A commonly used drug may be the secret to a longer, healthier life, new research suggests.

Aging is a complex process, which many of us consider to be an inevitable consequence of life on Earth. But thanks to modern technology, many scientists now consider aging to be a disease that we can treat, or at least delay.

"You can think about life span like a candle—it depends on how fast it burns," Michael Lisanti, a professor in cancer research and metabolism at the University of Salford in Manchester in the U.K., told Newsweek. "We can make the candle burn longer."

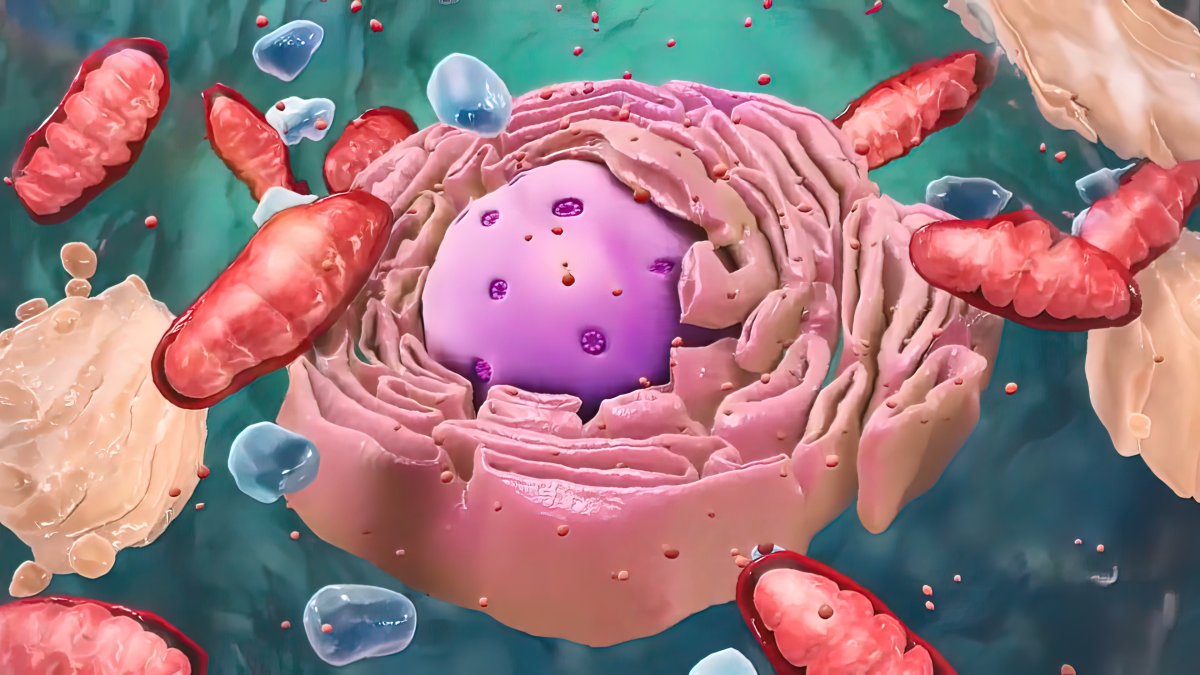

But to slow the process of aging, we must first understand why it happens. One of the leading theories for why we age focuses on the microscopic powerhouses that live inside our cells: mitochondria.

Mitochondria contain the microscopic machinery that our bodies need to turn sugar into energy. However, the process can result in the production of dangerous waste products that build up over time and damage the mitochondria's delicate machinery.

"There's a lot of literature to suggest that, in aging cells, the mitochondria are somehow defective, mostly due to oxidative stress," Lisanti said.

But if we were somehow able to slow these cellular powerhouses, the toxic waste products would build up more slowly, ultimately resulting in slower aging and a longer lifespan. So how can we slow the mitochondria without affecting the rest of the cell?

"Mitochondria are like little organisms inside cells, and they actually have their own DNA and make their own proteins," Lisanti said.

