Whatever America's problems with the legislative branch—and given the institution's 21 percent favorable rating, there are clearly many—no one can call the 111th Congress a "do-nothing Congress." The Senate's passage of the financial-regulation bill is only the latest achievement in what has been a historically, almost maniacally, productive session.

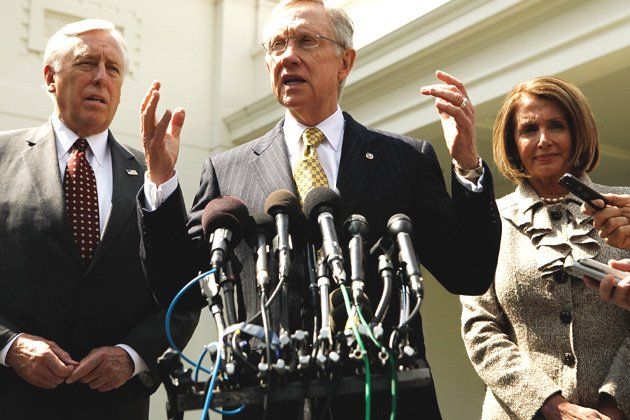

Under Harry Reid and Nancy Pelosi, Congress has passed a historic health-care reform bill, an $800 billion stimulus, Ted Kennedy's national service act, legislation regulating tobacco, multiple jobs bills, and much more. These bills were imperfect, but in more cases than not, they were huge, even historic, steps forward. And aside from health-care reform—which is, admittedly, a big aside—they were all popular when they passed.

So maybe Congress isn't as broken as some (like, well, me) keep saying? Color me skeptical, for at least a few reasons.

First, this Congress benefited from a rare alignment of political power. Democrats had a large majority in the House, which isn't all that uncommon. But more important, Democrats in the Senate had 60 votes, which hasn't happened since the 1970s, and then 59 votes, which is also quite rare. That made filibusters relatively ineffective: as long as Democrats could hold their own members and, after they lost Kennedy's seat, pick up one Republican, they could pass legislation. But such large majorities are infrequent in American politics. Much more common is a majority in the low to mid-50s, which is when the filibuster becomes most effective and the minority can bring almost all legislative action to an immediate halt. It is hard to imagine how anything major would have gotten done this year if Democrats had had 53 votes rather than 59.

Second, Congress is likely to lose some of its more moderate members this year. Arlen Specter is already done, having lost the Democratic primary to Joe Sestak—and this was after he left the Republican Party in 2009 because he was going to lose that primary to Pat Toomey. Blanche Lincoln is heading to a runoff with Bill Halter in Arizona. Bob Bennett—who's not one of the more moderate members but is willing to work across the aisle—was kicked out by Utah Republicans who were irritated by his bipartisan tendencies. John McCain, who has also been willing to break ranks at certain points in his career, is facing a tough primary challenge in Arizona. Evan Bayh decided to retire. All of these senators will be replaced by someone, whether from their own party or outside, who is more reliably partisan.

The issue there is not simply that there will be fewer moderates in Congress, but that the moderates who remain will be cowed into a more reliable form of partisanship. After all, if a reliable, influential conservative like Bob Bennett and a well-known veteran like Arlen Specter can lose their primaries, no one is safe. And if no one feels safe, no one will be able to cast the sort of difficult, heterodox votes that annoy the base but are necessary for an institution that requires those votes to keep functioning. The result will be that the remaining moderates stop acting so moderate.

Third, the fact that Congress is passing legislation doesn't mean it's doing a very good job of it. Take financial regulation. Chris Dodd developed the bill and passed it out of his committee in literally 20 minutes. That meant there was no time for debate or discussion or amendments. The bill was given more time on the Senate floor, but not nearly enough: Harry Reid called a cloture vote before some of the most important amendments, like Maria Cantwell and John McCain's proposal to reinstate the Glass-Steagall wall separating investment banks from commercial banks, even got a vote.

Reid wasn't trying to be callous: the Senate had to preserve time for a vote on war funding and an extension of unemployment benefits. But that gets to one of many problems with the Senate's current functioning: there's not enough time. A little-known side effect of routine filibusters is that everything takes a lot longer. Breaking a filibuster—even if you have the votes—takes about three days of mandatory time, and multiple filibusters can be launched against the same bill. When there's less time but not less to do, quality suffers.

So too do some smaller issues that the harried Senate judges unworthy of the time they'd take. You see this most clearly in nominations. Right now, there are more than 90 appointees who have been passed out of committee but haven't gotten a vote on the Senate floor. These are people like Rafael Borras, who would be undersecretary for management at the Department of Homeland Security (and by all accounts, DHS could use some better management), and Eric Hirschhorn, who would be the undersecretary of commerce in charge of exports. These are positions we need filled if the government is going to work well. But they're not getting filled because senators are filibustering the nominees and the majority doesn't have time to break the filibuster.

In most cases, the nominees are not even controversial. Lael Brainard, now undersecretary of international finance at the Treasury Department, was held up for a year before finally seeing a vote—and then she got the support of more than 70 senators. Rather, senators are using the threat of holding these nominees up in order to get concessions on unrelated issues. At one point, Richard Shelby (R-Ala.) put a hold on all nominees because he wanted to protect pork projects in Alabama. Even more absurdly, Jim Bunning (R-Ky.) held up a Trade Department nominee because he wanted the government to become more supportive of candy-flavored cigarettes. Seriously.

So is Congress working well? Not really. Some of its dysfunctions have been partially obscured by uncommonly large majorities and a moment that made uncommonly bold action possible. But the test of a political system is not how well it functions when everything is in its favor. It's how well it functions when things get hard. And neither the everyday workings of the body nor the trends that we're beginning to see in the 2010 election should make anyone feel too comfortable.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.