathering on the economic horizon. At Davos in early 2008 he called for fiscal and budgetary measures on a global scale to meet the coming crisis, and some observers were amazed to hear the IMF chief advocating pushing states toward stimulus measures. Samuel Brittan of the Financial Times wrote that "some reacted as if the Pope had embraced the teachings of Martin Luther." Economist Larry Summers, as surprised as anyone else, was quoted as saying, "This is the first time in 25 years that the IMF managing director has called for an increase in fiscal deficits, and I regard this as a recognition of the gravity of the situation that we face." According to Alexandre Kara and Philippe Martinat in their recent book, DSK-Sarkozy: Le Duel, the IMF board pointedly reminded Strauss-Kahn of the fund's orthodoxy. But DSK held his ground. "With what's waiting for us, you're going to see us resort to budgetary expenditures more often than you think," he's reported to have said. Then, sure enough, the storm hit in September 2008.

By the spring of 2009, when the G20 met in London, world leaders stunned by the extent of the economic crisis "turned to DSK," according to Kara and Martinat. They increased the IMF's resources to $750 billion to try to restore an even keel. "It was a triumph for the man from France," say his French biographers.

Since then, Strauss-Kahn has taken to speaking with ever more confident authority as he seeks to shape the world's economic future. "We gather at a pivotal moment in history, facing an uncertain future," he told the IMF board in September. Growth is coming back, but "the recovery is fragile and uneven—and fragile because it is uneven," with Asia, Latin America, and even Africa returning to growth much faster than in the past, while Europe is "sluggish" and the United States "subdued." DSK said he doesn't expect a "double dip" recession, but talked about four critical risks that have to be avoided:

On the question of public debt, "the biggest threat to fiscal sustainability is low growth," he said, and defended continued stimulus spending where needed except for "those countries that are on the edge of the cliff": "Nobody would expect that the advice of the IMF to Germany will be the same as the advice of the IMF to Greece." The second major problem is "a jobless recovery," said DSK, and by extension "the risk of a lost generation" if GDP growth does not convert to job growth. Thirdly, financial regulation is important, he said, but financial supervision is even more vital. If rules are not implemented, "it is as if you did nothing." And finally, there is the problem of "the vanishing of the commitment to cooperation" among nations. Leaders worked together to stop a second Great Depression and "avoided that altogether," DSK told the IMF board, but now they're pulling back, turning inward.

Strauss-Kahn's vision is nothing if not broad. He told the IMF board that the two centuries of the Industrial Revolution, when relatively small countries could dominate world markets and world politics because they dominated certain technologies (think guns and steel, but also textiles, communication, and high-yield agriculture) are gone. Now technology is globally shared and, as was the case a few hundred years ago, it's likely that "the strength of a nation will be measured by population." Without getting into any real specifics, he predicted the adjustment to this new reality will take "a decade or two," but as in the distant past, "a large country is very likely to be stronger than a small country."

So given that vision, it's not unfair to ask if France is a big enough stage for Strauss-Kahn. As a point of fact, Sarkozy himself has found the French presidency more limited and constraining than he would like and has thrived in office only when he has been able to cast himself as leading Europe. Sarkozy clearly is looking forward to his country's turn heading the G20 over the coming year—if he can only take the spotlight away from DSK.

At times, Sarkozy and DSK really do seem born to be rivals: both grew up outside the traditional French elite, knocking on its door, then battering their way toward the top. Sarkozy's father was a Hungarian émigré; Strauss-Kahn's family is Jewish, and he spent his childhood in Morocco. Neither went to the elite École Nationale d'Administration, the accustomed training ground for top politicians. (DSK eventually taught there.) But Sarkozy has proved on many occasions that he has a genuine cynical genius for politics, while DSK's record is not so clear. "I'm not yet absolutely convinced that he is a great politician," says Gérard Grunberg, who has written extensively on Socialist Party politics. "And I am not absolutely convinced that he is able to run a great election campaign."

For all Strauss-Kahn's economic acumen and his current political luck, should he decide to take the plunge into the presidential contest, he is likely to face, again, many of the same political and personal problems that have hampered him in the past.

The least of Strauss-Kahn's worries in the French context is likely to be his well-established reputation as a skirt-chaser. Before DSK went to Washington, a columnist for the Paris daily Libération cautioned that his "only real problem" there could be "the way he relates to women." The IMF's morals are "Anglo-Saxon," Jean Quatremer wrote on his blog, and "an out of place gesture, an allusion that's a little too precise" could lead to a media circus. Sure enough, in 2008 the IMF looked into an alleged one-night stand DSK had with a Hungarian economist at the fund. The brief investigation concluded the affair was regrettable and reflected poor judgment, but DSK kept his job. He also kept his wife of 20 years (his third), the celebrated French television interviewer Anne Sinclair, who subsequently told reporters she'd known about the Hungarian woman a year before the story broke. Back in France, few voters would find such stories scandalous, and Sarkozy, one might note, also has been married three times among multiple liaisons.

More problematic—and possibly fatal to his presidential chances—is the way DSK relates to his own Socialist Party. And when it comes to winning elections, or trying to, DSK the moderately left-wing economist has been known to advocate radically impractical policies to shore up his party's support on the far—and even the extreme—left. In 1997, for instance, he fully supported the 35-hour workweek, and some Socialists say he actually came up with the idea, although his fellow minister, Martine Aubry, served as the leading public advocate for the policy. DSK's current IMF post doesn't allow him to speak his mind on French politics, and staying above the fray clearly hasn't hurt him in the polls. So friends and foes are left to divine his mind—What Would Dominique Do?—on issues like the pension reform that has riled the French. DSK's saying that French retirement at 60 shouldn't be read as "dogma" is read in countless ways, and, for now, mostly to his political benefit.

The problem comes when he hits the campaign trail. In 2006, vying against a field of several contenders for the Socialist Party presidential nomination, DSK implausibly but insistently embraced the rhetoric of the far left. The privatizer of the previous decade was suddenly pleading for "temporary nationalizations" of strategic companies. "The people he really listened to were the Trotskyites, if you can imagine that," said one long-time colleague now in the private sector. In the end, DSK lost the confidence of the country's political center without gaining the trust, or the votes, of the more extreme elements in his own party. Ségolène Royal got the nomination, then lost the race to Sarkozy. "Strauss-Kahn has a real ability to defeat himself," says his former colleague.

Political analyst Grunberg thinks DSK will be freer to speak his centrist mind next year than he was in 2006, but will still have the problem of the left of his own party and the many splinter groups that are out on the fringe but can still play an important role at the polls. "It isn't so simple to run a campaign against your support," says Grunberg.

Meanwhile, however, other potential Socialist candidates are getting ready to run. The most serious contender at the moment is Aubry, now the party's head. She might step aside if DSK enters the race, but he needs to make up his mind soon, if he hasn't already. It's a tough call—and one that most other politicians can only wish they had to make.

Christopher Dickey is also the author most recently of Securing the City: Inside America's Best Counterterror Force—The NYPD, chosen by The New York Times as a notable book of 2009.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.