Scientists believe that, billions of years ago, mitochondria were once free-living organisms—a type of bacteria. One day, these bacteria were engulfed into larger cells where they began to produce energy for their host cells in exchange for food and shelter. Over time, they began to exchange DNA with the host cell so that they could no longer live on their own.

"They've sort of been tamed," Lisanti said.

However, because of this evolutionary history, mitochondria appear to be susceptible to some of the same drugs that target bacteria—specifically, antibiotics. If used in moderation, these drugs won't kill the mitochondria. But they will slow them.

"You're essentially turning down the volume on the mitochondria," Lisanti said. "And the idea is that if you slow down the mitochondria, like turning the volume on the radio down, then you can prolong lifespan.

In a study published in the journal Aging on November 22, Lisanti and his team from the University of Salford investigated how different antibiotics might effect the mitochondria of microscopic worms called C. elegans, and ultimately how this could affect the worms' lifespan.

"We didn't just use any antibiotics," Lisanti said. "They were carefully selected because these are antibiotics that inhibit the [protein building machinery] of the mitochondria."

Specifically, the team looked at two antibiotics—doxycycline and azithromycin—which target different component's of a bacterium's (or, in this case, a mitochondrion's) protein-making machinery.

"The good news is that these two drugs are both FDA approved and have been for many years," Lisanti said. "In the case of doxycycline, it's an antibiotic that's widely used for the treatment of acne. And people will take it for over six months, even years, at a time. It's a very well-known drug and it's over 50 years since it was FDA approved."

The team tested the two drugs individually and in combination at different concentrations to monitor the effects they had on the worms' lifespan. And the results were impressive.

In all groups, the antibiotics increased the median age of the worms while reducing observable markers of aging. Using the two drugs in combination yielded particularly exciting results, with a near doubling in average lifespan even at lower concentrations.

"If you hit two different targets that have the same purpose, then you can dial down the concentration," Lisanti said.

Of course, when we think about antibiotics, two immediate concerns arise: 1) how might this affect the essential colonies of microbes that live in our guts and; 2) how can we avoid adding to the ever-growing crisis of antibiotic-resistant superbugs?

"One idea would be to make an analogue that is no longer an antibiotic and targets only the mitochondria," Lisanti said. "That would eliminate the issue associated with the microbiome and also with the drug resistance."

In a previous study, the team already demonstrated how a synthetically produced molecule with the same properties as an antibiotic could be used to target certain cell types without affecting other resident microbes.

"We also were using the drug at much lower concentrations so it would be less likely to affect the microbiome," Lisanti said. "You could potentially also take it with a probiotic."

While the gains made in lifespan seen in this study are impressive, slowing the aging process is not Lisanti's only goal.

"There's a big association between aging and cancer," he said. "And the idea is that, potentially, if we can prevent aging, we can also prevent cancer because the number one risk factor for cancer is aging.

"Our ultimate goal is to find existing FDA-approved drugs and dietary supplements that can not only increase lifespan but also improve healthspan."

The idea to study the role of antibiotics in the body originally came from his daughter, in the context of fighting cancer.

"My wife and I are both scientists, and we were talking about cancer because we sometimes talk about experiments at the dinner table," Lisanti said. "So to keep my daughter—who was 8 at the time—from getting bored, we asked her how she would cure cancer. And she said [she would treat it] the way you would treat a sore throat: with antibiotics. And that was really the moment where we started looking at antibiotics and cancer, which eventually led to looking into antibiotics for aging, as well."

More work is needed to fully understand the anti-aging properties of these drugs, particularly in humans, but the results provide an exciting proof of concept.

"We have to start somewhere," Lisanti said. "And this worm is actually a very established model for aging. It's a simple organism but is governed by many of the same principles."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Pandora Dewan is a Senior Science Reporter at Newsweek based in London, UK. Her focus is reporting on science, health ... Read more