Knightsbridge. London. 2007. Boris Berezovsky, a.k.a. "the Godfather of the Kremlin," is shopping at Dolce & Gabbana.

As the stocky Russian, a sworn enemy of President Vladimir Putin, leaves the store, he notices Roman Abramovich, a.k.a. "the Stealth Oligarch"—one of Vladimir Putin's closest allies—shopping next door at the elegant, and pricier, store Hermès.

For seven long years, he has waited for this opportunity. Bustling past Abramovich's bodyguards, he bursts into the luxury boutique. "I have a present for you," he tells his onetime protégé triumphantly. "This is to you—from me!"

The older oligarch throws a piece of paper at the man he once thought of as a son. But the younger Russian recoils, and the piece of paper—a writ in a $5.6 billion private litigation case, the biggest ever filed anywhere in the world—flutters to the floor.

Thus begins the public part of a story that, at times, seems scripted in Hollywood with its colorful cast of billionaire characters, its armored yachts, casual assassinations, money-stuffed suitcases, and Kremlin intrigue. Played out in front of a rapt audience in a London courtroom, it reveals a lot about power plays in Russia, and Putin's rise and his consolidation of control.

As Berezovsky himself describes it in court proceedings later: "This is a very Russian story—with lots of killers, where the president himself is almost a killer."

The story takes off in 1994, on a private yacht in the Caribbean, during a holiday cruise for some of Russia's richest men. Always in motion, chattering incessantly on the phone, Berezovsky, who bears a passing resemblance to the Penguin in Batman Returns, is at this point Russia's most famous tycoon.

A brilliant math professor, he has been quick to understand how to successfully navigate the postcommunist economy. His car dealership, the first in Russia, makes money by delaying payments to gullible manufacturers with no concept of inflation. He is among the few businessmen in President Boris Yeltsin's inner circle, known as "the Family."

But such success comes at a price. On the cruise, Berezovsky's hands are covered with scars: a month earlier, he has barely survived an assassination attempt—a kilogram of explosives detonated next to his car, decapitating his driver. (In a city rife with gangsters, it was the 53rd bomb attack in Moscow that year.) But the near-death experience has transformed Berezovsky, apparently convincing him he needs direct political power to make Russia safe for business.

Quick to grasp that television can influence politics, he has acquired control of Russia's biggest channel. But he now needs money to run it. During the trip on the yacht, he is scheming, laying plans.

Berezovsky knows most of the men onboard, but there is one new face: the shy-seeming, slightly unkempt, meekly smiling Roman Abramovich, who at 28 is 20 years younger than Berezovsky. Orphaned as an infant, Abramovich has been raised by a kindly uncle and, a business natural, has worked his way up to become a successful oil trader. Now, as the men are relaxing on the yacht, Abramovich is using the opportunity to ingratiate himself with Berezovsky. "He is very good at getting people to like him," Berezovsky will later testify, somewhat bitterly. "He is good at appearing to be humble."

On the yacht, Abramovich proposes a plan that will help Berezovsky pay for his TV channel. If Berezovsky uses his Kremlin connections to force the privatization of two state oil assets, Abramovich will merge them with his trading firms to create an oil major.

The two shake hands on a deal to create Sibneft, a company that eventually will be worth more than $13 billion. Nothing at all is put on paper. And what exactly is agreed upon during the Caribbean cruise is at the heart of the matter. Along with an alleged threat by Abramovich, it is the main bone of contention today, 18 years later. Berezovsky claims the agreement was to share the oil company 50-50; Abramovich says the deal was for the company to be his alone.

What no one disputes is that after the 1994 cruise Berezovsky started lobbying President Yeltsin to put the oil assets up for auction, arguing that, with the oil money, he could run a well-funded channel that, in turn, would help the ailing president's reelection. On the day of the auction itself, Berezovsky recalled how he was in top form, negotiating furiously in the corridors, getting one rival to bid lower in return for favors, another to withdraw if he paid off his debts. It wasn't fixing, he later told the court. "I just find the way through! In my terminology, that's not fixing."

The plan hatched in the Caribbean worked to perfection. In 1996, backed by Berezovsky's TV channel, Yeltsin pulled off an unlikely election win.

Berezovsky reaped rewards, too. He joined Yeltsin's administration and became a true powerbroker: negotiating a hostage release with Chechen terrorists one moment, creating a new political party the next. He was one of the few guests at Rupert Murdoch's wedding. Forbes estimated that Berezovsky was among the top 10 most influential entrepreneurs in the world. But he wanted more. "There was something of the megalomaniac about Berezovsky that would lead to fantastical proclamations on his part," Abramovich testified during the trial. "One of his ideas was to return monarchy in Russia. The grander the plan he entertained, the more cash he would be after."

And while Abramovich got on with the more mundane task of running Sibneft—spinning off a web of offshore firms or setting up trading companies staffed with disabled employees to take advantage of tax exemptions for the handicapped—Berezovsky used his beloved TV channel to gain ever more fame, clout, and notoriety. He also had time, it seems, for a little shopping.

As became evident in trial testimony, between 1996 and 2000, Berezovsky contacted his "protégé" Abramovich regularly. He called from France to ask for $27 million to buy a chateau; from London to buy baubles for his girlfriend. When Berezovsky needed $5 million in cash, they were delivered in five bulging suitcases.

Every year, tens, sometimes hundreds, of millions were transferred by Abramovich to Berezovsky. Berezovsky claimed the transfers show he was a co-owner of Sibneft; Abramovich said the payments were to keep the political godfather happy, describing Berezovsky as his "krisha"—meaning "roof," a term that denotes protection in the Russian mafia lexicon.

Around the time of the 1996 elections, Berezovsky introduced Abramovich to the Family. At Yeltsin's garden parties, a guest recalled, Abramovich barbecued kebabs and poured wine, going so far in his desire to be helpful that one guest allegedly mistook him for a waiter. But the chivalrous attitude was well received among members of the Family—a contrast to the uppity Berezovsky. Soon, Abramovich had established himself as a trusted confidant and benefactor—if a quiet one at that. When, in 1998, a television program described him as "the wallet of the Yeltsin family," there were no pictures to accompany the description as his progress had been mostly off-radar.

Abramovich was not the only gray yet young thing Berezovsky was maneuvering into a position of influence during the 1990s. Another protégé was a certain Vladimir Putin, a former KGB lieutenant colonel so bland his nickname was "the Moth." Remembered as always wearing the same mucky, pea-green suit, Putin helped Berezovsky set up a car dealership in St. Petersburg, Berezovsky recalled. "Our relationship was based on mutual interests and mutual goals," Berezovsky recalled during the trial.

Berezovsky also introduced the Moth to the Family, inviting Putin along on skiing holidays at his Swiss chalet. And Putin rapidly rose from a desk job in the St. Petersburg City Council to head of the FSB, the former KGB.

Meanwhile, the Yeltsin regime appeared to be sinking. Berezovsky came under investigation for embezzlement, and rivals began to close in. Desperate, the Family launched a quest to find a trusted heir to Yeltsin. And apparently they thought Putin would be the right man. In court, Berezovsky recounted how he flew to a secret meeting with the Moth in Biarritz where, he claimed, he persuaded a reluctant Putin that he should be the next leader of Russia.

No sooner had the little-known Putin taken power than Chechen terrorists had detonated a series of bombs in Russian apartment blocks, killing 293. When Putin launched the Second Chechen War, Berezovsky's TV channel backed him, transforming the Moth into a heroic strongman. And the following year, as the country went to the polls to elect a new president, Berezovsky's channel went all-out for Putin, burying his rivals under verbal mud until they spent more time fighting the channel than dealing with Putin.

The Moth was victorious.

"How dull," Berezovsky told the liberal politician Boris Nemtsov, "I've got the country in my pocket." But, Nemtsov recalled, "Putin would never forget or forgive how Berezovsky created him."

As soon as he had captured the Kremlin, Putin started to show his true colors. He centralized power and ordered the oligarchs to stay out of politics. Still convinced of his own omnipotence, Berezovsky grandly announced he would build a "constructive opposition to the new authoritarianism." When a Russian nuclear submarine sank in the Barents Sea, Berezovsky's channel repeatedly attacked Putin, accusing him of being heavy-footed and failing to save the sailors on board. Afterward, Berezovsky was summoned to the Kremlin. Unusually, Putin kept him waiting. When he finally emerged, the president addressed him by the formal "vy," not their usual friendly "ty," Berezovsky recalled in court.

According to Berezovsky, Putin demanded he give up his beloved TV station. But Berezovsky refused. Soon, he was fighting a corruption investigation into his business with armed, balaclava-clad police raiding his offices. Berezovsky apparently realized that he'd completely misread the Moth, and he moved to France.

Berezovsky still hoped his protégé Abramovich would help in his battle with Putin. But it seemed Abramovich's loyalties had shifted.

Berezovsky testified that Putin had asked them both to contribute to a $50 million yacht he wanted. Berezovsky said he refused, sure that Abramovich would do so, too. Later, however, he came to believe Abramovich went behind his back and bought Putin the yacht himself, telling the new leader Berezovsky had refused to make a contribution. "I think this was the turning point in my relationship with Mr. Putin," Berezovsky drily noted on the stand.

But according to Berezovsky, Abramovich's greatest betrayal came in 2001. Instead of helping his old mentor when he needed it, Abramovich turned on him, demanding Berezovsky hand over his share of Sibneft at a knock-down price—or else Abramovich would use his new influence with Putin to keep one of Berezovsky's best friends locked in a Russian jail, Berezovsky testified during the trial. "He acted more and more like a gangster," Berezovsky lamented. "It was finally clear to me how ruthless Mr. Abramovich was."

Cornered by the man he had once considered close to a son, Berezovsky sold his share of Sibneft for $2.5 billion—about $5 billion less than its estimated worth.

According to Abramovich, Berezovsky was a friend, a valued mentor but also a political player whose palms needed constant greasing. The $2.5 billion, Abramovich testified, was the final payoff to Berezovsky—a thank-you for political services rendered. "I was very grateful to him that he helped me. I could never have achieved my results without his help," he told the court.

For the past dozen years, Berezovsky has lived as a political exile in Britain. His fortune is dwindling. The man, who by his own admission helped bring the Moth to power, has dedicated his life to dethroning Putin—but to little effect. In Russia, his old TV channel, including many of the journalists who used to support him, now portrays him as a caricature villain, a Penguin to Putin's Batman, a useful scapegoat for all conspiracies.

During the trial, whenever he was caught on discrepancies in his testimony, he clutched his balding head and stared furiously at the evidence, desperately searching for some genius formula to escape his own contradictions. But the mathematician-Machiavellian may have been trapped in his own schemes. He alleges (as do more objective voices) that Putin and the FSB were behind the terrorist attacks that became a catalyst for the Second Chechen War. But such allegations, of course, raise the specter of his own involvement in Putin's rise.

Meanwhile, Abramovich has prospered as one of Putin's favorites. Forbes estimates his fortune at $12 billion, making Berezovsky's remaining hundreds of millions look paltry by comparison. To rub salt into the older man's wounds, Abramovich has also moved to the U.K., where his exploits, as the third-richest person in the country, are closely followed by the press. Chelsea, the football club he owns, won the European Championship. While Berezovsky has sold his luxury yacht, Abramovich has bought the world's largest—complete with missile detection system and escape submarine. Abramovich's French Riviera chateau, which once belonged to Edward VIII and Mrs. Simpson, dwarfs Berezovsky's property. Rupert Murdoch, Russell Simmons, and Martha Stewart were reportedly guests at his New Year's Eve party. And when Prince Charles was late for a polo match, Abramovich lent him his helicopter.

Despite his high-powered toys and friends, he still manages to come across as the boy next door, liked by everyone he encounters—liberal journalists and former KGB apparatchiks alike. As Yeltsin's daughter once admiringly remarked, "Roman knows how to make friends."

And Sibneft, the company at the heart of this case and which was originally acquired from the state for slightly more than $100 million? Abramovich sold it back to the state—or rather, the state-controlled Gazprom—for $13 billion.

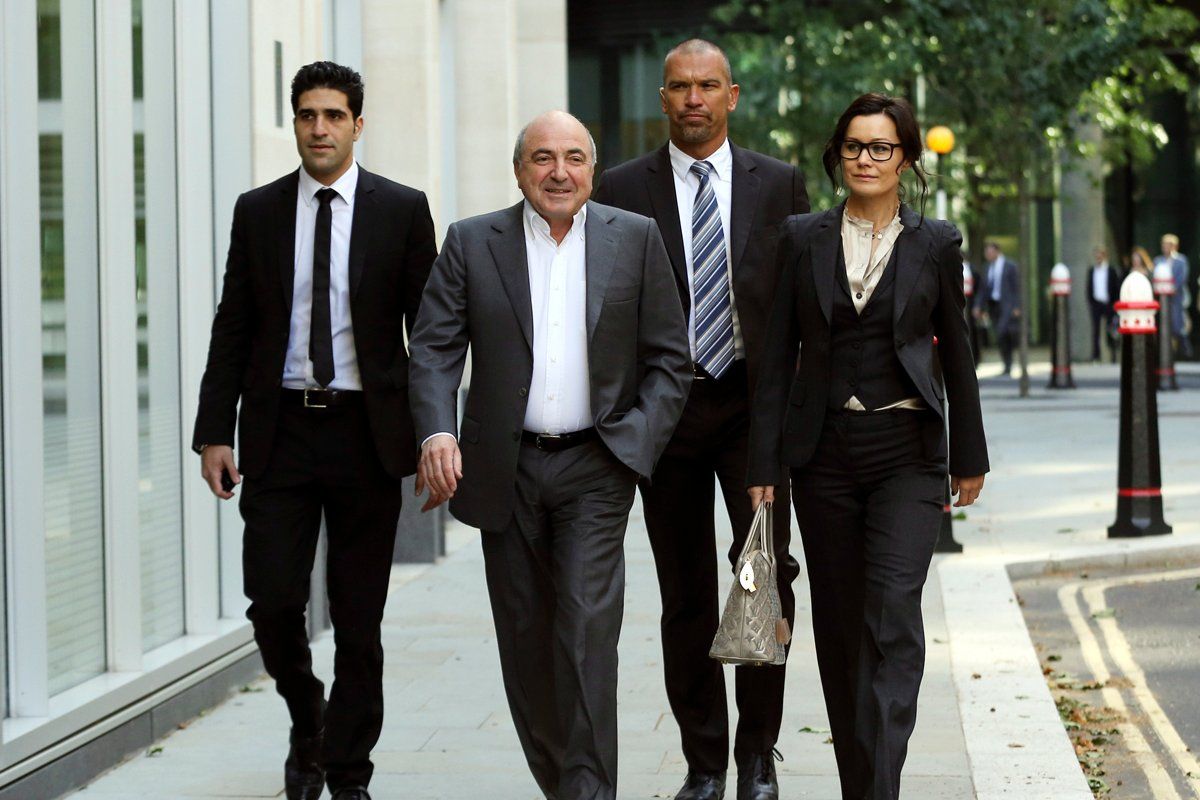

In court, Berezovsky lost, too. Following the most expensive trial in U.K. history, the judge finally ruled in favor of Abramovich on Friday, dismissing Berezovsky's case.

The judge, Elizabeth Gloster, described the oligarch as "inherently unreliable," "I gained the impression he had deluded himself into believing his own version of events," she said.

Within minutes of the ruling, Berezovsky was outside the court, addressing a media scrum, suggesting that "it was as if [President Vladimir] Putin had written the verdict," seemingly at pains to suggest that, while he was momentarily down, he wasn't out for the count.

But the definitive image of the fallen titan remains a photograph of Berezovsky taken earlier in front of the Russian Embassy in London, an estranged, increasingly eccentric dissident holding up a placard with words addressed to the Moth: "I made you, and I will destroy you."

Peter Pomerantsev is a television producer and nonfiction writer. Alexey Kovalev is editor of the news site inosmi.ru.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.